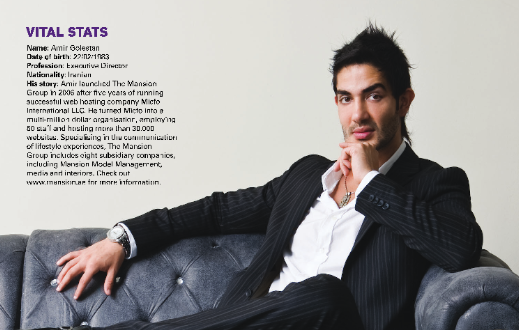

A visualization of the Internet made using network routing data. Image: Barrett Lyon, opte.org.

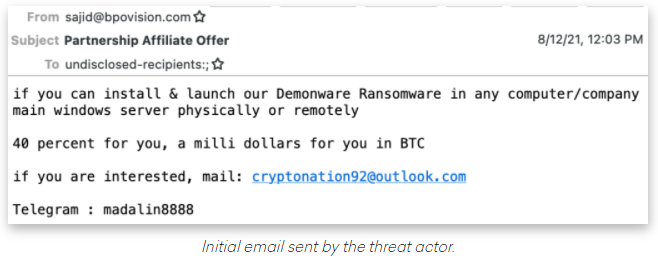

Imagine being able to disconnect or redirect Internet traffic destined for some of the world’s biggest companies — just by spoofing an email. This is the nature of a threat vector recently removed by a Fortune 500 firm that operates one of the largest Internet backbones.

Based in Monroe, La., Lumen Technologies Inc. [NYSE: LUMN] (formerly CenturyLink) is one of more than two dozen entities that operate what’s known as an Internet Routing Registry (IRR). These IRRs maintain routing databases used by network operators to register their assigned network resources — i.e., the Internet addresses that have been allocated to their organization.

The data maintained by the IRRs help keep track of which organizations have the right to access what Internet address space in the global routing system. Collectively, the information voluntarily submitted to the IRRs forms a distributed database of Internet routing instructions that helps connect a vast array of individual networks.

There are about 70,000 distinct networks on the Internet today, ranging from huge broadband providers like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon to many thousands of enterprises that connect to the edge of the Internet for access. Each of these so-called “Autonomous Systems” (ASes) make their own decisions about how and with whom they will connect to the larger Internet.

Regardless of how they get online, each AS uses the same language to specify which Internet IP address ranges they control: It’s called the Border Gateway Protocol, or BGP. Using BGP, an AS tells its directly connected neighbor AS(es) the addresses that it can reach. That neighbor in turn passes the information on to its neighbors, and so on, until the information has propagated everywhere [1].

A key function of the BGP data maintained by IRRs is preventing rogue network operators from claiming another network’s addresses and hijacking their traffic. In essence, an organization can use IRRs to declare to the rest of the Internet, “These specific Internet address ranges are ours, should only originate from our network, and you should ignore any other networks trying to lay claim to these address ranges.”

