Most of the civilized world years ago shifted to requiring computer chips in payment cards that make it far more expensive and difficult for thieves to clone and use them for fraud. One notable exception is the United States, which is still lurching toward this goal. Here’s a look at the havoc that lag has wrought, as seen through the purchasing patterns at one of the underground’s biggest stolen card shops that was hacked last year.

In October 2019, someone hacked BriansClub, a popular stolen card bazaar that uses this author’s likeness and name in its marketing. Whoever compromised the shop siphoned data on millions of card accounts that were acquired over four years through various illicit means from legitimate, hacked businesses around the globe — but mostly from U.S. merchants. That database was leaked to KrebsOnSecurity, which in turn shared it with multiple sources that help fight payment card fraud.

An ad for BriansClub has been using my name and likeness for years to peddle millions of stolen credit cards.

Among the recipients was Damon McCoy, an associate professor at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering [full disclosure: NYU has been a longtime advertiser on this blog]. McCoy’s work in probing the credit card systems used by some of the world’s biggest purveyors of junk email greatly enriched the data that informed my 2014 book Spam Nation, and I wanted to make sure he and his colleagues had a crack at the BriansClub data as well.

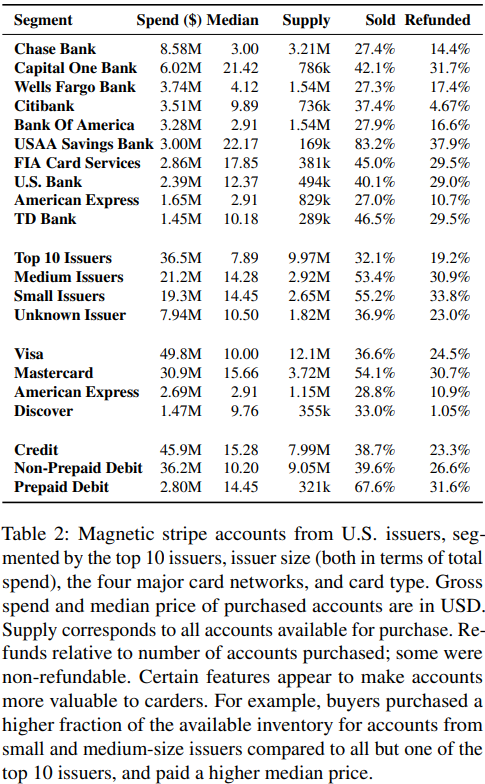

McCoy and fellow NYU researchers found BriansClub earned close to $104 million in gross revenue from 2015 to early 2019, and listed over 19 million unique card numbers for sale. Around 97% of the inventory was stolen magnetic stripe data, commonly used to produce counterfeit cards for in-person payments.

“What surprised me most was there are still a lot of people swiping their cards for transactions here,” McCoy said.

In 2015, the major credit card associations instituted new rules that made it riskier and potentially more expensive for U.S. merchants to continue allowing customers to swipe the stripe instead of dip the chip. Complicating this transition was the fact that many card-issuing U.S. banks took years to replace their customer card stocks with chip-enabled cards, and countless retailers dragged their feet in updating their payment terminals to accept chip-based cards.

Indeed, three years later the U.S. Federal Reserve estimated (PDF) that 43.3 percent of in-person card payments were still being processed by reading the magnetic stripe instead of the chip. This might not have been such a big deal if payment terminals at many of those merchants weren’t also compromised with malicious software that copied the data when customers swiped their cards.

Following the 2015 liability shift, more than 84 percent of the non-chip cards advertised by BriansClub were sold, versus just 35 percent of chip-based cards during the same time period.

“All cards without a chip were in much higher demand,” McCoy said.

Perhaps surprisingly, McCoy and his fellow NYU researchers found BriansClub customers purchased only 40% of its overall inventory. But what they did buy supports the notion that crooks generally gravitate toward cards issued by financial institutions that are perceived as having fewer or more lax protections against fraud.

While the top 10 largest card issuers in the United States accounted for nearly half of the accounts put up for sale at BriansClub, only 32 percent of those accounts were sold — and at a roughly half the median price of those issued by small- and medium-sized institutions.

In contrast, more than half of the stolen cards issued by small and medium-sized institutions were purchased from the fraud shop. This was true even though by the end of 2018, 91 percent of cards for sale from medium-sized institutions were chip-based, and 89 percent from smaller banks and credit unions. Nearly all cards issued by the top ten largest U.S. card issuers (98 percent) were chip-enabled by that time.

REGION LOCK

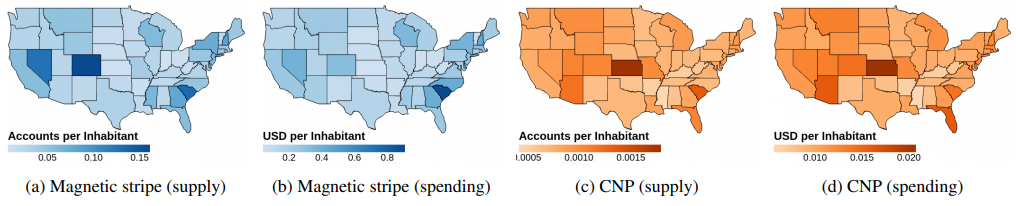

The researchers found BriansClub customers strongly preferred cards issued by financial institutions in specific regions of the United States, specifically Colorado, Nevada, and South Carolina.

“For whatever reason, those regions were perceived as having lower anti-fraud systems or those that were not as effective,” McCoy said.

Cards compromised from merchants in South Carolina were in especially high demand, with fraudsters willing to spend twice as much on those cards per capita than any other state — roughly $1 per resident.

That sales trend also was reflected in the support tickets filed by BriansClub customers, who frequently were informed that cards tied to the southeastern United States were less likely to be restricted for use outside of the region.

McCoy said the lack of region locking also made stolen cards issued by banks in China something of a hot commodity, even though these cards demanded much higher prices (often more than $100 per account): The NYU researchers found virtually all available Chinese cards were sold soon after they were put up for sale. Ditto for the relatively few corporate and business cards for sale.

A lack of region locks may also have caused card thieves to gravitate toward buying up as many cards as they could from USAA, a savings bank that caters to active and former military service members and their immediate families. More than 83 percent of the available USAA cards were sold between 2015 and 2019, the researchers found.

Although Visa cards made up more than half of accounts put up for sale (12.1 million), just 36 percent were sold. MasterCards were the second most-plentiful (3.72 million), and yet more than 54 percent of them sold.

American Express and Discover, which unlike Visa and MasterCard are so-called “closed loop” networks that do not rely on third-party financial institutions to issue cards and manage fraud on them, saw 28.8 percent and 33 percent of their stolen cards purchased, respectively.

PREPAIDS

Some people concerned about the scourge of debit and credit card fraud opt to purchase prepaid cards, which generally enjoy the same cardholder protections against fraudulent transactions. But the NYU team found compromised prepaid accounts were purchased at a far higher rate than regular debit and credit cards.

Several factors may be at play here. For starters, relatively few prepaid cards for sale were chip-based. McCoy said there was some data to suggest many of these prepaids were issued to people collecting government benefits such as unemployment and food assistance. Specifically, the “service code” information associated with these prepaid cards indicated that many were restricted for use at places like liquor stores and casinos.

“This was a pretty sad finding, because if you don’t have a bank this is probably how you get your wages,” McCoy said. “These cards were disproportionately targeted. The unfortunate and striking thing was the sheer demand and lack of [chip] support for prepaid cards. Also, these cards were likely more attractive to fraudsters because [the issuer’s] anti-fraud countermeasures weren’t up to par, possibly because they know less about their customers and their typical purchase history.”

PROFITS

The NYU researchers estimate BriansClub pulled in approximately $24 million in profit over four years. They calculated this number by taking the more than $100 million in total sales and subtracting commissions paid to card thieves who supplied the shop with fresh goods, as well as the price of cards that were refunded to buyers. BriansClub, like many other stolen card shops, offers refunds on certain purchases if the buyer can demonstrate the cards were no longer active at the time of purchase.

On average, BriansClub paid suppliers commissions ranging from 50-60 percent of the total value of the cards sold. Card-not-present (CNP) accounts — or those stolen from online retailers and purchased by fraudsters principally for use in defrauding other online merchants — fetched a much steeper supplier commission of 80 percent, but mainly because these cards were in such high demand and low supply.

The NYU team found card-not-present sales accounted for just 7 percent of all revenue, even though card thieves clearly now have much higher incentives to target online merchants.

A story here last year observed that this exact supply and demand tug-of-war had helped to significantly increase prices for card-not-present accounts across multiple stolen credit card shops in the underground. Not long ago, the price of CNP accounts was less than half that of card-present accounts. These days, those prices are roughly equivalent.

