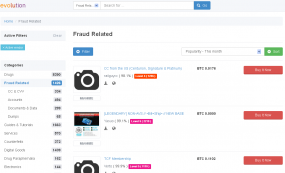

Some of the most frank and useful information about how to fight fraud comes directly from the mouths of the crooks themselves. Online cybercrime forums play a critical role here, allowing thieves to compare notes about how to evade new security roadblocks and steer clear of fraud tripwires. And few topics so reliably generate discussion on crime forums around this time of year as tax return fraud, as we’ll see in the conversations highlighted in this post.

As several stories these past few months have noted, those involved in tax refund fraud shifted more of their activities away from the Internal Revenue Service and toward state tax filings. This shift is broadly reflected in discussions on several fraud forums from 2014, in which members lament the apparent introduction of new fraud “filters” by the IRS that reportedly made perpetrating this crime at the federal level more challenging for some scammers.

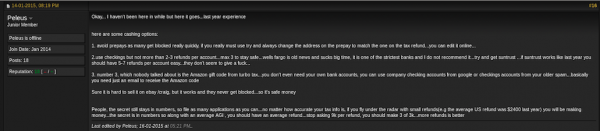

One outspoken and unrepentant tax fraudster — a ne’er-do-well using the screen name “Peleus” — reported that he had far more luck filing phony returns at the state level last year. Peleus posted the following experience to a popular fraud forum in February 2014:

“Just wanted to share a bit of my results to see if everyone is doing so bad or it just me…Federal this year has been a pain in the ass. I have about 35 applications made for federal with only 2 paid refunds…I started early in January (15-20) on TT [TurboTax] and HR [H&R Block] and made about 35 applications on Federal and State..My stats are as follows:

Federal: 35 applications (less than 10% approval rate) – average per return $2500

State: 35 apps – 15 approved (average per return $1600). State works just as great as last year, their approval rate is nearly 50% and processing time no more than 10 – 12 days.

I know that the IRS has new check filters this year but federals suck big time this year, i only got 2 refunds approved from 35 applications …all my federals are between $2300 – $2600 which is the average refund amount in the US so i wouldn’t raise any flags…I also put a small yearly salary like 25-30k….All this precautions and my results still suck big time compared to last year when i had like 30%- 35% approval rate …what the fuck changed this year? Do they check the EIN from last year’s return so you need his real employer information?”

Several seasoned members of this fraud forum responded that the IRS had indeed become more strict in validating whether the W2 information supplied by the filer had the proper Employer Identification Number (EIN), a unique tax ID number assigned to each company. The fraudsters then proceeded to discuss various ways to mine social networking sites like LinkedIn for victims’ employer information.

GET YER EINs HERE

A sidebar is probably in order here. EINs are not exactly state secrets. Public companies publish their EINs on the first page of their annual 10-K filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Still, EINs for millions of small companies here in the United States are not so easy to find, and many small business owners probably treat this information as confidential.

Nevertheless, a number of organizations specialize in selling access to EINs. One of the biggest is Dun & Bradstreet, which, as I detailed in a 2013 exposé, Data Broker Giants Hacked by ID Theft Service, was compromised for six months by a service selling Social Security numbers and other data to identity thieves like Peleus.

Last year, I heard from a source close to the investigation into the Dun & Bradstreet breach who said the thieves responsible made off with more than six million EINs. In December 2014, I asked Dun &Bradstreet about the veracity of this claim, and received a blanket statement that did not address the six million figure, but stressed that EINs are not personally identifiable information and are available to the public. Continue reading