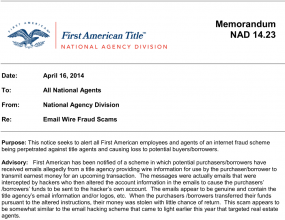

Earlier this month, I wrote about an organized cybercrime gang that has been hacking into HR departments at organizations across the country and filing fraudulent tax refund requests with the IRS on employees of those victim firms. Today, we’ll look a bit closer at the activities of this crime gang, which appears to have targeted a large number of healthcare and senior living organizations that were all using the same third-party payroll and HR services provider.

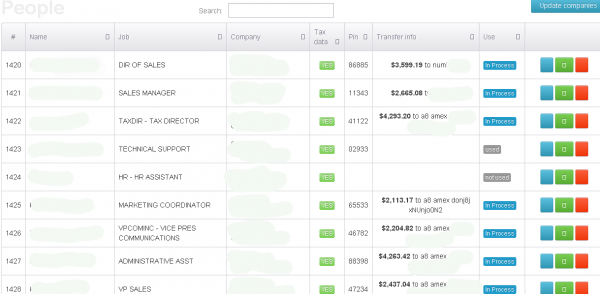

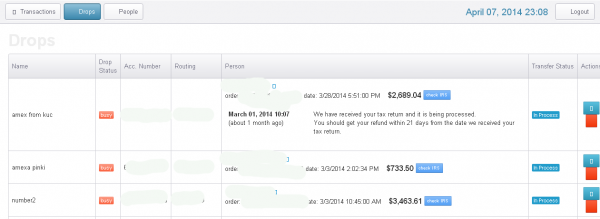

As I wrote in the previous story, KrebsOnSecurity encountered a Web-based control panel that an organized criminal gang has been using to track bogus tax returns filed on behalf of employees at hacked companies whose HR departments had been relieved of W-2 forms for all employees.

As I wrote in the previous story, KrebsOnSecurity encountered a Web-based control panel that an organized criminal gang has been using to track bogus tax returns filed on behalf of employees at hacked companies whose HR departments had been relieved of W-2 forms for all employees.

Among the organizations listed in that panel were Plaintree Inc. and Griffin Faculty Practice Plan. Both entities are subsidiaries of Derby, Conn.-based Griffin Health Services Corp.

Steve Mordecai, director of human resources at Griffin Hospital, confirmed that a security breach at his organization had exposed the personal and tax data on “a limited number of employees for Griffin Health Services Corp. and Griffin Hospital.” Mordecai said the attackers obtained the information after stealing the organization’s credentials at a third-party payroll and HR management provider called UltiPro.

Mordecai said that the bad guys only managed to steal data on roughly four percent of the organization’s employees, but he declined to say how many employees the healthcare system currently has. An annual report (PDF) from 2009 states that Griffin Hospital alone had more than 1,384 employees.

“Fortunately for us it was a limited number of employees who may have had their information breached or stolen,” Mordecai said. “There is a criminal investigation with the FBI that is ongoing, so I can’t say much more.”

The FBI did not return calls seeking comment. But according Reuters, the FBI recently circulated a private notice to healthcare providers, warning that the “cybersecurity systems at many healthcare providers are lax compared to other sectors, making them vulnerable to attacks by hackers searching for Americans’ personal medical records and health insurance data.”

According to information in their Web-based control panel, the attackers responsible for hacking into Griffin also may have infiltrated an organization called Medical Career Center Inc., but that could not be independently confirmed.

This crime gang also appears to have targeted senior living facilities, including SL Bella Terra LLC, a subsidiary of Chicago-based Senior Lifestyle Corp, an assisted living firm that operates in seven states. Senior Living did not return calls seeking comment.

In addition, the attackers hit Swan Home Health LLC in Menomonee Falls, Wisc., a company that recently changed its named to Enlivant. Monica Lang, vice president of communications for Enlivant, said Swan Home Health is a subsidiary of Chicago-based Assisted Living Concepts Inc., an organization that owns and operates roughly 200 assisted living facilities in 20 states.

ALC disclosed in March 2014 that a data breach in December 2013 had exposed the personal information on approximately 43,600 current and former employees. In its March disclosure, ALC said that its internal employee records were compromised after attackers stole login credentials to the company’s third-party payroll provider.

That disclosure didn’t name the third-party provider, but every victim organization I’ve spoken with that’s been targeted by this crime gang had outsourced their payroll and/or human resources operations to UltiPro.

Enlivant’s Lang confirmed that the company also relied on UltiPro, and that some employees have come forward to report attempts to file fraudulent tax refunds on their behalf with the IRS.

“We believe that [the attackers] accessed employee names, addresses, birthdays, Social Security numbers and pay information, which is plenty to get someone going from a tax fraud perspective,” Lang said in a telephone interview. Continue reading