Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter this week all took steps to crack down on users involved in trafficking hijacked user accounts across their platforms. The coordinated action seized hundreds of accounts the companies say have played a major role in facilitating the trade and often lucrative resale of compromised, highly sought-after usernames.

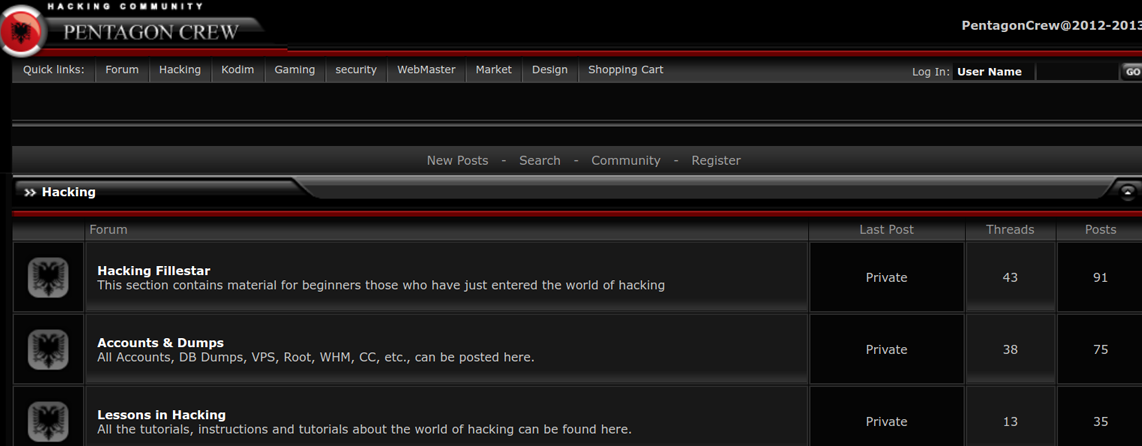

At the center of the account ban wave are some of the most active members of OGUsers, a forum that caters to thousands of people selling access to hijacked social media and other online accounts.

At the center of the account ban wave are some of the most active members of OGUsers, a forum that caters to thousands of people selling access to hijacked social media and other online accounts.

Particularly prized by this community are short usernames, which can often be resold for thousands of dollars to those looking to claim a choice vanity name.

Facebook told KrebsOnSecurity it seized hundreds of accounts — mainly on Instagram — that have been stolen from legitimate users through a variety of intimidation and harassment tactics, including hacking, coercion, extortion, sextortion, SIM swapping, and swatting.

THE MIDDLEMEN

Facebook said it targeted a number of accounts tied to key sellers on OGUsers, as well as those who advertise the ability to broker stolen account sales.

Like most cybercrime forums, OGUsers is overrun with shady characters who are there mainly to rip off other members. As a result, some of the most popular denizens of the community are those who’ve earned a reputation as trusted “middlemen.”

These core members offer escrow services that – in exchange for a cut of the total transaction cost (usually five percent) — will hold the buyer’s funds until he is satisfied that the seller has delivered the credentials and any email account access needed to control the hijacked social media account.

