A Pennsylvania man who operated one of the Internet’s longest-running online attack-for-hire or “booter” services was sentenced to five years probation today. While the young man’s punishment was heavily tempered by his current poor health, the defendant’s dietary choices may have contributed to both his capture and the lenient sentencing: Investigators say the onetime booter boss’s identity became clear after he ordered a bacon and chicken pizza delivered to his home using the same email address he originally used to register his criminal attack service.

David Bukoski, 24, of Hanover Township, Pa., pleaded guilty to running Quantum Stresser, an attack-for-hire business — also known as a “booter” or “stresser” service — that helped paying customers launch tens of thousands of digital sieges capable of knocking Web sites and entire network providers offline.

The landing page for the Quantum Stresser attack-for-hire service.

Investigators say Bukoski’s booter service was among the longest running services targeted by the FBI, operating since at least 2012. The government says Quantum Stresser had more than 80,000 customer subscriptions, and that during 2018 the service was used to conduct approximately 50,000 actual or attempted attacks targeting people and networks worldwide.

The Quantum Stresser Web site — quantumstress[.]net — was among 15 booter services that were seized by U.S. and international authorities in December 2018 as part of a coordinated takedown targeting attack-for-hire services.

Federal prosecutors in Alaska said search warrants served on the email accounts Bukoski used in conjunction with Quantum Stresser revealed that he was banned from several companies he used to advertise and accept payments for the booter service.

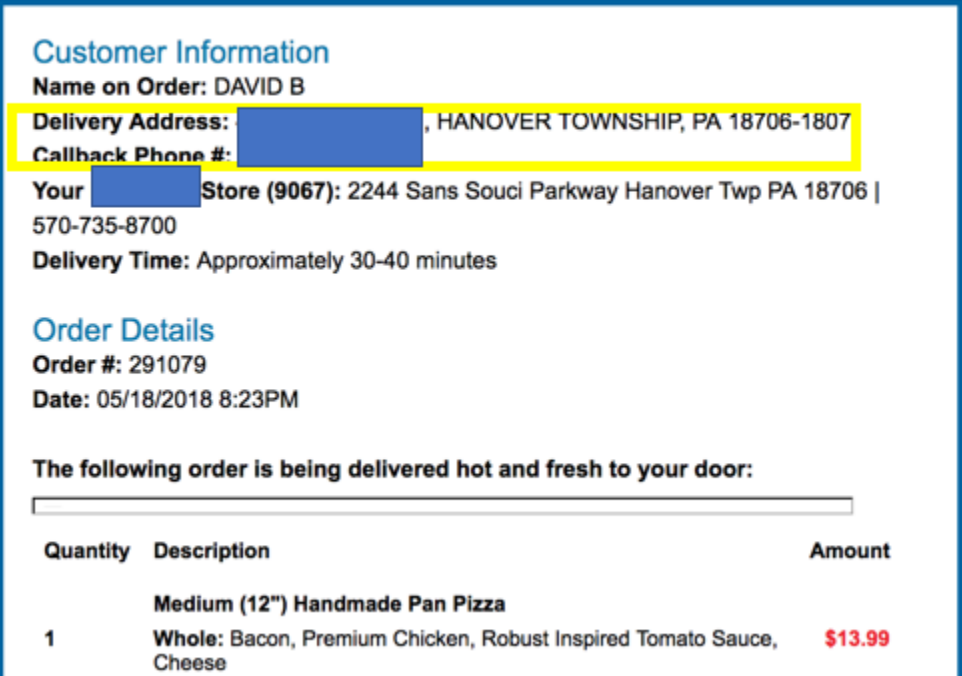

The government’s sentencing memorandum says Bukoski’s replies demanding to know the reasons for the suspensions were instrumental in discovering his real name. FBI agents were able to zero in on Bukoski’s real-life location after a review of his email account showed a receipt from May 2018 in which he’d gone online and ordered a handmade pan pizza to be delivered to his home address.

When an online pizza delivery order brings FBI agents to raid your home.

While getting busted on account of ordering a pizza online might sound like a bone-headed or rookie mistake for a cybercriminal, it is hardly unprecedented. In 2012 KrebsOnSecurity wrote about the plight of Yuriy “Jtk” Konovalenko, a then 30-year-old Ukrainian man who was rounded up as part of an international crackdown on an organized crime gang that used the ZeuS malware to steal tens of millions of dollars from companies and consumers. In that case, Konovalenko ultimately unmasked himself because he used his Internet connection to order the delivery of a “Veggie Roma” pizza to his apartment in the United Kingdom. Continue reading

As

As