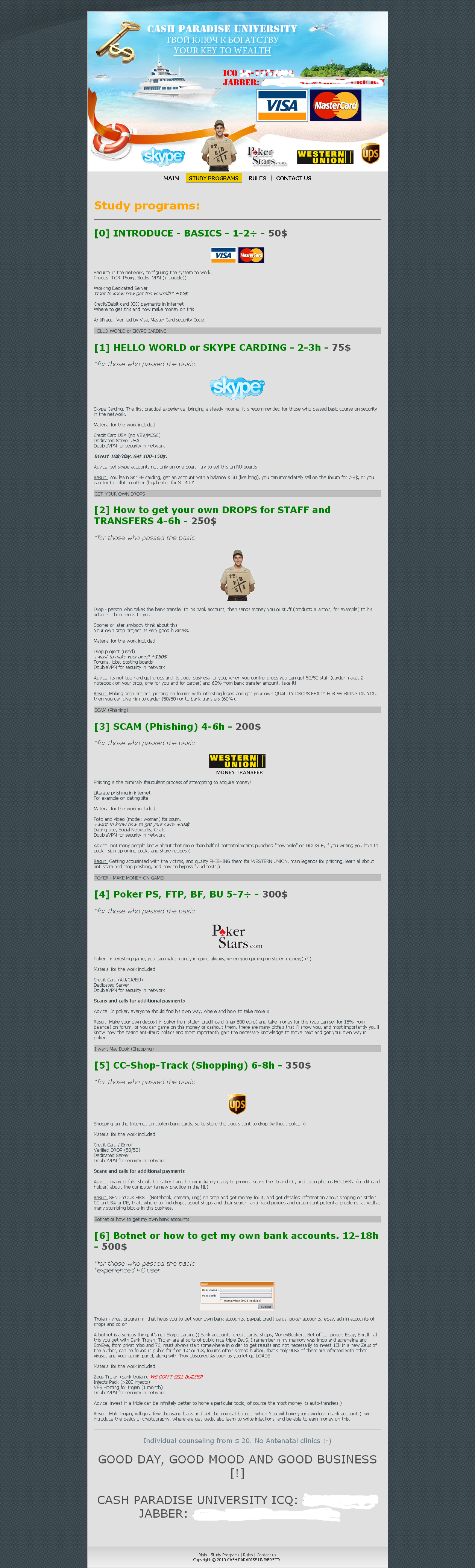

Individuals who normally promote unlicensed, fly-by-night Internet pharmacies recently registered hundreds of hardcore porn and bestiality Web sites using contact information for the founder of a company that has helped to shutter more than 10,000 of these Internet pill mills over the past year, KrebsOnSecurity.com has learned.

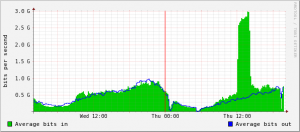

The reputation attack is the latest sortie in an increasingly high-profile and high-stakes battle among spammers, online pill purveyors and those trying to shed light on their activities. Around the same time that these fake domains were registered, KrebsOnSecurity.com came under a sustained denial of service attack that traced back to Russian pill gangs.

In the third week of September, hundreds of domains were registered using the name, phone number and former business address of John Horton, founder of LegitScript, an Internet pharmacy verification service. The domains, many containing the word “adult,” all redirect to a handful of porn and bestiality sites (a partial list is available here, but please tread lightly with these sites because they are definitely not safe for work and may not be safe for your PC).

The sites were registered just days after LegitScript finalized a deal with eNom Inc., the world’s 5th-largest domain name registrar. At the time of that agreement, roughly 40 percent of the unlicensed online pharmacies selling drugs without requiring a prescription were registered through eNom, according to Horton.

Since then, many affiliates who promote pill sites via online pharmacy affiliate programs have been scrambling to move their domains to other registrars, with varying degrees of success.