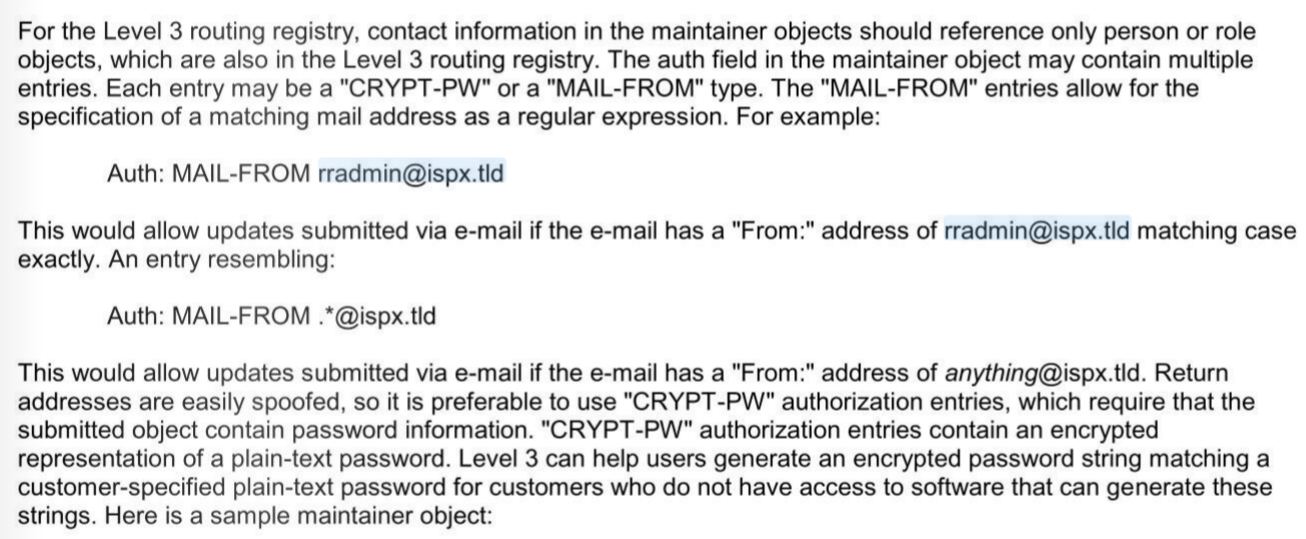

In the early days of the Internet, when organizations wanted to update their records with an IRR, the changes usually involved some amount of human interaction — often someone manually editing the new coordinates into an Internet backbone router. But over the years the various IRRs made it easier to automate this process via email.

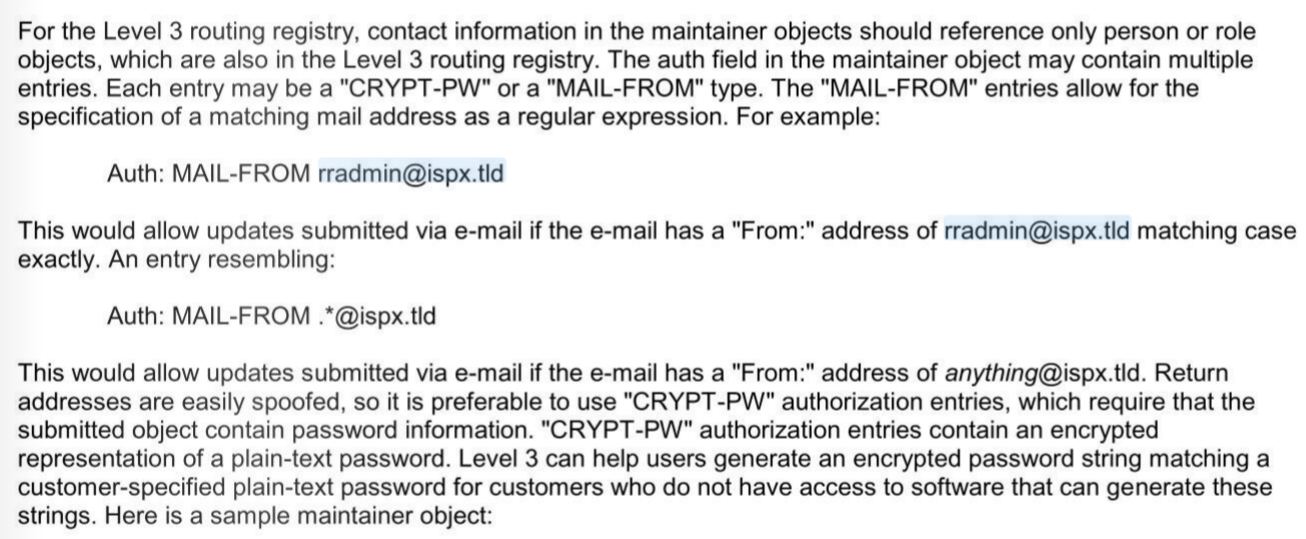

For a long time, any changes to an organization’s routing information with an IRR could be processed via email as long as one of the following authentication methods was successfully used:

-CRYPT-PW: A password is added to the text of an email to the IRR containing the record they wish to add, change or delete (the IRR then compares that password to a hash of the password);

-PGPKEY: The requestor signs the email containing the update with an encryption key the IRR recognizes;

-MAIL-FROM: The requestor sends the record changes in an email to the IRR, and the authentication is based solely on the “From:” header of the email.

Of these, MAIL-FROM has long been considered insecure, for the simple reason that it’s not difficult to spoof the return address of an email. And virtually all IRRs have disallowed its use since at least 2012, said Adam Korab, a network engineer and security researcher based in Houston.

All except Level 3 Communications, a major Internet backbone provider acquired by Lumen/CenturyLink.

“LEVEL 3 is the last IRR operator which allows the use of this method, although they have discouraged its use since at least 2012,” Korab told KrebsOnSecurity. “Other IRR operators have fully deprecated MAIL-FROM.”

Importantly, the name and email address of each Autonomous System’s official contact for making updates with the IRRs is public information.

Korab filed a vulnerability report with Lumen demonstrating how a simple spoofed email could be used to disrupt Internet service for banks, telecommunications firms and even government entities.

