The creator of a popular crimeware package known as the Phoenix Exploit Kit was arrested in his native Russia for distributing malicious software and for illegally possessing multiple firearms, according to underground forum posts from the malware author himself.

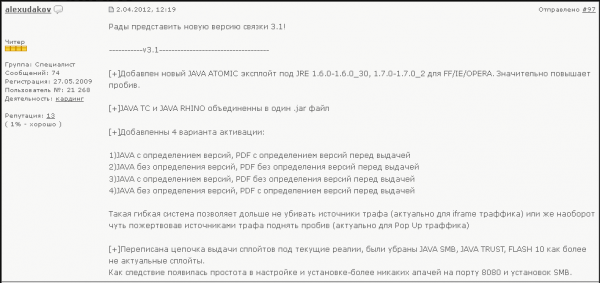

The last version of the Phoenix Exploit Kit. Source: Xylibox.com

The Phoenix Exploit Kit is a commercial crimeware tool that until fairly recently was sold by its maker in the underground for a base price of $2,200. It is designed to booby-trap hacked and malicious Web sites so that they foist drive-by downloads on visitors.

Like other exploit packs, Phoenix probes the visitor’s browser for the presence of outdated and insecure versions of browser plugins like Java, and Adobe Flash and Reader. If the visitor is unlucky enough to have fallen behind in applying updates, the exploit kit will silently install malware of the attacker’s choosing on the victim’s PC (Phoenix targets only Microsoft Windows computers).

The author of Phoenix — a hacker who uses the nickname AlexUdakov on several forums — does not appear to have been overly concerned about covering his tracks or hiding his identity. And as we’ll see in a moment, his online persona has been all-too-willing to discuss his current legal situation with former clients and fellow underground denizens.

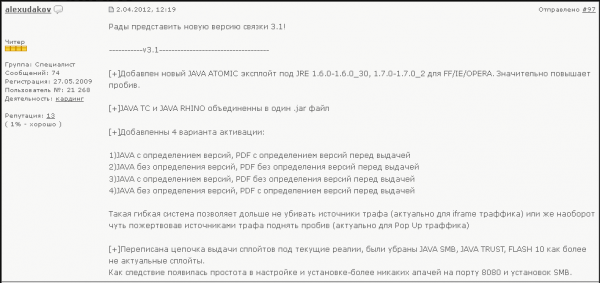

Exploit.in forum member AlexUdakov selling his Phoenix Exploit Kit.

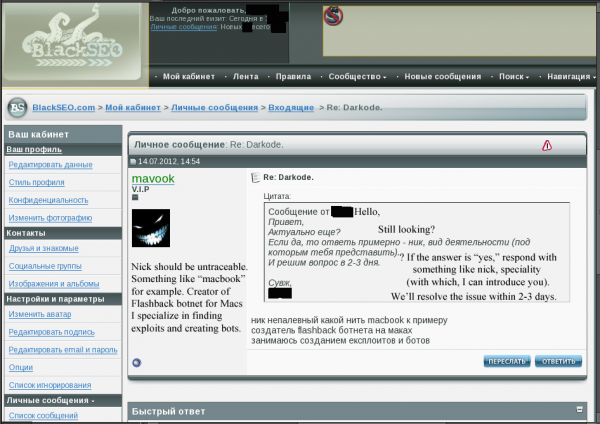

For example, AlexUdakov was a member of Darkode.com, a fairly exclusive English-language cybercrime forum that I profiled last week. That post revealed that the administrator accounts for Darkode had been compromised in a recent break-in, and that the intruders were able to gain access to private communications of the administrators. That access included authority to view full profiles of Darkode members, as well as the private email addresses of Darkode members.

AlexUdakov registered at Darkode using the address “nrew89@gmail.com”. That email is tied to a profile at Vkontakte.ru (a Russian version of Facebook) for one Andrey Alexandrov, a 23-year-old male (born May 20, 1989) from Yoshkar-Ola, a historic city of about a quarter-million residents situated on the banks of the Malaya Kokshaga river in Russia, about 450 miles east of Moscow.

AKS-74u rifles. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

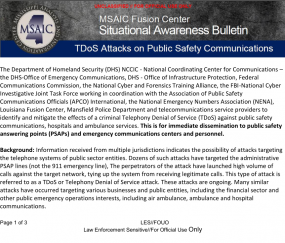

That nrew89@gmail.com address also is connected to accounts at several Russian-language forums and Web sites dedicated to discussing guns, including talk.guns.ru and popgun.ru. This is interesting because, as I was searching AlexUdakov’s Phoenix Exploit kit sales postings on various cybercrime forums, I came across him discussing guns on one of his sales threads at exploit.in, a semi-exclusive underground forum. There, a user with the nickname AlexUdakov had been selling Phoenix Exploit Kit for many months, until around July 2012, when customers on exploit.in began complaining that he was no longer responding to sales and support requests. Meanwhile, AlexUdakov account remained silent for many months.

Then, in February 2013, AlexUdakov began posting again, explaining his absence by detailing his arrest by the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Russian equivalent of the FBI. The Phoenix Exploit Kit author explained that he was arrested by FSB officers for distributing malware and the illegal possession of firearms, including two AKS-74U assault rifles, a Glock, a TT (Russian-made pistol), and a PM (also known as a Makarov).

Continue reading →

The MS13-036 update, first released on Tuesday, fixes four vulnerabilities in the Windows kernel-mode driver. In an advisory released April 9, the company said it had removed the download links to the patch while it investigates the source of the problem:

The MS13-036 update, first released on Tuesday, fixes four vulnerabilities in the Windows kernel-mode driver. In an advisory released April 9, the company said it had removed the download links to the patch while it investigates the source of the problem: