Police in Israel are recommending that the state attorney’s office indict and prosecute two 18-year-olds suspected of operating vDOS, until recently the most popular attack service for knocking Web sites offline.

On Sept. 8, 2016, KrebsOnSecurity published a story about the hacking of vDOS, a service that attracted tens of thousands of paying customers and facilitated countless distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks over the four year period it was in business. That story named two young Israelis — Yarden Bidani and Itay Huri — as the likely owners and operators of vDOS, and within hours of its publication the two were arrested by Israeli police, placed on house arrest for 10 days, and forbidden from using the Internet for a month.

The front page of vDOS, when it was still online last year.

After those restrictions came and went, some readers expressed surprise that there were no formal charges announced against either of the young men. This week, however, Israeli police sent letters to lawyers for both men stating that the official investigation was nearing completion and that they planned to urge government prosecutors to pursue criminal charges.

The police are preparing to recommend prosecutors charge the men with computer fraud and extortion, alleging they caused more than six million shekels worth of damage (approximately USD $1.65 million).

Bidani’s attorney Perach Aroch told KrebsOnSecurity that her client has not yet been officially charged with any crime. But she said once the investigation is complete the defense will have 30 days to review the evidence and to make arguments as to why the case should be dismissed.

“They have to give us 30 days to see all the evidence and to try to convince them why they should not take this case to court,” Aroch said. “After that, [the prosecutors will] decide if it should go to trial.”

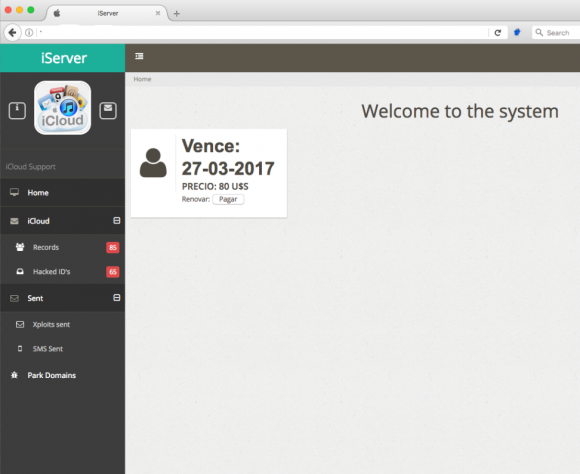

18-year-old Yarden Bidani.

The arrest of Bidani and Huri came after the police received information from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). But the United States apparently isn’t the only country weighing in on this case: According to a story published Sunday by Israeli news outlet TheMarker.com, the government of Sweden also is urging Israeli prosecutors to pursue formal charges.

It’s unclear exactly why the Swedish government is so interested in this case, but the vDOS service has been implicated in a series high-profile attacks that brought down some of the country’s largest news media Web sites last year.

Shortly after those attacks in March 2016, Somerville, Mass.-based security intelligence firm Recorded Future published an analysis linking the assaults against Swedish media sites to vDOS and to “applej4ck,” the hacker nickname allegedly used by Bidani.

In publicizing the news of vDOS’s hack last year, KrebsOnSecurity also published several months of attack logs from the vDOS service. However, those logs only dated back to May 2016.

Itay Huri’s lawyer declined to comment for this story, but TheMarker’s Amitai Ziv obtained a statement from Huri’s attorney, who accused Israeli police of applying pressure and terror through the media instead of looking for the truth.

Ziv said sources he’s spoken to believe the case will almost certainly go to trial.

“Professionals involved in the case said the likelihood of indictments in the affair is very high,” he wrote.

According to Bidani’s lawyer Aroch, the two former friends are now pointing the finger of blame at each other and are no longer speaking to one another.

“They each now accuse each other in things, so it’s a little bit of a problem,” Aroch said.

Aroch said both Bidani and Huri are free to travel and even leave the country, although both men have had their bank and PayPal accounts frozen.

Bidani and Huri allegedly started vDOS when they were 14 years old. By the time the service was shut down last September, it had attracted tens of thousands of customers who paid for attacks in PayPal (when vDOS’s PayPal accounts were shut down, the service briefly shifted to accepting payment via Bitcoin).

My Sept. 2016 investigation into the hacking of vDOS revealed that in just two of the four years the service was in operation, it brought in revenues of more than $600,000. Continue reading

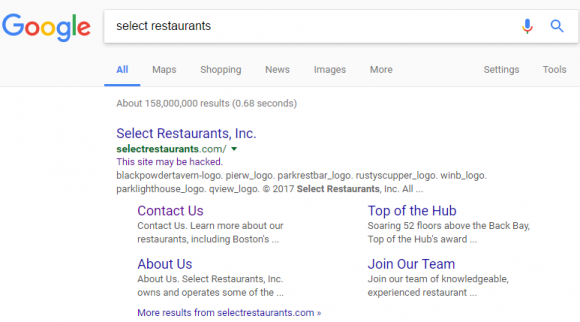

Bowling Green State University in Ohio has more than 20,000 students and faculty, and like virtually any other mid-sized state school its Internet users are constantly under attack from scammers trying to phish login credentials for email and online services.

Bowling Green State University in Ohio has more than 20,000 students and faculty, and like virtually any other mid-sized state school its Internet users are constantly under attack from scammers trying to phish login credentials for email and online services. In early 2007, PayPal (then part of the same company as eBay) began offering its hardware token for a one-time $5 fee, and at the time the company was among very few that were pushing this second-factor (something you have) in addition to passwords for user authentication. In fact, I

In early 2007, PayPal (then part of the same company as eBay) began offering its hardware token for a one-time $5 fee, and at the time the company was among very few that were pushing this second-factor (something you have) in addition to passwords for user authentication. In fact, I

On Thursday, March 16, the CEO of Defense Point Security, LLC — a Virginia company that bills itself as “the choice provider of cyber security services to the federal government” — told all employees that their W-2 tax data was handed directly to fraudsters after someone inside the company got caught in a phisher’s net.

On Thursday, March 16, the CEO of Defense Point Security, LLC — a Virginia company that bills itself as “the choice provider of cyber security services to the federal government” — told all employees that their W-2 tax data was handed directly to fraudsters after someone inside the company got caught in a phisher’s net.

Microsoft’s

Microsoft’s

On March 5, a security researcher named Bashis posted to

On March 5, a security researcher named Bashis posted to