Pavel Vrublevsky, founder of the Russian payment technology firm ChronoPay and the antagonist in my 2014 book “Spam Nation,” was arrested in Moscow this month and charged with fraud. Russian authorities allege Vrublevsky operated several fraudulent SMS-based payment schemes, and facilitated money laundering for Hydra, the largest Russian darknet market. But according to information obtained by KrebsOnSecurity, it is equally likely Vrublevsky was arrested thanks to his propensity for carefully documenting the links between Russia’s state security services and the cybercriminal underground.

An undated photo of Vrublevsky at his ChronoPay office in Moscow.

ChronoPay specializes in providing access to the global credit card networks for “high risk” merchants — businesses involved in selling services online that tend to generate an unusually large number of chargebacks and reports of fraud, and hence have a higher risk of failure.

When I first began writing about Vrublevsky in 2009 as a reporter for The Washington Post, ChronoPay and its sister firm Red & Partners (RNP) were earning millions setting up payment infrastructure for fake antivirus peddlers and spammers pimping male enhancement drugs.

Using the hacker alias “RedEye,” the ChronoPay CEO oversaw a burgeoning pharmacy spam affiliate program called Rx-Promotion, which paid some of Russia’s most talented spammers and virus writers to bombard the world with junk email promoting Rx-Promotion’s pill shops. RedEye also was the administrator of Crutop, a Russian language forum and affiliate program that catered to thousands of adult webmasters.

In 2013, Vrublevsky was sentenced to 2.5 years in a Russian penal colony for convincing one of his top affiliates to launch a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against a competitor that shut down the ticketing system for the state-owned Aeroflot airline.

Following his release from jail, Vrublevsky began working on a new digital payments platform based in Hong Kong called HPay Ltd (a.k.a. Hong Kong Processing Corporation). HPay appears to have had a great number of clients that were running schemes which bamboozled people with fake lotteries and prize contests.

According to Russian prosecutors, the scam went like this: Consumers would receive an SMS with links to sites that falsely claimed a number of well-known companies were sponsoring drawings and lotteries for people who enrolled or agreed to answer surveys. All who responded were told they were winners, but also that they had to pay a commission to pick up the prize. That scheme allegedly stole 500 million rubles (~ USD $4.5 million) from over 100,000 consumers.

There are scant public records that show a connection between ChronoPay and HPay, apart from the fact that the latter’s website — hpay[.]io — was originally hosted on the same server (185.180.196.74) along with a handful of other domains, including Vrublevsky’s personal website rnp[.]com.