One likely reason for that shift is the United States is the last of the G20 nations to fully transition to more secure chip-based payment cards. In every other country that long ago made the chip card transition, they saw the same dynamic: As they made it harder for thieves to counterfeit physical cards, the fraud didn’t go away but instead shifted to online merchants.

The same progression is happening now in the United States, only the demand for stolen CNP data still far outstrips supply. Which might explain why we’ve seen such a huge uptick over the past few years in e-commerce sites getting hacked.

“Everyone points to this displacement effect from card-present to card-not-present fraud,” McCoy said. “But if the supply isn’t there, there’s only so much room for that displacement to occur.”

No doubt the epidemic of card fraud has benefited mightily from hacked retail chains — particularly restaurants — that still allow customers to swipe chip-based cards. But as we’ll see in a post to be published tomorrow, new research suggests thieves are starting to deploy ingenious methods for converting card data from certain compromised chip-based transactions into physical counterfeit cards.

A copy of the NYU research paper is available here (PDF).

Excellent. Thank you!

excellent! Didn’t know that the swipe was dangerous

Nice cliffhanger at the end there, Brian.

Great info! I’m curious…if only the magnetic strip is damaged (demagnetized) on a chip card, does that render the chip useless?

The magstripe is independent of the chip. In a chip-reader, if your magstripe is broken, the chip-card will still function. It just won’t function as a “swipe”.

Similarly, if the chip is defective, you can still use the magstripe if the terminal allows it. Some fraudsters know this and purposefully damage the chip — many terminals will allow you to use the magstripe only after the chip fails a certain number of times.

The first store terminal I went to after my chip apparently got damaged, not only refused the sale, but the bank destroyed the card right in front of me after I reported the problem! They get serious on this Chip-N-Pin card present business! I have to admit, the card looked pretty ragged when I looked at it, but it didn’t seem like I had it that long. We were only now getting the terminals and cards in this area. Apparently the terminal reported a fraud transaction, and not the fact that it was just damage that caused the problem. The bank teller said once that happens, they destroy them if they get a chance. Don’t know if this is a rule or what.

Self-service checkouts are also a good opportunity here – you can stick your non-chip library or public transport card in the chip reader, let it fail the required number of times, then swipe a stolen card and watch the transaction go through with no verification

Thanks, Brian!

Makes me wonder:

Is it worth it to run a salvaged hard drive magnet over the stripes on my cards?

This could backfire on you if any given merchant that you use has a broken chip reader. If you degauss your magstrip, make sure you carry enough cash or other backup payment resource for handling all payments, if the chip on your primary card cannot be read.

Is using the apple pay process anymore or less secure than using the physical card/chip?

Published research indicates that Apple/Android/Google Pay mechanisms are more secure than using a physical card. Of course you aren’t going to hand your phone to a server at a restaurant for payment. If you somehow did, you might be surprised how generous your tip was….

What about Apple Pay vs. tap cards? Which is more secure?

While there are attacks against CHIP, Contactless, and Mobile contactless, they generally don’t scale well. Attacks like ProximityRelay can work for Mobile/Contactless (basically getting “closer” to the card/mobile then the real terminal, and relaying it to another terminal), but are far from cost effective and next to impossible to pull off. Card tokenization also makes even a success it useful for a single TRX.

There have been quite a few attacks against CHIP and SIG, most related to the terminal and card interface spec. CHIP+SIG is the clown school of security, and mostly used because the CHIP+PIN rollout dosnt have uptake.

It should be noted that while OEM Pays while quite secure in implication, do have issues. Instead of cloning plastic, fraud has turned to attacking the mobile provisioning. Attacking Onlinebanking credentials, then using them to get the Issuer to just provision a card to a new phone. What’s worse…those same credentials can be used for things like Online Money Transfers….

Fun fact, in England where CHIP+PIN really put a big dent in criminal acts, there was an uptick in Violent Crime….Seems it’s just as easy to put a knife to someone and walk them to an ATM….a cautionary tale.

Generally though, at the POS/Terminal, CHIP+PIN, or MobileContactless are quite safe and make the type of clone fraud a cost prohibitive venture for the criminally minded.

Actually, in some places they have a payment POS which they bring to the table to have the customer tap and pay.

Yep, some places like the rest of the civilized world

In almost the entire world except the USA, if card payments are accepted, the terminal is brought to the table and the card (or mobile phone) does not have to leave the customer’s sight.

Great article Brian !

What about “Tap-to-Pay”? I never liked this but don’t know how to defeat it.

Excellent question, been wondering that myself.

My understanding: NFC-enabled cards (near-field communication) function only when they’re *very* close to readers — one to two inches maximum — hence, the notional security risks associated with NFC-enabled fones aren’t relevant. Or, addressing the same issue from a different direction, so long as my tin-foil hat is snug, there’s low risk associated with NFC-equipped cards. Unknown to me but knowable: contrast / compare the security of using a card’s chip with its NFC capability.

Arbee, the security of NFC transactions, varies from okay to terrible depending on the bank. Intercepting NFC transactions depends significantly on the size of the antenna used to intercept the communications.

Thanks for your reply.

My understanding is that NFC-enabled cards (distinct from e.g., a smart-fone) have very limited range, max 2 inches / 50 mm. And it’s the presence of a NFC-enabled card that initiates a transaction, not a reader. So the size of a reader’s notional antenna shouldn’t negatively impact the security of a NFC-enabled card.

Contrasting — because a smart-fone’s range is greater (it’s powered, not passive), a higher-gain antenna attached to a reader could increase that mode’s operating range. But near-field transactions relying on smart-fones (e.g. Android / Apple / Google Pay) are all reportedly better-encrypted than near-field card transactions.

My question (and the others in this mini-thread) remains — which is more secure: a physical reader reading a card’s chip, or reliance on a card’s NFC capability?

In Northern California, all the vendors I use have chip readers, all but ONE!!! Gas Stations. In contrast to all the other vendors using chip readers, I know of ONLY ONE gas station, and I drive quite a few miles to use it, that uses chip readers. All the others I know of still use swiping of magnetic strips. Last May, I was still using one card at a local gas station that still has mag strip swipe readers and for the first time in 40 years of credit card use, I got my information stolen and a bad charge showed up. The credit card company reversed that charge and I got a new card but I’ve NEVER used credit cards at that gas station since. I was going in and paying cash before COVID-19. Now, I don’t go there at all but instead drive 20 miles to use this one station that has a chip reader setup. Since magnetic strip reader information is easier to steal and use, it would seem reasonable that bad guys are now focusing on the gas stations, the one remaining strong hold of mag strip readers for credit cards.

With all of this fraud, why are the credit card companies not in a hurry to move to the chip and PIN? Why are they not charging more for swiped transactions to encourage retailers to modernize. What is the current time line for improving credit card security? I thought there was just a couple year grace period, but it seems to be much longer than that.

Because retailers are cheap. It’s taken years for them just to implement chip-and-signature, which is still isn’t as secure as the chip-and-pin used in the rest of the world.

Sure there’s a cost to getting hacked (outright monetary loss, reputational damage, expenses to recover etc) but there’s also a cost of implementing new pinpads and security in the first place. If the first cost is less than the 2nd then guess which one they’re going with?

According to the Visa page at finance.yahoo.com, Visa made $12B profit on $22B revenue in 2019.

According to Catherine Traffis in “Credit Card Processing Fees: A Guide for Small Business Owners’, A small business will pay maybe d10-20 cents per transaction, or 2-3%, or $100/month, plus a $15 fee for receiving a statement.

So, if you’re selling $100 scarves in Berkeley, it would be cheap to complain. But, if you’re selling single doughnuts and coffee in my town, a chip reader might seem extravagant.

There have been many occasions when I attempt to pay with my chip-enabled debit card at a supermarket (different markets), but the chip reader malfunctions, forcing me to use the mag-stripe swipe instead. Retail should do a better job of keeping their chip readers maintained.

I have been issued three new cards in the last couple of months because the bank says my card has been compromised. Card #2 had a $5000 fraud charge!

This all started with a new TAP to pay chip feature.

The fraud department will not share all the details they know so I am at a loss to know how to stop the problem except not use the card for any transactions. I wish there were chip communicators that I could place my card in and the online web site would be able to use the web connection to securely complete the transaction using the card chip..

Went to Home Depot and had a swipe my credit card. Unfortunate to see big box stores still having swipe readers around.

In answer to Scott’s question, yes, Apple Pay is more secure as your transaction doesn’t contain identifiable information regarding you or your card number. From Apple’s FAQ…

“After you authenticate your transaction, the Secure Element provides your Device Account Number and a transaction-specific dynamic security code to the shop’s point of sale terminal along with additional information needed to complete the transaction. Again, neither Apple nor your device sends your actual payment card number. Before they approve the payment, your bank, card issuer or payment network can verify your payment information by checking the dynamic security code to make sure that it’s unique and tied to your device.”

