The year 2014 may well go down in the history books as the year that extortion attacks went mainstream. Fueled largely by the emergence of the anonymous online currency Bitcoin, these shakedowns are blurring the lines between online and offline fraud, and giving novice computer users a crash course in modern-day cybercrime.

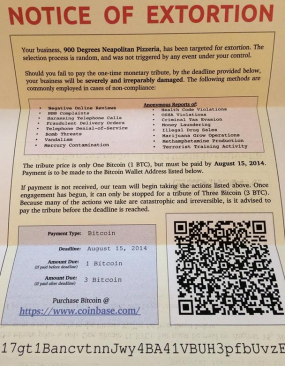

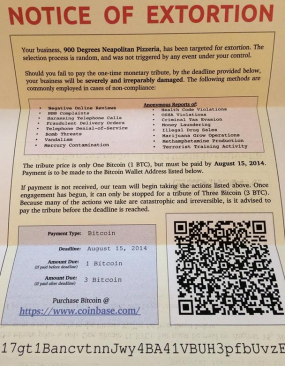

An extortion letter sent to 900 Degrees Neapolitan Pizzeria in New Hampshire.

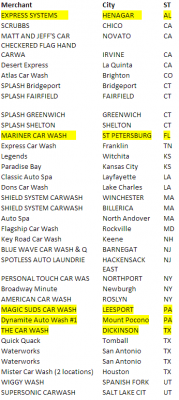

At least four businesses recently reported receiving “Notice of Extortion” letters in the U.S. mail. The letters say the recipient has been targeted for extortion, and threaten a range of negative publicity, vandalism and harassment unless the target agrees to pay a “tribute price” of one bitcoin (currently ~USD $561) by a specified date. According to the letter, that tribute price increases to 3 bitcoins (~$1,683) if the demand isn’t paid on time.

The ransom letters, which appear to be custom written for restaurant owners, threaten businesses with negative online reviews, complaints to the Better Business Bureau, harassing telephone calls, telephone denial-of-service attacks, bomb threats, fraudulent delivery orders, vandalism, and even reports of mercury contamination.

The missive encourages recipients to sign up with Coinbase – a popular bitcoin exchange – and to send the funds to a unique bitcoin wallet specified in the letter and embedded in the QR code that is also printed on the letter.

Interestingly, all three letters I could find that were posted online so far targeted pizza stores. At least two of them were mailed from Orlando, Florida.

The letters all say the amounts are due either on Aug. 1 or Aug. 15. Perhaps one reason the deadlines are so far off is that the attackers understand that not everyone has bitcoins, or even knows about the virtual currency.

“What the heck is a BitCoin?” wrote the proprietors of New Hampshire-based 900 Degrees Neapolitan Pizzeria, which posted a copy of the letter (above) on their Facebook page.

Sandra Alhilo, general manager of Pizza Pirates in Pomona, Calif., received the extortion demand on June 16.

“At first, I was laughing because I thought it had to be a joke,” Alhilo said in a phone interview. “It was funny until I went and posted it on our Facebook page, and then people put it on Reddit and the Internet got me all paranoid.”

Nicholas Weaver, a researcher at the International Computer Science Institute (ICSI) and at the University California, Berkeley, said these extortion attempts cost virtually nothing and promise a handsome payoff for the perpetrators.

“From the fraudster’s perspective, the cost of these attacks is a stamp and an envelope,” Weaver said. “This type of attack could be fairly effective. Some businesses — particularly restaurant establishments — are very concerned about negative publicity and reviews. Bad Yelp reviews, tip-offs to the health inspector..that stuff works and isn’t hard to do.”

While some restaurants may be an easy mark for this sort of crime, Weaver said the extortionists in this case are tangling with a tough adversary — The U.S. Postal Service — which takes extortion crimes perpetrated through the U.S. mail very seriously.

“There is a lot of operational security that these guys might have failed at, because this is interstate commerce, mail fraud, and postal inspector territory, where the gloves come off,” Weaver said. “I’m willing to bet there are several tools available to law enforcement here that these extortionists didn’t consider.”

It’s not entirely clear if or why extortionists seem to be picking on pizza establishments, but it’s probably worth noting that the grand-daddy of all pizza joints — Domino’s Pizza in France — recently found itself the target of a pricey extortion attack earlier this month after hackers threatened to release the stolen details on more than 650,000 customers if the company failed to pay a ransom of approximately $40,000).

Meanwhile, Pizza Pirates’s Alhilo says the company has been working with the local U.S. Postal Inspector’s office, which was very interested in the letter. Alhilo said her establishment won’t be paying the extortionists.

“We have no intention of paying it,” she said. “Honestly, if it hadn’t been a slow day that Monday I might have just throw the letter out because it looked like junk mail. It’s annoying that someone would try to make a few bucks like this on the backs of small businesses.” Continue reading →

![Bulba[dot]cc, as it looked in May 2011.](https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/bulba-dot-cc-e-600x389.png)