When a retailer’s credit card systems get breached by hackers, banks usually can tell which merchant got hacked soon after those card accounts become available for purchase at underground cybercrime shops. But when companies that collect and sell sensitive consumer data get hacked or are tricked into giving that information to identity thieves, there is no easy way to tell who leaked the data when it ends up for sale in the black market. In this post, we’ll examine one idea to hold consumer data brokers more accountable.

Some of the biggest retail credit card breaches of the past year — including the break-ins at Target and Home Depot — were detected by banks well before news of the incidents went public. When cards stolen from those merchants go up for sale on underground cybercrime shops, the banks often can figure out which merchant got hacked by acquiring a handful of their cards and analyzing the customer purchase history of those accounts. The merchant that is common to all stolen cards across a given transaction period is usually the breached retailer.

Some of the biggest retail credit card breaches of the past year — including the break-ins at Target and Home Depot — were detected by banks well before news of the incidents went public. When cards stolen from those merchants go up for sale on underground cybercrime shops, the banks often can figure out which merchant got hacked by acquiring a handful of their cards and analyzing the customer purchase history of those accounts. The merchant that is common to all stolen cards across a given transaction period is usually the breached retailer.

Sadly, this process of working backwards from stolen data to breach victim generally does not work in the case of breached data brokers that trade in Social Security information and other data, because too often there are no unique markers in the consumer data that would indicate from where the information was obtained.

Even in the handful of cases where underground crime shops selling consumer personal data have included data points in the records they sell that would permit that source analysis, it has taken years’ worth of very imaginative investigation by law enforcement to determine which data brokers were at fault. In Nov. 2011, I wrote about an identity theft service called Superget[dot]info, noting that “each purchasable record contains a two- to three-letter “sourceid,” which may provide clues as to the source of this identity information.”

Unfortunately, the world didn’t learn the source of that ID theft service’s data until 2013, a year after U.S. Secret Service agents arrested the site’s proprietor — a 24-year-old from Vietnam who was posing as a private investigator based in the United States. Only then were investigators able to determine that the source ID data matched information being sold by a subsidiary of big-three credit bureau Experian (among other data brokers that were selling to the ID theft service). But federal agents made that connection only after an elaborate investigation that lured the proprietor of that shop out of Vietnam and into a U.S. territory.

Meanwhile, during the more than six years that this service was in operation, Superget.info attracted more than 1,300 customers who paid at least $1.9 million to look up Social Security numbers, dates of birth, addresses, previous addresses, email addresses and other sensitive information on consumers, much of it used for new account fraud and tax return fraud.

Investigators got a lucky break in determining the source of another ID theft service that was busted up and has since changed its name (more on that in a moment). That service — known as “ssndob[dot]ru” — was the service used by exposed[dot]su, a site that proudly displayed the Social Security, date of birth, address history and other information on dozens of Hollywood celebrities, as well as public officials such as First Lady Michelle Obama, then FBI Director Robert Mueller, and CIA Director John Brennan.

As I explained in a 2013 exclusive, civilian fraud investigators working with law enforcement gained access to the back-end server that was being used to handle customer requests for consumer information. That database showed that the site’s 1,300 customers had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars looking up SSNs, birthdays, drivers license records, and obtaining unauthorized credit and background reports on more than four million Americans.

Although four million consumer records may seem like a big number, that figure did not represent the total number of consumer records available through ssndob[dot]ru. Rather, four million was merely the number of consumer records that the service’s customers had paid the service to look up. In short, it appeared that the ID theft service was drawing on active customer accounts inside of major consumer data brokers.

Investigators working on that case later determined that the same crooks who were running ssndob[dot]ru also were operating a small, custom botnet of hacked computers inside of several major data brokers, including LexisNexis, Dun & Bradstreet, and Kroll. All three companies acknowledged infections from the botnet, but shared little else about the incidents.

Despite their apparent role in facilitating (albeit unknowingly) these ID theft services, to my knowledge the data brokers involved have never been held publicly accountable in any court of law or by Congress.