The state of Michigan sure looks a lot different than the way I remember it.

Not surprised to see FIA & US Bank listed though.

Still not uncommon for a store’s chip reader to malfunction and the customer has to swipe anyway. I often wonder if scammers somehow are able to sabotage the machines on purpose so that the chip reader doesn’t work. Like maybe jamming something inside it.

I just received a new VISA card to access my health savings account five weeks ago. It does not have a chip!

I wonder if those old magnetic tape degaussers that they used to sell for audio/video tape would erase the stripe without damaging the chip (if you have one).

Interesting. Good story, lots of digestable that the uninitiated can follow. NFC readers, oh so 90’s. They were common in the gas and grocery’s back then. Apple and Google pay? You are unable to use in power out situations. There has to be a powered circuit on the merchants side to use the terminals. The same with the chip and NFC , need power. The only one not needing power, is the old bump read card. Now, which could be intercepted? An, the third party on the left…. All could be intercepted. It is just, there are no known to the consumer instances of apple Google being broken into yet. That’s yet.

Mr. Krebs, please add a “Print” button to your website to make it easier to print your posts. Thanks.

Do cards issues outside the US even have mag stripes or just the chips?

Specifically EU.

Thanks

To support use in “legacy countries” most still have a magstripe, though it is strictly speaking optional by scheme rules now.

Many US gas stations continue to do non-chip transactions at the pump, continuing to make them a prime target. They also received an extension to allow them to continue using the mag-stripe past the Oct. 2017 deadline to Oct. 2020. A huge amount of fraud has been generated as a result of the extension.

Hopefully this deadline will hold and we’ll see a drop in stolen data from this area.

And winner goes to…..AmEx

If Visa had simply implemented the existing FIPS-140 standard, we could have had chipped cards sooner AND they would have worked on the web. Of course VISA would have lost their vendor lock-in so that didn’t happen. I don’t know of a single PC that can access a U.S. credit card off-the-shelf. My family’s purchases this year are 100% over the internet with no card-present validation possible. This is 100% on VISA choosing lock-in over consumer protection.

Back in 2012-2014, my team read track data from a magstripe pre-paid VISA, then used a modified Android device (pre-HCE) to successfully present the static track data to an NFC terminal. Not sure what additional controls have been implemented since then. This was concurrent with the Target hack and the thought of a mega-database being available for pulling valid cards out of the cloud for NFC presentation was a concern.

Michigan, shrieking in agony after being turned into a blob: https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/bc-us-supply-spending.png

the carding world is full off rippers we should fight against them they are the biggest criminals rippers are taking from fellow brothers without the mercy !

nowdays 90% vendors sellers are the scammers!

i hope one day the rippers get punished by the GOD.

Can’t recall the last time I swiped a card – perhaps 3-4 yrs ago?

It was about the same time that USAA dropped Mastercard.

I do remember trying to buy a business dinner in Istanbul for 10 people 5+ yrs ago away from the tourist area and being denied because my cards at the time weren’t chip-n-pin. USAA provided a chip-n-pin MC card for a few years, then dumped. Now we are stuck with chip-n-signature, but I haven’t been asked to sign anything in a few years except twice for some expensive auto repairs.

My USAA VISA card still has chip and pin, but it has been lowered in the hierarchy of negotiated verification methods so that chip and signature now comes first. Negates the whole reason I got the card.

Noting that USAA has over 83% of its cards sold to the bad actors, I recall that if you request text notification of charges against this card, you get the text only _after_ the transaction posts, and not when it happens. Since there can be a 2-3 day lag, that gives the perp a good head start. My complaints about this have gone in the bit bucket.

Sadly, there are exactly two banks that offer CHIP+PIN (with PIN priority) cards in the US. They are: First Tech Federal Credit Union (firsttechfed.com) and Target (target.com). For every other card issuer, customers financial security is not their problem.

The solution for card-not-present fraud is also not new. Virtual card numbers change with each transaction. Even if the merchant gets hacked, the next transaction is safe. Few card issuers offer virtual card number credit accounts.

My understanding is that the credit card companies don’t really want to get rid of fraud. They charge merchants a percentage of all sales to cover fraudulent charges. They actually make money by doing this. If the stop fraud, they kill a revenue source.

Great work. How can a business of this type exist for so many years without being detected and stopped by law enforcement and its owners traced?