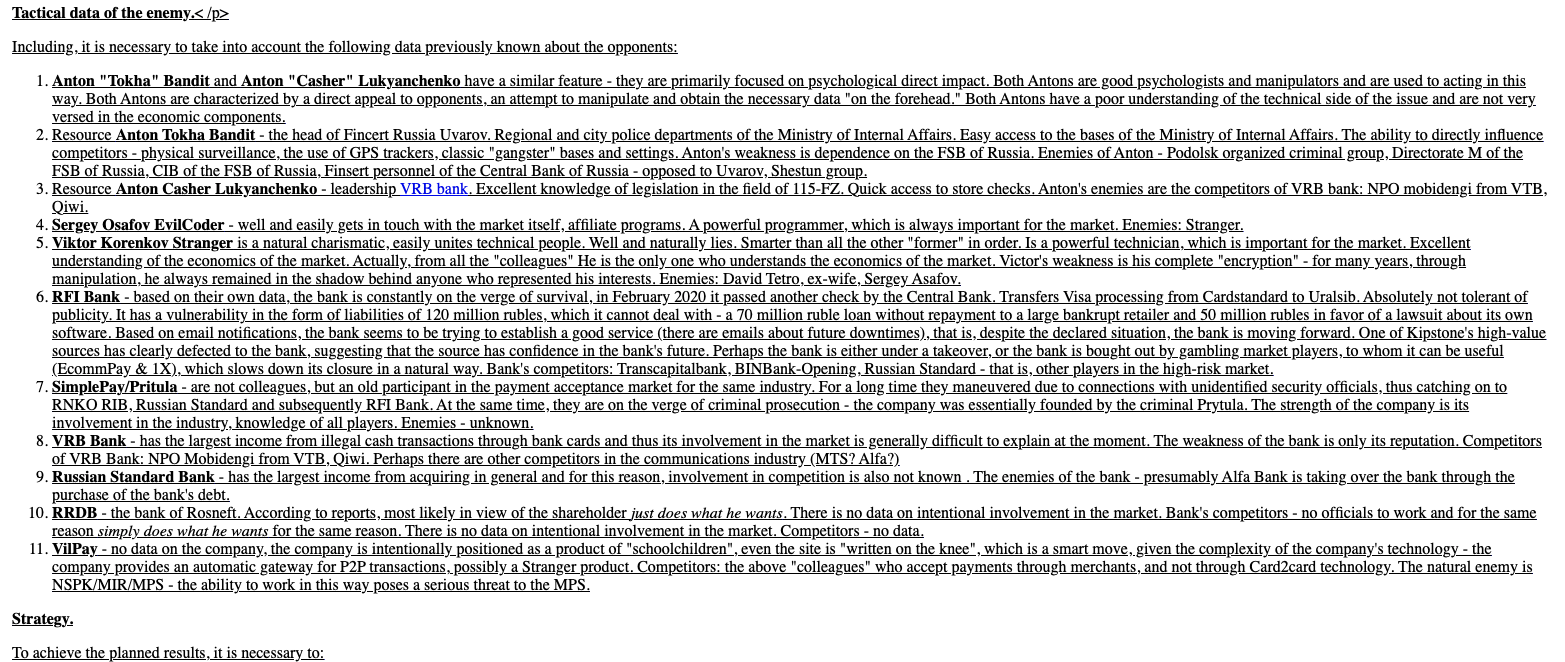

But then earlier this month, KrebsOnSecurity received a large amount of information that was stolen from ChronoPay recently when hackers managed to compromise the company’s Confluence server. Confluence is a web-based corporate wiki platform, and ChronoPay used their Confluence installation to document in exquisite detail how it creatively distributes the risk associated with high-risk processing by routing transactions through a myriad of shell companies and third-party processors.

Incredibly, Vrublevsky himself appears to have used ChronoPay’s Confluence wiki to document his entire 20+ years of personal and professional history in the high-risk payments space, including the company’s most recent forays with HPay. The latest document in the hacked archive is dated April 2021.

These diary entries, interspersed between highly technical how-tos, are all written in Russian and in the third person. But they are unmistakably Vrublevsky’s words: Some of the elaborate stories in the wiki were identical to theories that Vrublevsky himself espoused to me throughout hundreds of hours of phone interviews. Also, in some of the entries the narrator switches from “he” to “I” when describing the actions of Vrublevsky.

Vrublevsky’s memoire/wiki invokes the nicknames and real names of Russian hackers who worked with the protection of corrupt officials in the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the successor agency to the Soviet KGB. In several diary entries, Vrublevsky writes about various cybercriminals and Russian law enforcement officials involved in processing credit card payments tied to online gambling sites.

Russian banks are prohibited from processing payments for online gambling, and as a result many online gaming sites catering to Russian speakers have chosen to process credit card payments through Ukrainian financial institutions.

That’s according to Vladislav “BadB” Horohorin, the convicted cybercriminal who shared the ChronoPay Confluence data with KrebsOnSecurity. In February 2017, Horohorin was released after serving four years in a U.S. prison for his role in the 2009 theft of more than $9 million from RBS Worldpay.

Horohorin said Vrublevsky has been using his knowledge of the card processing networks to extort people in the online gambling industry who may run afoul of Russian laws.

“Russia has strict regulations against processing for the gambling business,” Horohorin said. “While Russian banks can’t do it, Ukrainian ones can, so we have Ukrainian banks processing gambling and casinos, which mostly Russian gamblers use. What Pavel does is he blackmails those Ukrainian banks using his connections and knowledge. Some pay, some don’t. But some people are not very tolerant of that kind of abuse.” Continue reading