Hacked Web sites aren’t just used for hosting malware anymore. Increasingly, they are being retrofitted with tools that let miscreants harness the compromised site’s raw server power for attacks aimed at knocking other sites offline.

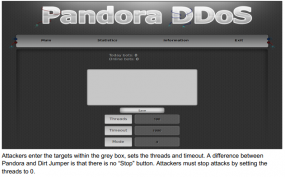

It has long been standard practice for Web site hackers to leave behind a Web-based “shell,” a tiny “backdoor” program that lets them add, delete and run files on compromised server. But in a growing number of Web site break-ins, the trespassers also are leaving behind simple tools called “booter shells,” which allow the miscreants to launch future denial-of-service attacks without the need for vast networks of infected zombie computers.

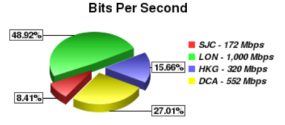

According to Prolexic, an anti-DDoS company I’ve been working with for the past few weeks to ward off attacks on my site, with booter shells DDoS attacks can be launched more readily and can cause more damage, with far fewer machines. “Web servers typically have 1,000+ times the capacity of a workstation, providing hackers with a much higher yield of malicious traffic with the addition of each infected web server,” the company said in a recent advisory.

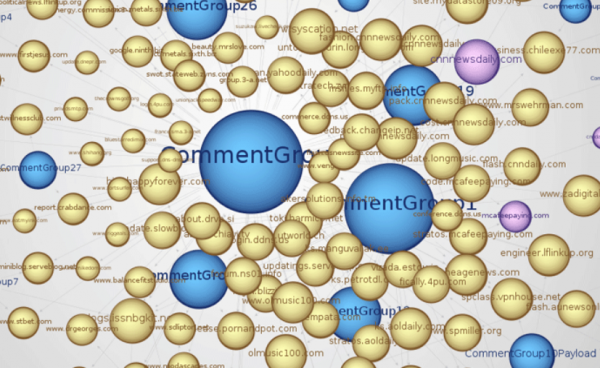

The proliferation of booter shells has inevitably led to online services that let paying customers leverage these booter shell-backdoored sites. One such service is absoboot.com, also reachable at twbooter.com. Anyone can sign up, fund the account with Paypal or one of several other virtual currencies, and start attacking. The minimum purchase via PayPal is $15, which buys you about 5 hours worth of keeping a site down or at least under attack.

If you’d prefer to knock an individual internet user offline as opposed to a Web site, absoBoot includes a handy free tool that lets users discover someone’s IP address. Just select an image of your choice (or use the pre-selected image) and send the target a customized link that is specific to your absoBoot account. The link to the picture is mapped to a domain crafted to look like it takes you to imageshack.us; closer inspection of the link shows that it fact ends in “img501.ws,” and records the recipients IP address if he or she views the image. Continue reading