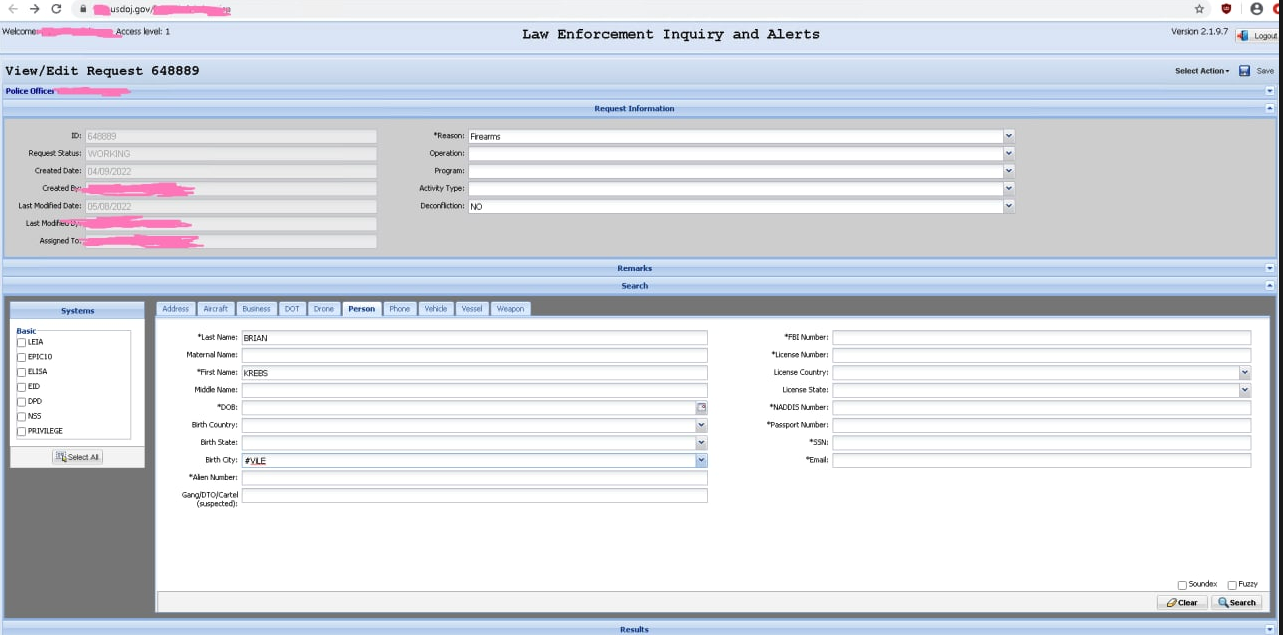

Millions of U.S. government employees and contractors have been issued a secure smart ID card that enables physical access to buildings and controlled spaces, and provides access to government computer networks and systems at the cardholder’s appropriate security level. But many government employees aren’t issued an approved card reader device that lets them use these cards at home or remotely, and so turn to low-cost readers they find online. What could go wrong? Here’s one example.

A sample Common Access Card (CAC). Image: Cac.mil.

KrebsOnSecurity recently heard from a reader — we’ll call him “Mark” because he wasn’t authorized to speak to the press — who works in IT for a major government defense contractor and was issued a Personal Identity Verification (PIV) government smart card designed for civilian employees. Not having a smart card reader at home and lacking any obvious guidance from his co-workers on how to get one, Mark opted to purchase a $15 reader from Amazon that said it was made to handle U.S. government smart cards.

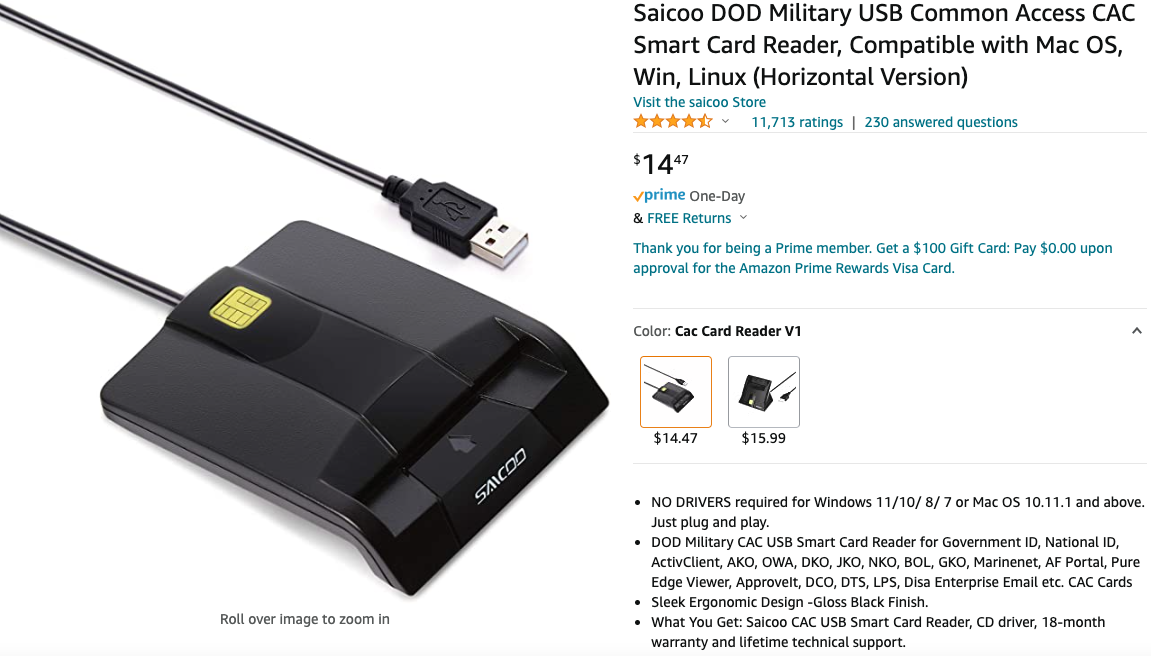

The USB-based device Mark settled on is the first result that currently comes up one when searches on Amazon.com for “PIV card reader.” The card reader Mark bought was sold by a company called Saicoo, whose sponsored Amazon listing advertises a “DOD Military USB Common Access Card (CAC) Reader” and has more than 11,700 mostly positive ratings.

The Common Access Card (CAC) is the standard identification for active duty uniformed service personnel, selected reserve, DoD civilian employees, and eligible contractor personnel. It is the principal card used to enable physical access to buildings and controlled spaces, and provides access to DoD computer networks and systems.

Mark said when he received the reader and plugged it into his Windows 10 PC, the operating system complained that the device’s hardware drivers weren’t functioning properly. Windows suggested consulting the vendor’s website for newer drivers.

The Saicoo smart card reader that Mark purchased. Image: Amazon.com

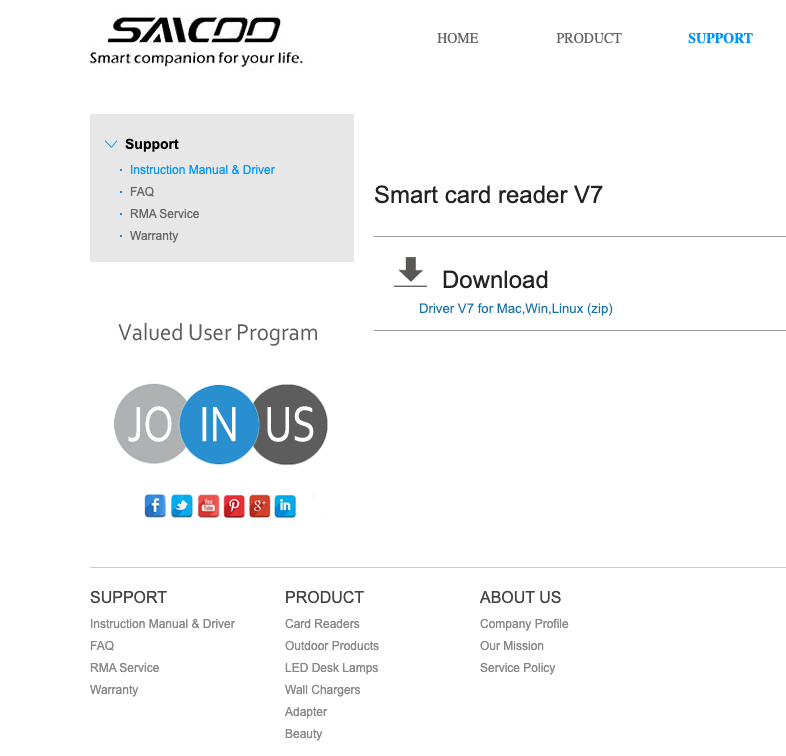

So Mark went to the website mentioned on Saicoo’s packaging and found a ZIP file containing drivers for Linux, Mac OS and Windows:

