Multiple security firms recently identified cryptocurrency mining service Coinhive as the top malicious threat to Web users, thanks to the tendency for Coinhive’s computer code to be used on hacked Web sites to steal the processing power of its visitors’ devices. This post looks at how Coinhive vaulted to the top of the threat list less than a year after its debut, and explores clues about the possible identities of the individuals behind the service.

Coinhive is a cryptocurrency mining service that relies on a small chunk of computer code designed to be installed on Web sites. The code uses some or all of the computing power of any browser that visits the site in question, enlisting the machine in a bid to mine bits of the Monero cryptocurrency.

Monero differs from Bitcoin in that its transactions are virtually untraceble, and there is no way for an outsider to track Monero transactions between two parties. Naturally, this quality makes Monero an especially appealing choice for cybercriminals.

Coinhive released its mining code last summer, pitching it as a way for Web site owners to earn an income without running intrusive or annoying advertisements. But since then, Coinhive’s code has emerged as the top malware threat tracked by multiple security firms. That’s because much of the time the code is installed on hacked Web sites — without the owner’s knowledge or permission.

Much like a malware infection by a malicious bot or Trojan, Coinhive’s code frequently locks up a user’s browser and drains the device’s battery as it continues to mine Monero for as long a visitor is browsing the site.

According to publicwww.com, a service that indexes the source code of Web sites, there are nearly 32,000 Web sites currently running Coinhive’s JavaScript miner code. It’s impossible to say how many of those sites have installed the code intentionally, but in recent months hackers have secretly stitched it into some extremely high-profile Web sites, including sites for such companies as The Los Angeles Times, mobile device maker Blackberry, Politifact, and Showtime.

And it’s turning up in some unexpected places: In December, Coinhive code was found embedded in all Web pages served by a WiFi hotspot at a Starbucks in Buenos Aires. For roughly a week in January, Coinhive was found hidden inside of YouTube advertisements (via Google’s DoubleClick platform) in select countries, including Japan, France, Taiwan, Italy and Spain. In February, Coinhive was found on “Browsealoud,” a service provided by Texthelp that reads web pages out loud for the visually impaired. The service is widely used on many UK government websites, in addition to a few US and Canadian government sites.

What does Coinhive get out of all this? Coinhive keeps 30 percent of whatever amount of Monero cryptocurrency that is mined using its code, whether or not a Web site has given consent to run it. The code is tied to a special cryptographic key that identifies which user account is to receive the other 70 percent.

Coinhive does accept abuse complaints, but it generally refuses to respond to any complaints that do not come from a hacked Web site’s owner (it mostly ignores abuse complaints lodged by third parties). What’s more, when Coinhive does respond to abuse complaints, it does so by invalidating the key tied to the abuse.

But according to Troy Mursch, a security expert who spends much of his time tracking Coinhive and other instances of “cryptojacking,” killing the key doesn’t do anything to stop Coinhive’s code from continuing to mine Monero on a hacked site. Once a key is invalidated, Mursch said, Coinhive keeps 100 percent of the cryptocurrency mined by sites tied to that account from then on.

Mursch said Coinhive appears to have zero incentive to police the widespread abuse that is leveraging its platform.

“When they ‘terminate’ a key, it just terminates the user on that platform, it doesn’t stop the malicious JavaScript from running, and it just means that particular Coinhive user doesn’t get paid anymore,” Mursch said. “The code keeps running, and Coinhive gets all of it. Maybe they can’t do anything about it, or maybe they don’t want to. But as long as the code is still on the hacked site, it’s still making them money.”

Reached for comment about this apparent conflict of interest, Coinhive replied with a highly technical response, claiming the organization is working on a fix to correct that conflict.

“We have developed Coinhive under the assumption that site keys are immutable,” Coinhive wrote in an email to KrebsOnSecurity. “This is evident by the fact that a site key can not be deleted by a user. This assumption greatly simplified our initial development. We can cache site keys on our WebSocket servers instead of reloading them from the database for every new client. We’re working on a mechanism [to] propagate the invalidation of a key to our WebSocket servers.”

AUTHEDMINE

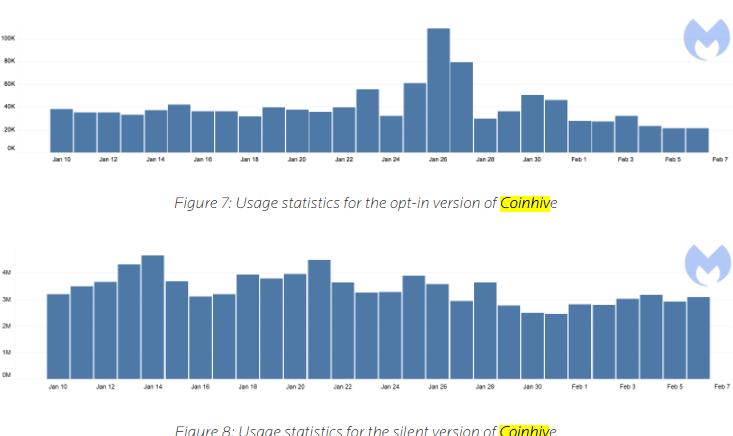

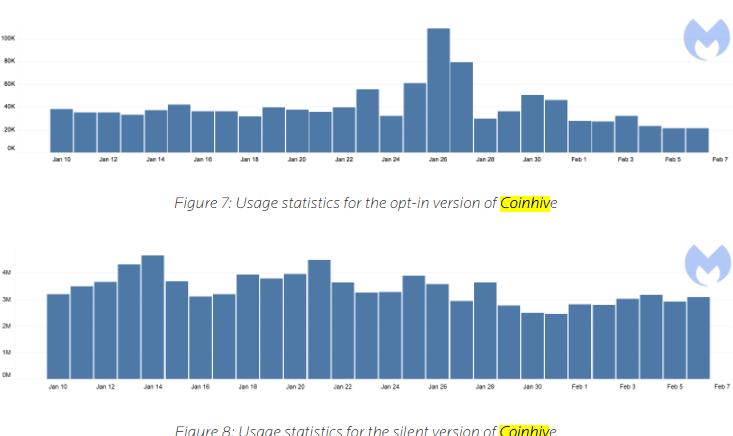

Coinhive has responded to such criticism by releasing a version of their code called “AuthedMine,” which is designed to seek a Web site visitor’s consent before running the Monero mining scripts. Coinhive maintains that approximately 35 percent of the Monero cryptocurrency mining activity that uses its platform comes from sites using AuthedMine.

But according to a report published in February by security firm Malwarebytes, the AuthedMine code is “barely used” compared to the use of Coinhive’s mining code that does not seek permission from Web site visitors. Malwarebytes’ telemetry data (drawn from antivirus alerts when users browse to a site running Coinhive’s code) determined that AuthedMine is used in a little more than one percent of all cases that involve Coinhive’s mining code.

Image: Malwarebytes. The statistic above refer to the number of times per day between Jan. 10 and Feb. 7 that Malwarebytes blocked connections to AuthedMine and Coinhive, respectively.

Asked to comment on the Malwarebytes findings, Coinhive replied that if relatively few people are using AuthedMine it might be because anti-malware companies like Malwarebytes have made it unprofitable for people to do so.

“They identify our opt-in version as a threat and block it,” Coinhive said. “Why would anyone use AuthedMine if it’s blocked just as our original implementation? We don’t think there’s any way that we could have launched Coinhive and not get it blacklisted by Antiviruses. If antiviruses say ‘mining is bad,’ then mining is bad.”

Similarly, data from the aforementioned source code tracking site publicwww.com shows that some 32,000 sites are running the original Coinhive mining script, while the site lists just under 1,200 sites running AuthedMine.

WHO IS COINHIVE?

[Author’s’ note: Ordinarily, I prefer to link to sources of information cited in stories, such as those on Coinhive’s own site and other entities mentioned throughout the rest of this piece. However, because many of these links either go to sites that actively mine with Coinhive or that include decidedly not-safe-for-work content, I have included screenshots instead of links in these cases. For these reasons, I would strongly advise against visiting pr0gramm’s Web site.]

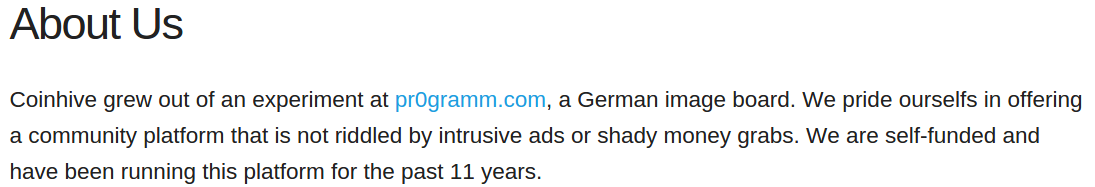

According to a since-deleted statement on the original version of Coinhive’s Web site — coin-hive[dot]com — Coinhive was born out of an experiment on the German-language image hosting and discussion forum pr0gramm[dot]com.

A now-deleted “About us” statement on the original coin-hive[dot]com Web site. This snapshop was taken on Sept. 15, 2017. Image courtesy archive.org.

Indeed, multiple discussion threads on pr0gramm[dot]com show that Coinhive’s code first surfaced there in the third week of July 2017. At the time, the experiment was dubbed “

pr0miner,” and those threads indicate that the core programmer responsible for pr0miner used the nickname “

int13h” on pr0gramm. In a message to this author, Coinhive confirmed that “most of the work back then was done by int13h, who is still on our team.”

I asked Coinhive for clarity on the disappearance of the above statement from its site concerning its affiliation with pr0gramm. Coinhive replied that it had been a convenient fiction:

“The owners of pr0gramm are good friends and we’ve helped them with their infrastructure and various projects in the past. They let us use pr0gramm as a testbed for the miner and also allowed us to use their name to get some more credibility. Launching a new platform is difficult if you don’t have a track record. As we later gained some publicity, this statement was no longer needed.”

Asked for clarification about the “platform” referred to in its statement (“We are self-funded and have been running this platform for the past 11 years”) Coinhive replied, “Sorry for not making it clearer: ‘this platform’ is indeed pr0gramm.”

After receiving this response, it occurred to me that someone might be able to find out who’s running Coinhive by determining the identities of the pr0gramm forum administrators. I reasoned that if they were not one and the same, the pr0gramm admins almost certainly would know the identities of the folks behind Coinhive. Continue reading →

The Microsoft updates affect all supported Windows operating systems, as well as all supported versions of Internet Explorer/Edge, Office, Sharepoint and Exchange Server.

The Microsoft updates affect all supported Windows operating systems, as well as all supported versions of Internet Explorer/Edge, Office, Sharepoint and Exchange Server.