Popular file-sharing site Mega.nz is warning users that cybercriminals hacked its browser extension for Google Chrome so that usernames and passwords submitted through the browser were copied and forwarded to a rogue server in Ukraine. This attack serves as a fresh reminder that legitimate browser extensions can and periodically do fall into the wrong hands, and that it makes good security sense to limit your exposure to such attacks by getting rid of extensions that are no longer useful or actively maintained by developers.

In a statement posted to its Web site, Mega.nz said the extension for Chrome was compromised after its Chrome Web store account was hacked. From their post:

“On 4 September 2018 at 14:30 UTC, an unknown attacker uploaded a trojaned version of MEGA’s Chrome extension, version 3.39.4, to the Google Chrome webstore. Upon installation or autoupdate, it would ask for elevated permissions (Read and change all your data on the websites you visit) that MEGA’s real extension does not require and would (if permissions were granted) exfiltrate credentials for sites including amazon.com, live.com, github.com, google.com (for webstore login), myetherwallet.com, mymonero.com, idex.market and HTTP POST requests to other sites, to a server located in Ukraine. Note that mega.nz credentials were not being exfiltrated.”

Browser extensions can be incredibly handy and useful, but compromised extensions — depending on the level of “permissions” or access originally granted to them — also can give attackers access to all data on your computer and the Web sites you visit.

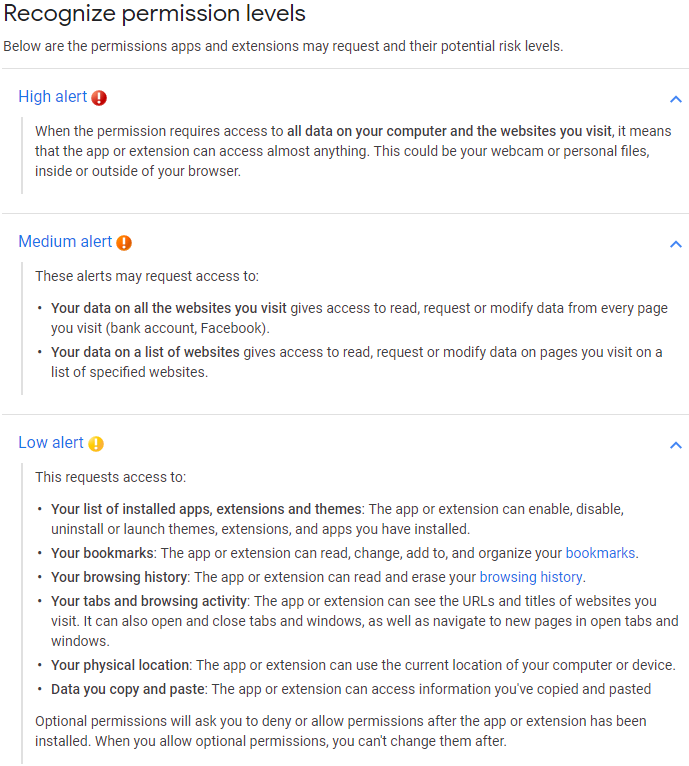

For its part, Google tries to communicate the potential risk of extensions using three “alert” levels: Low, medium and high, as detailed in the screenshot below. In practice, however, most extensions carry the medium or high alert level, which means that if the extension is somehow compromised (or malicious from the get-go), the attacker in control of it is going to have access to ton of sensitive information on a great many Internet users.

In many instances — as in this week’s breach with Mega — an extension gets compromised after someone with legitimate rights to alter its code gets phished or hacked. In other cases, control and ownership of an established extension may simply be abandoned or sold to shady developers. In either scenario, hacked or backdoored extensions can present a nightmare for users.

A basic tenet of cybersecurity holds that individuals and organizations can mitigate the risk of getting hacked to some degree by reducing their overall “attack surface” — i.e., the amount of software and services they rely upon that are potentially vulnerable to compromise. That precept holds fast here as well, because limiting one’s reliance on third-party browser extensions reduces one’s risk significantly.

Personally, I do not make much use of browser extensions. In almost every case I’ve considered installing an extension I’ve been sufficiently spooked by the permissions requested that I ultimately decided it wasn’t worth the risk. I currently trust just three extensions in my Google Chrome installation; two of them are made by Google and carry “low” risk alert levels. The other is a third-party extension I’ve used for years that carries a “medium” risk rating, but that is also maintained by an individual I know who is extremely paranoid and security-conscious.

If you’re the type of person who uses multiple extensions, it may be wise to adopt a risk-based approach going forward. In other words, given the high stakes that typically come with installing an extension, consider carefully whether having a given extension is truly worth it. By the way, this applies equally to plug-ins designed for Web site content management systems like WordPress and Joomla.

At the very least, do not agree to update an extension if it suddenly requests more permissions than a previous version. This should be a giant red flag that something is not right.

Also, never download and install an extension just because a Web site says you need it to view some type of content. Doing otherwise is almost always a high-risk proposition. Here, Rule #1 from KrebsOnSecurity’s Three Rules of Online Safety comes into play: “If you didn’t go looking for it, don’t install it.” Finally, in the event you do wish to install something, make sure you’re getting it directly from the entity that produced the software.

Google Chrome users can see any extensions they have installed by clicking the three dots to the right of the address bar, selecting “More tools” in the resulting drop-down menu, then “Extensions.” In Firefox, click the three horizontal bars next to the address bar and select “Add-ons,” then click the “Extensions” link on the resulting page to view any installed extensions.

It is funny that everyone got mad at Microsoft Edge because it did not allow extensions. Now it does. Now we recognize what Microsoft was right in omitting extensions. Extensions are not to be trusted.

What is even more bothersome to me is the amount of shared JavaScript out there. Web pages all pulling the shared script from content delivery networks. If the source script were to be compromised, all of the web pages that use it will instantly be compromised.

I checked my bank’s web site to see if they only pull script from within their domain. They don’t. They also pull in an analytics package from a shared source. Yikes!

How would I determine that for my bank? And … do perhaps all or most American banks do that?

Yeah, install uMatrix(better) or NoScript(simpler) addon. uMatrix lists all the other domains. Requests Policy is even better.

Great in theory. But maybe not in practice—unless someone wants to build a browser with all the various features/tricks some people have come to expect in a modern browser, and not have it been a huge burden on your system. Even though I’m in IT and know I probably shouldn’t install extensions, there are a few I cannot live without. Then again, I’m constantly checking on what’s going on with them—not something my clients are likely to do.

“I checked my bank’s web site to see if they only pull script from within their domain. They don’t. They also pull in an analytics package from a shared source. Yikes!”

And with the appropriate browser plugins, those scripts can be blocked from loading and running.

I do not make much use of browser extensions. In almost every case I’ve considered installing an extension as they are asking for so much permission.

I do use browser extensions, but only those that serve a security or privacy function such ad blockers, script blockers, and tracker blockers – and I always read the reviews and search online for complaints. I agree that these still create risk as the developer turn control of the extension over to an unscrupulous individual or an update could be malicious, but that’s true for any software. Just look at what happened with CCleaner.

I always enjoy reading your blogs…keep up the good work!

What are your thoughts on the HTTP Everywhere extension, is it legit?