A new rash of credit and debit card scams involving bogus sub-$15 charges and attributed to a company called “BLS Weblearn” is part of a prolific international scheme designed to fleece unwary consumers. This post delves deeper into the history and identity of the credit card processing network that has been enabling this type of activity for years.

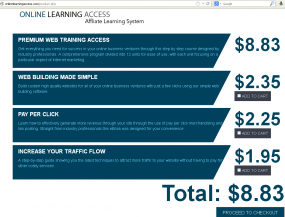

onlinelearningaccess.com, one of the fraudulent affiliate marketing schemes that powers these bogus micropayments.

At issue are a rash of phony charges levied against countless consumers for odd amounts — such as $10.37, or $12.96. When they appear on your statement, the charges generally reference a company in St. Julians, Malta such as BLS*Weblearn or PLI*Weblearn, and include a 1-888 number that may or may not work (the most common being 888-461-2032 and 888-210-6574).

I began hearing from readers about this early this month, in part because of my previous sleuthing on an eerily similar scheme that also leveraged payment systems in Malta to put through unauthorized junk charges ($9.84) for “online learning” software systems. Unfortunately, while the names of the companies and payment systems have changed, this latest scam appears to be remarkably similar in every way.

Reading up on this latest scam, it appears that the payments are being processed by a company called BlueSnap, which variously lists its offices in Massachusetts, California, Israel, Malta and London. Oddly enough, the payment network used by the $9.84 scams that surfaced last year — Credorax — also lists offices in Massachusetts, Israel, London and Malta.

And, just like with the $9.84 scam, this latest micropayment fraud scheme involves an extremely flimsy-looking affiliate income model that seems merely designed for abuse. According to information from several banks contacted for this story, early versions of this scam (in which fraudulent transactions were listed on statements as PLI*WEBLEARN) leveraged pliblue.com, formerly associated with a company called Plimus, a processor that also lists offices in California and Israel (in addition to Ukraine).

The very first time I encountered Plimus was in Sept. 2011, when I profiled an individual responsible for selling access to tens of thousands of desktop computers that were hacked and seeded with the TDSS botnet. That miscreant — a fellow who used the nickname “Fizot” — had been using Plimus to accept credit card payments for awmproxy.net, an anonymization service that was sold primarily to individuals engaged in computer fraud.

Apparently, the Internet has been unkind to Plimus’s online reputation, because not long ago the company changed its name to BlueSnap. This blog has a few ideas about what motivated the name change, noting that it might have been prompted in part by a class action lawsuit (PDF) against Plimus which alleges that the company’s marketing campaigns include the “mass production of fabricated consumer reviews, testimonials and fake blogs that are all intended to deceive consumers seeking a legitimate product and induce them to pay. Yet, after consumers pay for access to any of these digital goods websites, they quickly realize that the promotional materials and representations were blatantly false.”

Damon McCoy, an associate professor of computer science at George Mason University, allowed that the bogus charges coming from BlueSnap’s payment network could be little more than abuse generated by a handful of bad guys who just happen to be using the company’s network. Then again, McCoy said, Plimus has long been associated with these schemes.

“Plimus has been doing processing for criminals for a while,” McCoy said. “Most of it seems to have been on the criminal-to-criminal side of payments.”

BlueSnap did not immediately respond to requests for comment. I will update this story in the event that they do.

As with the $9.84 scheme, this latest round of phony charges appears tied to an affiliate marketing scheme for “online learning” (hence, the “Weblearn” notation on victims’ credit card statements). One site that’s connected to the Weblearn scheme is onlinelearningaccess.com, which actually includes commented-out code hidden in its HTML content stating that “the charge will appear on your credit card as WebLearn8884612032.”

That same site is closely tied to a network of other flimsy affiliate learning systems, including greatweblearning.com, jnselearning.com, and learnonlinemembers.com. As we can see from the checkout page at onlinelearningaccess.com, the base price of the “system” is $8.83, but different checkout totals can be achieved ($11.08 and $10.78, e.g.) simply by selecting different items to add to your shopping cart.

Unfortunately, these types of schemes are as old as the Internet, and will be with us as long as there are companies willing to engage in so-called “high-risk” credit card processing — handling transactions for things like online gaming, rogue Internet pharmacies, fake antivirus software, and counterfeit/knockoff handbags and jewelry.

There is an entire series on the sidebar of this blog called “Pharma Wars,” which chronicles the exploits of perhaps the most infamous high-risk processor of all time — a Russian company called ChronoPay and its now-imprisoned CEO. While ChronoPay was most known for processing payments for spam-advertised pill shops and fake antivirus affiliate programs, it also was caught up in a micropayment scheme that for years put through bogus, sub-$10 transactions on consumers credit cards (usually for some kind of software or ebooks program).

If you see charges like these or any other activity on your credit or debit card that you did not authorize, contact your bank and report the fraud immediately. I think it’s also a good idea in cases like this to request a new card in the odd chance your bank doesn’t offer it: After all, it’s a good bet that your card is in the hands of crooks, and is likely to be abused like this again.

For more on this scam, check out these posts from DailyKos and Consumerist.

Update: I heard back from BlueSnap CEO Ralph Dangelmaier, who said BlueSnap terminated the merchant 10 days before my story ran. Dangelmaier said he believes the merchant in question was a legitimate affiliate program that got hacked. BlueSnap vetted the merchant before allowing it onto its payment network, and even purchased the affiliate learning program. He acknowledged, however, that it was indeed unusual that the affiliate program doesn’t appear to have been marketed on the Internet to attract real-life affiliates.

“We think one happened is one of their affiliates got hacked into and might have done something wrong,” Dangelmaier said. “As soon as we saw suspicious transactions, we refunded any customer payments we thought were tied to those. We went out and bought the product ahead of time as part of our due diligence and we actually used it. It was an online training tool. We’re working very closely with the acquiring banks, Visa and the authorities to try to help.”