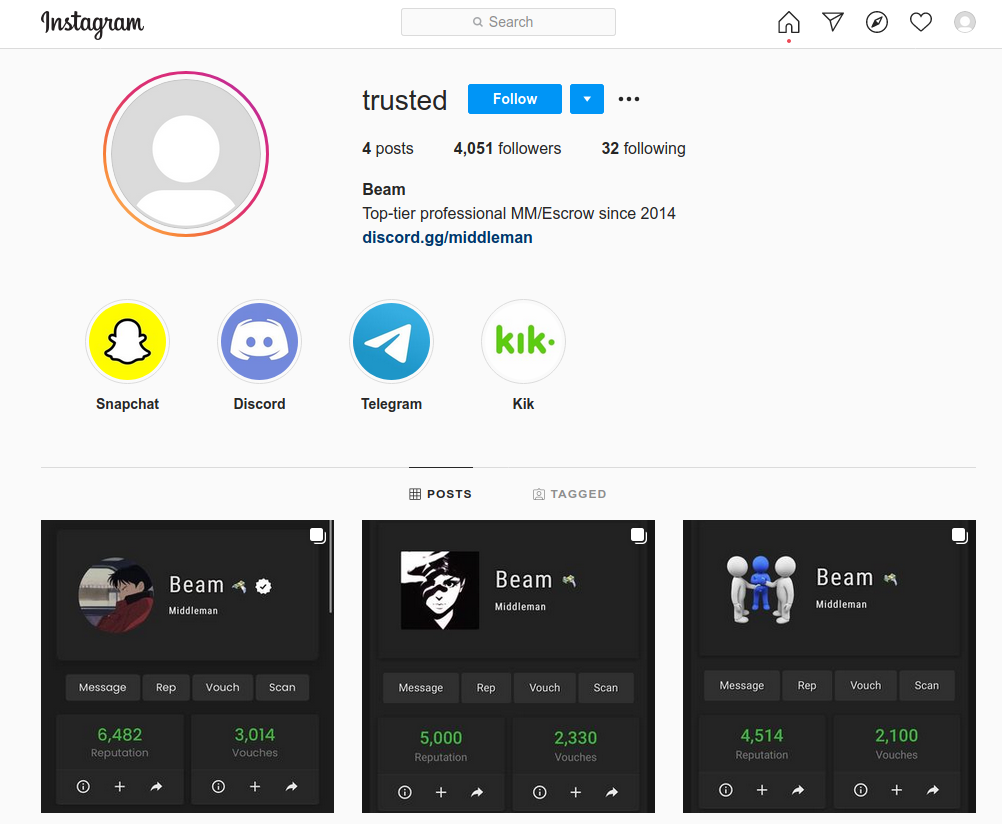

For example, one of the most active accounts targeted in this week’s social network crackdown is the Instagram profile “Trusted,” self-described as “top-tier professional middleman/escrow since 2014.”

Trusted’s profile included several screenshots of his OGUsers persona, “Beam,” who warns members about an uptick in the number of new OGUsers profiles impersonating him and other middlemen on the forum. Beam currently has more reputation points or “vouches” than almost anyone on the forum, save for perhaps the current and former site administrators.

The now-banned Instagram account for the middleman @trusted/beam.

Helpfully, OGUsers has been hacked multiple times over the years, and its database of user details and private messages posted on competing crime forums. Those databases show Beam was just the 12th user account created on OGUsers back in 2014.

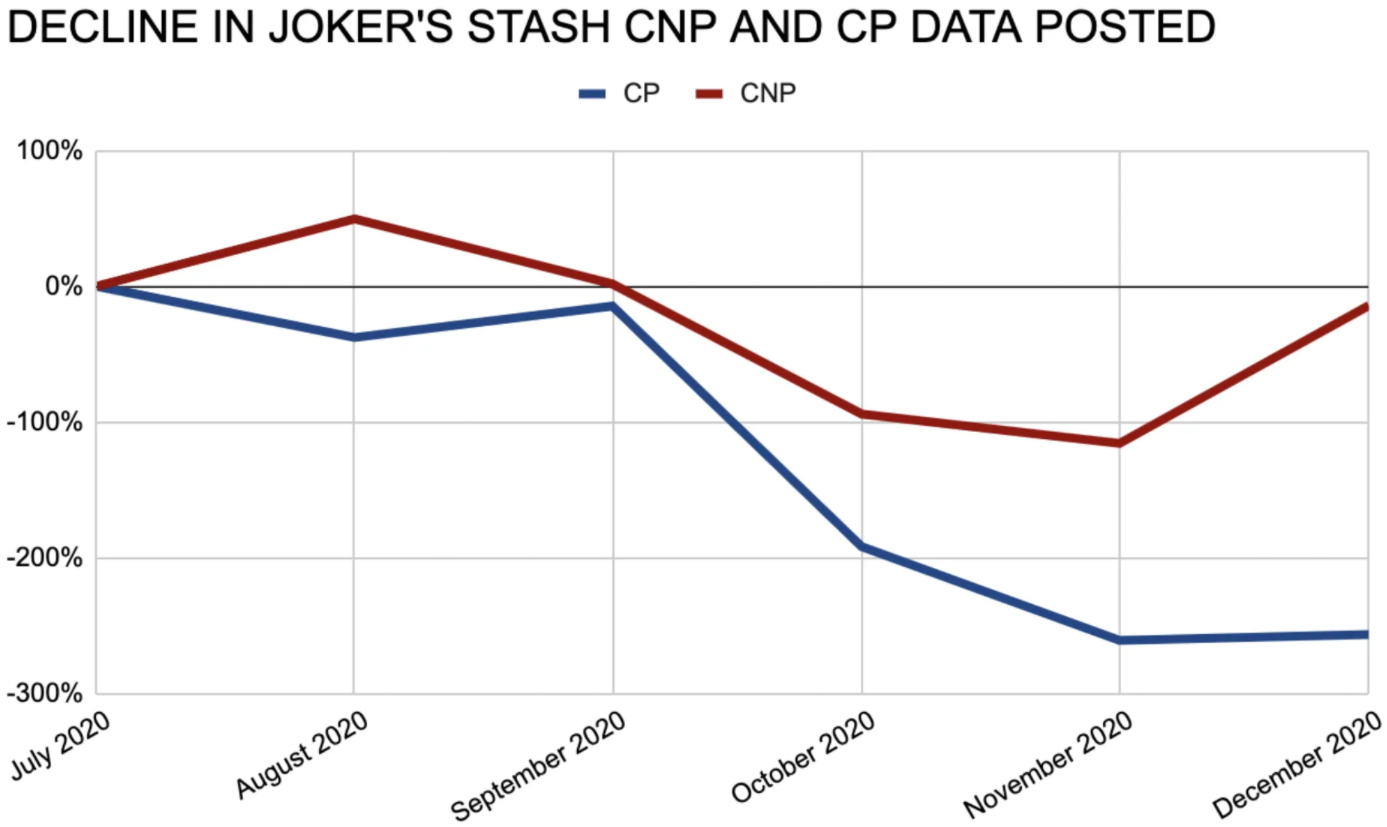

In his posts, Beam says he has brokered well north of 10,000 transactions. Indeed, the leaked OGUsers databases — which include private messages on the forum prior to June 2020 — offer a small window into the overall value of the hijacked social media account industry.

In each of Beam’s direct messages to other members who hired him as a middleman he would include the address of the bitcoin wallet to which the buyer was to send the funds. Just two of the bitcoin wallets Beam used for middlemanning over the past of couple of years recorded in excess of 6,700 transactions totaling more than 243 bitcoins — or roughly $8.5 million by today’s valuation (~$35,000 per coin). Beam would have earned roughly $425,000 in commissions on those sales.

Beam, a Canadian whose real name is Noah Hawkins, declined to be interviewed when contacted earlier this week. But his “Trusted” account on Instagram was taken down by Facebook today, as were “@Killer,” — a personal Instagram account he used under the nickname “noah/beam.” Beam’s Twitter account — @NH — has been deactivated by Twitter; it was hacked and stolen from its original owner back in 2014.

Reached for comment, Twitter confirmed that it worked in tandem with Facebook to seize accounts tied to top members of OGUsers, citing its platform manipulation and spam policy. Twitter said its investigation into the people behind these accounts is ongoing.

TikTok confirmed it also took action to target accounts tied to top OGUusers members, although it declined to say how many accounts were reclaimed.

“As part of our ongoing work to find and stop inauthentic behavior, we recently reclaimed a number of TikTok usernames that were being used for account squatting,” TikTok said in a written statement. “We will continue to focus on staying ahead of the ever-evolving tactics of bad actors, including cooperating with third parties and others in the industry.” Continue reading

One state’s experience offers a window into the potential scope of the problem. Hackers, identity thieves and overseas criminal rings stole over $11 billion in unemployment benefits from California last year, or roughly 10 percent of all such claims the state paid out in 2020, the state’s labor secretary

One state’s experience offers a window into the potential scope of the problem. Hackers, identity thieves and overseas criminal rings stole over $11 billion in unemployment benefits from California last year, or roughly 10 percent of all such claims the state paid out in 2020, the state’s labor secretary