CURRENT ID THEFT SERVICES

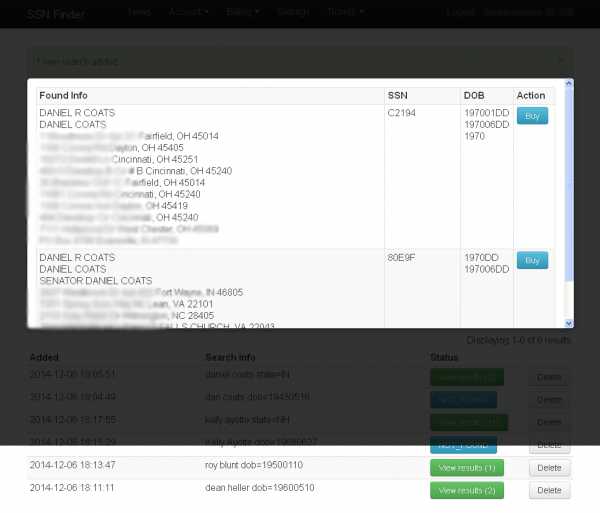

At present, there are multiple shops in the cybercrime underground that sell everything one would need to steal someone’s identity in the United States or apply for new lines of credit in their name — including Social Security numbers, addresses, previous addresses, phone numbers, dates of birth, and in some cases full credit history. The price of this information is shockingly low — about $3 to $5 per record.

KrebsOnSecurity conducted an exhaustive review of consumer data on sale at some of the most popular underground cybercrime sites. The results show that personal information on some of the most powerful Americans remains available for just a few dollars. And of course, if one can purchase this information on these folks, one can buy it on just about anyone in the United States today.

As an experiment, this author checked two of the most popular ID theft services in the underground for the availability of Social Security numbers, phone numbers, addresses and previous addresses on all members of the Senate Commerce Committee‘s Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety and Insurance. That data is currently on sale for all thirteen Democrat and Republican lawmakers on the panel.

Between these two ID theft services, the same personal information was for sale on Edith Ramirez and Richard Cordray, the heads of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), respectively.

Getting these ID theft service Web sites shut down might feel good, but it is not a long-term solution. Both services used to conduct these lookups of the public figures mentioned above are second- and third-generation shops that have re-emerged from previous takedown efforts. In fact, at least one of them appears to be a reincarnation of ssndob[dot]ru, while the other seems little more than a reseller of that service.

Rather, it seems clear that what we need is more active oversight of the data broker industry, and new tools to help law enforcement (and independent investigators) determine the source of data being resold by these identity theft services.

Specifically, if there were a way for federal investigators to add “breach canaries” — unique, dummy identities — to records maintained by the top data brokers, it could make it far easier to tell which broker is leaking consumer data either through breaches or hacked/fraudulent accounts.

Data brokers like Experian have strongly resisted calls from regulators for greater transparency in their operations and in the data that they hold about consumers. When the FTC recommended the creation of a central website where data brokers would be listed — with links to these companies, their privacy policies and also choice options, giving consumers the capability to review/amend the data that companies maintain — Experian lobbied against the idea, charging that it would “have the unintended effect of confusing consumers and eroding trust in e-commerce.”

The company’s main sticking point was essentially that it was unfair to impose such requirements on the bigger data brokers and ignore the rest. Experian’s chief lobbyist Tony Hadley has made the argument that there are just too many companies that have and share all this consumer data, which seems precisely the problem.

“The Direct Marketing Association (DMA) estimates that even a narrow definition of a marketing information service provider is likely to include more than 2,500 companies from all sectors of the economy,” Hadley wrote in a blog post earlier this year. “Simply put, the entire data industry – extremely vital to the US economy — cannot be neatly or accurately identified and then subjected to unrealistic requirements.”

My guess is that if the data broker giants are opposed to the idea of inserting dummy identities into their records to act as breach canaries, it is because such a practice could expose data-sharing relationships and record-keeping practices that these companies would rather not see the light of day. But barring any creative ideas to help investigators quickly learn the source of data being sold by identity theft services online, data brokers will remain free to facilitate and even profit from an illicit market for sensitive consumer information.

One reason you can’t get the politicians to regulate the data brokers is because politicians are major users of the data. Political parties and political groups are among the largest users and customers of data brokers, not just in buying mailing lists but knowing who in any region is voting for whom. Major major databases exist for every congressional district, detailing party affiliation and past voting records for every voting age human in the district. People who are independent or people who are regular voters are all logged, and they know who you voted for, based on your income and demographics. All this info is sold and resold during the campaign season, and is a major reason no politician will regulate this industry.

Information sharing by credit bureaus and data brokers has gone so fare off the reservation. Whatever they think people are consenting to if they haven’t mailed in 15 different opt out forms, this isn’t it. That aside the current reliance on pseudo significant information to authenticate a person’s identity is absurd. Anyone over 30 probably can’t even guess how many companies and individuals could know their social security number. Your driver’s license number and your bank account number aren’t secrets either, the later is written at the bottom of every check you write. We need systems that identify people not by info that is semi-hard to know, but by something completely unknowable.