Peter is an IT manager for a technology manufacturer that got hit with a Russian ransomware strain called “Zeppelin” in May 2020. He’d been on the job less than six months, and because of the way his predecessor architected things, the company’s data backups also were encrypted by Zeppelin. After two weeks of stalling their extortionists, Peter’s bosses were ready to capitulate and pay the ransom demand. Then came the unlikely call from an FBI agent. “Don’t pay,” the agent said. “We’ve found someone who can crack the encryption.”

Peter, who spoke candidly about the attack on condition of anonymity, said the FBI told him to contact a cybersecurity consulting firm in New Jersey called Unit 221B, and specifically its founder — Lance James. Zeppelin sprang onto the crimeware scene in December 2019, but it wasn’t long before James discovered multiple vulnerabilities in the malware’s encryption routines that allowed him to brute-force the decryption keys in a matter of hours, using nearly 100 cloud computer servers.

In an interview with KrebsOnSecurity, James said Unit 221B was wary of advertising its ability to crack Zeppelin ransomware keys because it didn’t want to tip its hand to Zeppelin’s creators, who were likely to modify their file encryption approach if they detected it was somehow being bypassed.

This is not an idle concern. There are multiple examples of ransomware groups doing just that after security researchers crowed about finding vulnerabilities in their ransomware code.

“The minute you announce you’ve got a decryptor for some ransomware, they change up the code,” James said.

But he said the Zeppelin group appears to have stopped spreading their ransomware code gradually over the past year, possibly because Unit 221B’s referrals from the FBI let them quietly help nearly two dozen victim organizations recover without paying their extortionists.

In a blog post published today to coincide with a Black Hat talk on their discoveries, James and co-author Joel Lathrop said they were motivated to crack Zeppelin after the ransomware gang started attacking nonprofit and charity organizations.

“What motivated us the most during the leadup to our action was the targeting of homeless shelters, nonprofits and charity organizations,” the two wrote. “These senseless acts of targeting those who are unable to respond are the motivation for this research, analysis, tools, and blog post. A general Unit 221B rule of thumb around our offices is: Don’t [REDACTED] with the homeless or sick! It will simply trigger our ADHD and we will get into that hyper-focus mode that is good if you’re a good guy, but not so great if you are an ***hole.”

The researchers said their break came when they understood that while Zeppelin used three different types of encryption keys to encrypt files, they could undo the whole scheme by factoring or computing just one of them: An ephemeral RSA-512 public key that is randomly generated on each machine it infects.

“If we can recover the RSA-512 Public Key from the registry, we can crack it and get the 256-bit AES Key that encrypts the files!” they wrote. “The challenge was that they delete the [public key] once the files are fully encrypted. Memory analysis gave us about a 5-minute window after files were encrypted to retrieve this public key.”

Unit 221B ultimately built a “Live CD” version of Linux that victims could run on infected systems to extract that RSA-512 key. From there, they would load the keys into a cluster of 800 CPUs donated by hosting giant Digital Ocean that would then start cracking them. The company also used that same donated infrastructure to help victims decrypt their data using the recovered keys.