“If such an attack were successful, it would result in customer IP address blocks being filtered and dropped, making them unreachable from some or all of the global Internet,” Korab said, noting that he found more than 2,000 Lumen customers were potentially affected. “This would effectively cut off Internet access for the impacted IP address blocks.”

The recent outage that took Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp offline for the better part of a day was caused by an erroneous BGP update submitted by Facebook. That update took away the map telling the world’s computers how to find its various online properties.

Now consider the mayhem that would ensue if someone spoofed IRR updates to remove or alter routing entries for multiple e-commerce providers, banks and telecommunications companies at the same time.

“Depending on the scope of an attack, this could impact individual customers, geographic market areas, or potentially the [Lumen] backbone,” Korab continued. “This attack is trivial to exploit, and has a difficult recovery. Our conjecture is that any impacted Lumen or customer IP address blocks would be offline for 24-48 hours. In the worst-case scenario, this could extend much longer.”

Lumen told KrebsOnSecurity that it continued offering MAIL-FROM: authentication because many of its customers still relied on it due to legacy systems. Nevertheless, after receiving Korab’s report the company decided the wisest course of action was to disable MAIL-FROM: authentication altogether.

“We recently received notice of a known insecure configuration with our Route Registry,” reads a statement Lumen shared with KrebsOnSecurity. “We already had mitigating controls in place and to date we have not identified any additional issues. As part of our normal cybersecurity protocol, we carefully considered this notice and took steps to further mitigate any potential risks the vulnerability may have created for our customers or systems.”

Level3, now part of Lumen, has long urged customers to avoid using “Mail From” for authentication, but until very recently they still allowed it.

Continue reading →

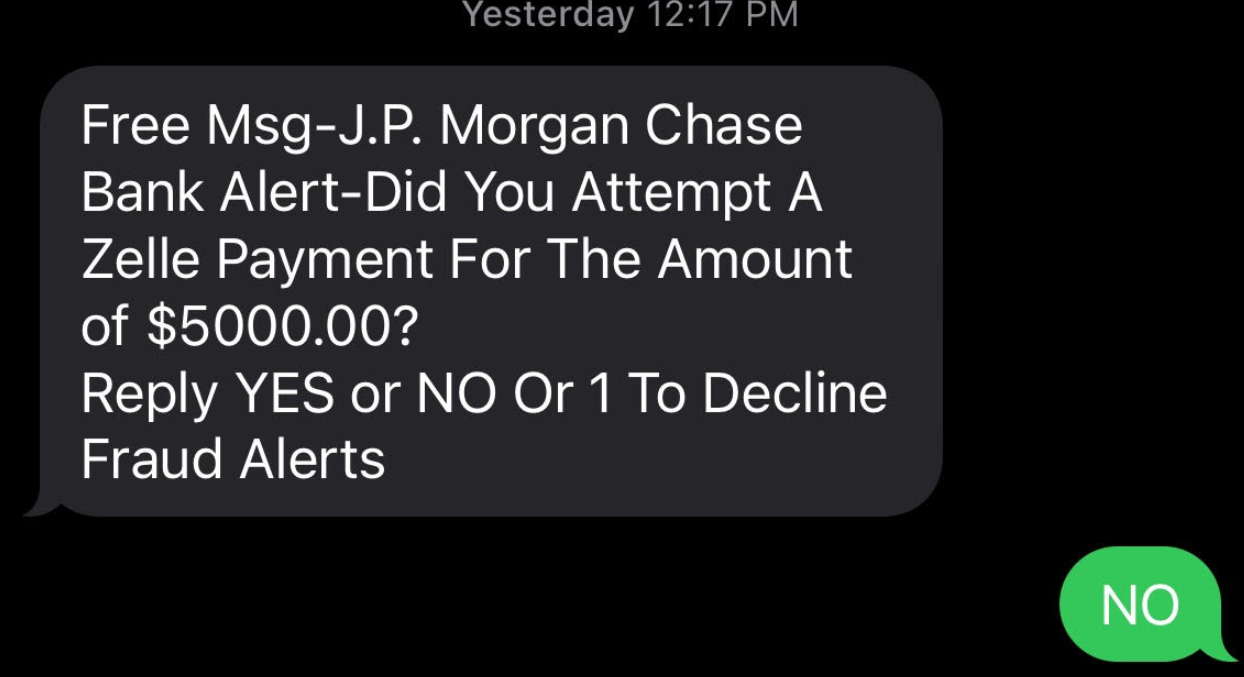

The fraudster then uses the code to complete the password reset process, and then changes the victim’s online banking password. The fraudster then uses Zelle to transfer the victim’s funds to others.

The fraudster then uses the code to complete the password reset process, and then changes the victim’s online banking password. The fraudster then uses Zelle to transfer the victim’s funds to others.