Image: Saicoo

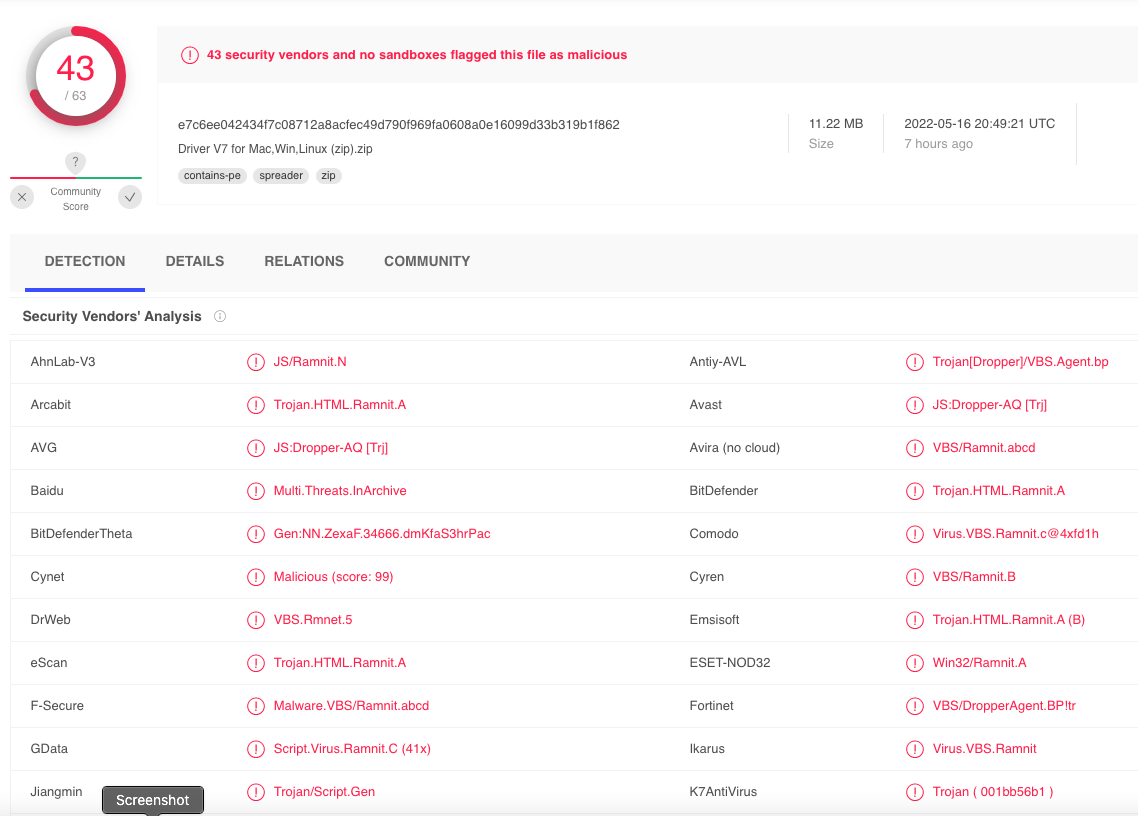

Out of an abundance of caution, Mark submitted Saicoo’s drivers file to Virustotal.com, which simultaneously scans any shared files with more than five dozen antivirus and security products. Virustotal reported that some 43 different security tools detected the Saicoo drivers as malicious. The consensus seems to be that the ZIP file currently harbors a malware threat known as Ramnit, a fairly common but dangerous trojan horse that spreads by appending itself to other files.

Ramnit is a well-known and older threat — first surfacing more than a decade ago — but it has evolved over the years and is still employed in more sophisticated data exfiltration attacks. Amazon said in a written statement that it was investigating the reports.

“Seems like a potentially significant national security risk, considering that many end users might have elevated clearance levels who are using PIV cards for secure access,” Mark said.

Mark said he contacted Saicoo about their website serving up malware, and received a response saying the company’s newest hardware did not require any additional drivers. He said Saicoo did not address his concern that the driver package on its website was bundled with malware.

In response to KrebsOnSecurity’s request for comment, Saicoo sent a somewhat less reassuring reply.

“From the details you offered, issue may probably caused by your computer security defense system as it seems not recognized our rarely used driver & detected it as malicious or a virus,” Saicoo’s support team wrote in an email.

“Actually, it’s not carrying any virus as you can trust us, if you have our reader on hand, please just ignore it and continue the installation steps,” the message continued. “When driver installed, this message will vanish out of sight. Don’t worry.” Continue reading