Many U.S. citizens are bound to experience delays in getting their tax returns processed this year, thanks largely to more stringent controls enacted by Uncle Sam and the states to block fraudulent tax refund requests filed by identity thieves. A steady drip of corporate data breaches involving phished employee W-2 information is adding to the backlog, as is an apparent mass adoption by ID thieves of professional tax services for processing large numbers of phony refund requests.

According to data released this week by anti-fraud company iovation, the Internal Revenue Service is taking up to three times longer to review 2015 tax returns compared to past years.

Julie Magee, commissioner of Alabama’s Department of Revenue, said much of the delay this year at the state level is likely due to new “fraud filters” the states have put in place with Gentax, a return processing and auditing system used by about half of U.S. state revenue departments. If the states can’t outright deny a suspicious refund request, they’ll very often deny the requested electronic bank deposit and issue a paper check to the taxpayer’s known address instead.

“Many states decided they weren’t going to start paying refunds until March 1, and on our side we’ve been using all our internal fraud resources and tools to analyze the tax return before we even put it in the queue,” Magee said. “That’s delaying refunds nationwide for the IRS and the states, and it’s pretty much going to also mean a helluva lot of paper checks are going out this year.”

The added fraud filters that states are employing take advantage of data elements shared for the first time this tax season by the major online tax preparation firms such as TurboTax. The filters look for patterns known to be associated with phony refund requests, such how quickly the return was filed, or whether the same Internet address was seen completing multiple returns.

Magee said some of the states have been adding new fraud filters nearly every time they learn of another big breach involving large numbers of stolen or phished employee W2 data, a huge problem this tax season that is forcing dozens of companies large and small to disclose data breaches over the past few weeks.

“Every time we turn around getting a phone call about another breach,” Magee said. “Because of all the different breaches, the states and the IRS have been taking extreme measures to filter, filter, filter. And each time we’d get news of an additional breach, we’d start over, reprogram our fraud filters, and re-assess those returns that were not processed fully yet and those waiting to be processed.”

Magee said the Gentax software assigns each tax return a score for “wage confidence” and “identity confidence,” and that usually fraudulent tax refund requests have high wage confidence but low — if any — identity confidence. That’s because the fraudsters are filing refund requests on taxpayers for whom they already have stolen W2 information. The identity confidence in these cases is low often because the fraudsters are asking to have the money electronically deposited into an account that can’t be directly tied to the taxpayer, or they have incorrectly supplied some of the victim’s data.

“I have zero confidence that filings which match this pattern are legitimate,” Magee said. “It’s early still, but our new filtering system seems to be working. But it’s still a big unknown about the percentage of fraudulent refunds we’re not stopping.”

MORE W2 PHISHING VICTIMS

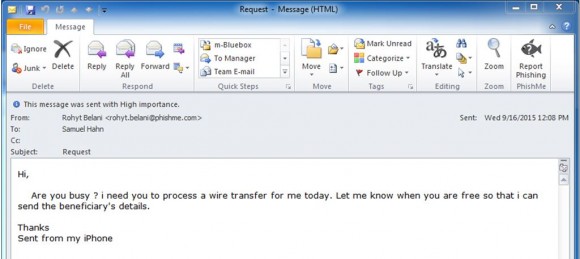

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity first warned in mid-February, thieves have been sending targeted phishing emails to human resources and finance employees at countless organizations, spoofing a message from the CEO requesting all employee W2’s in PDF format.

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity first warned in mid-February, thieves have been sending targeted phishing emails to human resources and finance employees at countless organizations, spoofing a message from the CEO requesting all employee W2’s in PDF format.

In Magee’s own state, W2 phishers hauled in tax data on an estimated 180 employees of ISCO Industries in Huntsville, and some 425 employees at the EWTN Global Catholic Network in Irondale, Ala. But those are just the ones that have been made public. Magee’s office only learned of those breaches after employees at the affected organizations reached out to journalists who then wrote about the compromises.

Over the past week, KrebsOnSecurity similarly has heard from employees at a broad range of organizations that appear to have fallen victim to W2 phishing scams, including some 28,000 employees of the market research giant Kantar Group; 17,000+ employees of Sprouts Farmer’s Market; call center software provider Aspect; computer backup software maker Acronis; Kids Dental Kare in Los Angeles; Century Fence, a fencing company in Wisconsin; Nation’s Lending Corporation, a mortgage lending firm in Independent, Ohio; QTI Group, a Wisconsin-based human resources consulting company; and the jousting-and-feasting entertainment company Medieval Times. Continue reading →

US-CERT cited an April 14 blog post by Christopher Budd at Trend Micro, which runs a program called Zero Day Initiative (ZDI) that buys security vulnerabilities and helps researchers coordinate fixing the bugs with software vendors. Budd urged Windows users to junk Quicktime, citing two new, unpatched vulnerabilities that ZDI detailed which could be used to remotely compromise Windows computers.

US-CERT cited an April 14 blog post by Christopher Budd at Trend Micro, which runs a program called Zero Day Initiative (ZDI) that buys security vulnerabilities and helps researchers coordinate fixing the bugs with software vendors. Budd urged Windows users to junk Quicktime, citing two new, unpatched vulnerabilities that ZDI detailed which could be used to remotely compromise Windows computers.

Adobe said a “critical” bug exists in all versions of Flash including Flash versions 21.0.0.197 and lower (older) across a broad range of systems, including Windows, Mac, Linux and Chrome OS. Find out if you have Flash and if so what version by visiting

Adobe said a “critical” bug exists in all versions of Flash including Flash versions 21.0.0.197 and lower (older) across a broad range of systems, including Windows, Mac, Linux and Chrome OS. Find out if you have Flash and if so what version by visiting

Earlier this week, a prominent member of a closely guarded underground cybercrime forum posted a new thread advertising the sale of a database containing the contact information on some 1.5 million customers of Verizon Enterprise.

Earlier this week, a prominent member of a closely guarded underground cybercrime forum posted a new thread advertising the sale of a database containing the contact information on some 1.5 million customers of Verizon Enterprise.

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity