In June 2011, Russian authorities arrested Pavel Vrublevsky, co-founder of ChronoPay, Russia’s largest processor of online payments, for allegedly hiring a hacker to attack his company’s rivals. New evidence suggests that Vrublevsky’s arrest was the product of a bribe paid by Igor Gusev, the other co-founder of ChronoPay and a man wanted by Russian police as a spam kingpin.

Igor Gusev, in an undated photo taken at a family birthday celebration.

Two years after forming ChronoPay in 2003, Gusev and Vrublevsky parted ways. Not long after that breakup, Gusev would launch Glavmed and its sister program SpamIt, affiliate operations that paid the world’s most notorious spammers millions of dollars to promote rogue Internet pharmacies. Not to be outdone, Vrublevsky started his own rogue pharmacy program, Rx-Promotion, in 2007, contracting with some of the same spammers who were working at Gusev’s businesses.

By 2009, the former partners were actively trying to scuttle each others’ businesses. Vrublevsky allegedly paid hackers to break into and leak the contact and earnings data from GlavMed/SpamIt. He also reportedly paid a man named Igor “Engel” Artimovich to launch a volley of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against SpamIt.

Gusev told me he long suspected Artimovich was involved in the attacks, and that he had information that Vrublevsky hired Artimovich to attack ChronoPay’s rivals while they were locked in a competition for a lucrative contract to process online payments for Aeroflot, Russia’s biggest airline.

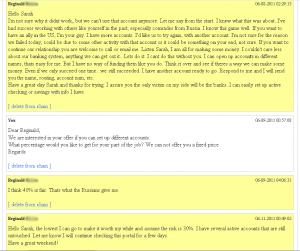

Last month, hundreds of chat conversations apparently between Gusev and his right-hand man, Dmitry Stupin, were leaked online. They indicate that Gusev may have caused Vrublevsky’s arrest by paying Russian law enforcement investigators to go after Artimovich.

Over the past year, Gusev has insisted in numerous phone interviews that the increasingly public conflict between him and Vrublevsky was not a “war,” but more of a personal spat. But if the chat below is accurate, Gusev most certainly viewed the conflict as a war all along.

The following is from a leaked chat, allegedly between Gusev and Stupin, dated Sept. 26, 2010. The two men had already decided to close SpamIt, and were considering whether to do the same with GlavMed. “Red,” mentioned twice in the discussion below, is a reference to Vrublevsky, also known as “RedEye.”

Gusev: $2k from HzMedia to China – it’s mine. We also need to send additional money for salaries plus double bonus to Misha (Michael). I have already paid $50k for Engel’s case (20к – forensics, $30к – to speed up the starting of the criminal case)

Stupin: Why have you paid for Engel’s case ? I was even against paying for the Red’s case. Why pay for Engel’s? What is the point?

Gusev: To my mind, you do not fully understand what’s been going on for the last year. Paul has a plan to either throw me into jail or end me. His intentions are totally clear. There are only two choices: 1 – do nothing, and pay nothing to nobody, and at the end either go to jail or keep hiding until all the resources are exhausted; 2 – do the same thing, as he is doing, with the same goal.

Continue reading →

![]() Adobe said one of the bugs, a cross-site scripting flaw, is being exploited in the wild in targeted attacks to trick users into clicking on a malicious link delivered in an email message. At the moment there isn’t much more information about this vulnerability (other than Adobe credits Google with reporting it). That may soon change if news begin to surface about which organizations were targeted with the help of this flaw.

Adobe said one of the bugs, a cross-site scripting flaw, is being exploited in the wild in targeted attacks to trick users into clicking on a malicious link delivered in an email message. At the moment there isn’t much more information about this vulnerability (other than Adobe credits Google with reporting it). That may soon change if news begin to surface about which organizations were targeted with the help of this flaw.