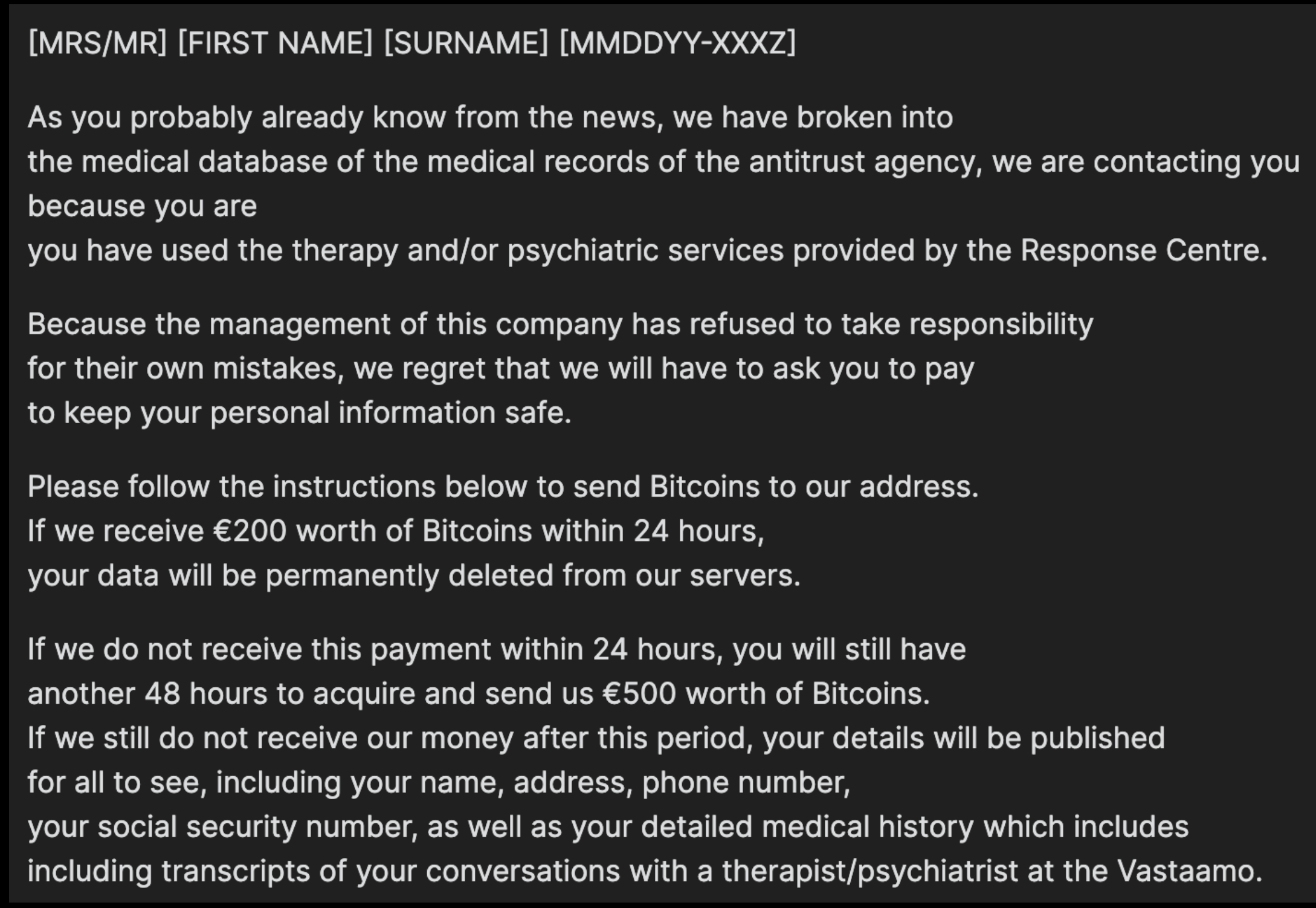

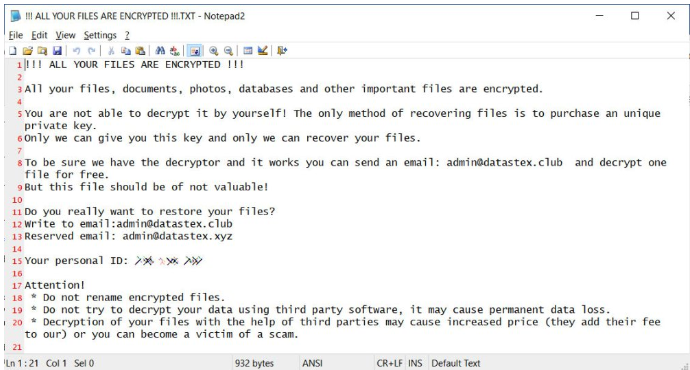

A typical Zeppelin ransomware note.

Jon is another grateful Zeppelin ransomware victim who was aided by Unit 221B’s decryption efforts. Like Peter, Jon asked that his last name and that of his employer be omitted from the story, but he’s in charge of IT for a mid-sized managed service provider that got hit with Zeppelin in July 2020.

The attackers that savaged Jon’s company managed to phish credentials and a multi-factor authentication token for some tools the company used to support customers, and in short order they’d seized control over the servers and backups for a healthcare provider customer.

Jon said his company was reluctant to pay a ransom in part because it wasn’t clear from the hackers’ demands whether the ransom amount they demanded would provide a key to unlock all systems, and that it would do so safely.

“They want you to unlock your data with their software, but you can’t trust that,” Jon said. “You want to use your own software or someone else who’s trusted to do it.”

In August 2022, the FBI and the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) issued a joint warning on Zeppelin, saying the FBI had “observed instances where Zeppelin actors executed their malware multiple times within a victim’s network, resulting in the creation of different IDs or file extensions, for each instance of an attack; this results in the victim needing several unique decryption keys.” Continue reading