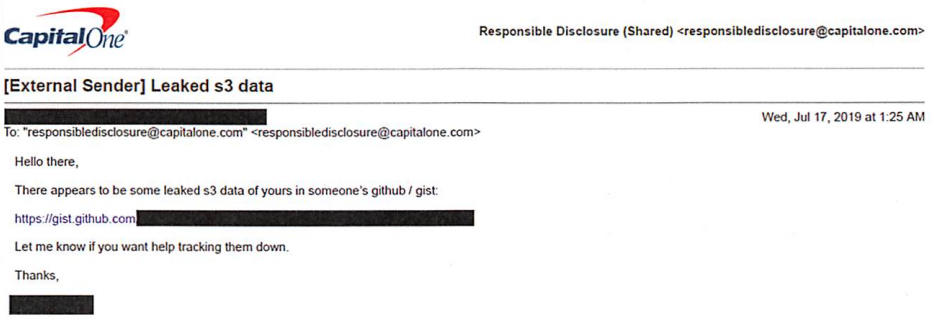

On Monday, a former Amazon employee was arrested and charged with stealing more than 100 million consumer applications for credit from Capital One. Since then, many have speculated the breach was perhaps the result of a previously unknown “zero-day” flaw, or an “insider” attack in which the accused took advantage of access surreptitiously obtained from her former employer. But new information indicates the methods she deployed have been well understood for years.

What follows is based on interviews with almost a dozen security experts, including one who is privy to details about the ongoing breach investigation. Because this incident deals with somewhat jargon-laced and esoteric concepts, much of what is described below has been dramatically simplified. Anyone seeking a more technical explanation of the basic concepts referenced here should explore some of the many links included in this story.

According to a source with direct knowledge of the breach investigation, the problem stemmed in part from a misconfigured open-source Web Application Firewall (WAF) that Capital One was using as part of its operations hosted in the cloud with Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Known as “ModSecurity,” this WAF is deployed along with the open-source Apache Web server to provide protections against several classes of vulnerabilities that attackers most commonly use to compromise the security of Web-based applications.

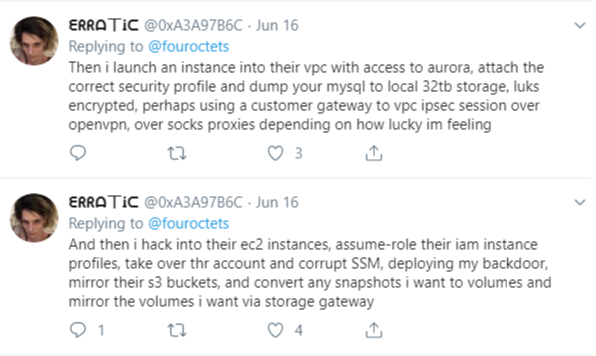

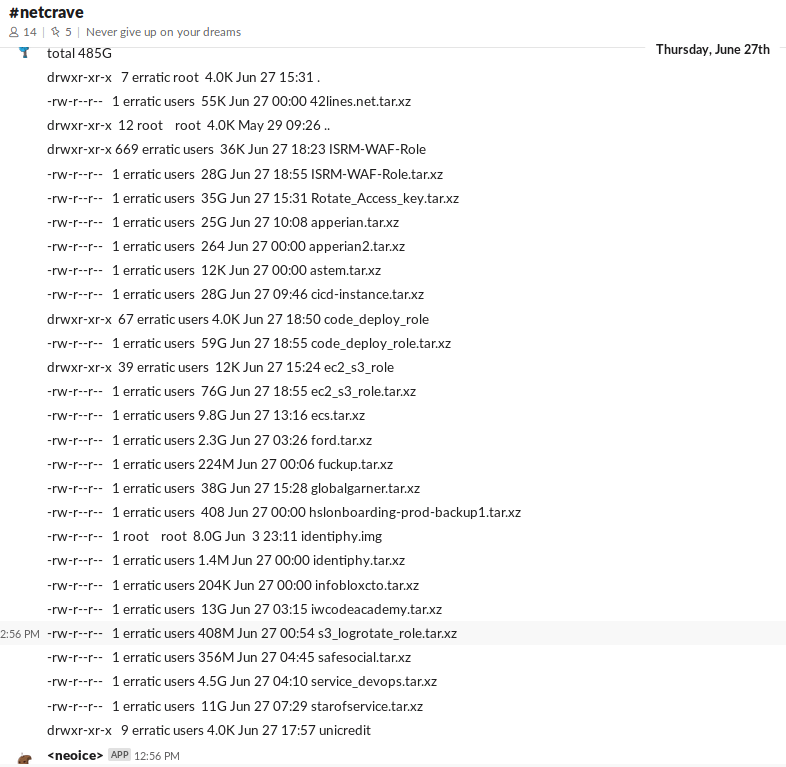

The misconfiguration of the WAF allowed the intruder to trick the firewall into relaying requests to a key back-end resource on the AWS platform. This resource, known as the “metadata” service, is responsible for handing out temporary information to a cloud server, including current credentials sent from a security service to access any resource in the cloud to which that server has access.

In AWS, exactly what those credentials can be used for hinges on the permissions assigned to the resource that is requesting them. In Capital One’s case, the misconfigured WAF for whatever reason was assigned too many permissions, i.e. it was allowed to list all of the files in any buckets of data, and to read the contents of each of those files.

The type of vulnerability exploited by the intruder in the Capital One hack is a well-known method called a “Server Side Request Forgery” (SSRF) attack, in which a server (in this case, CapOne’s WAF) can be tricked into running commands that it should never have been permitted to run, including those that allow it to talk to the metadata service.

Evan Johnson, manager of the product security team at Cloudflare, recently penned an easily digestible column on the Capital One hack and the challenges of detecting and blocking SSRF attacks targeting cloud services. Johnson said it’s worth noting that SSRF attacks are not among the dozen or so attack methods for which detection rules are shipped by default in the WAF exploited as part of the Capital One intrusion.

“SSRF has become the most serious vulnerability facing organizations that use public clouds,” Johnson wrote. “The impact of SSRF is being worsened by the offering of public clouds, and the major players like AWS are not doing anything to fix it. The problem is common and well-known, but hard to prevent and does not have any mitigations built into the AWS platform.”

Johnson said AWS could address this shortcoming by including extra identifying information in any request sent to the metadata service, as Google has already done with its cloud hosting platform. He also acknowledged that doing so could break a lot of backwards compatibility within AWS.

“There’s a lot of specialized knowledge that comes with operating a service within AWS, and to someone without specialized knowledge of AWS, [SSRF attacks are] not something that would show up on any critical configuration guide,” Johnson said in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity.

“You have to learn how EC2 works, understand Amazon’s Identity and Access Management (IAM) system, and how to authenticate with other AWS services,” he continued. “A lot of people using AWS will interface with dozens of AWS services and write software that orchestrates and automates new services, but in the end people really lean into AWS a ton, and with that comes a lot of specialized knowledge that is hard to learn and hard to get right.”

In a statement provided to KrebsOnSecurity, Amazon said it is inaccurate to argue that the Capital One breach was caused by AWS IAM, the instance metadata service, or the AWS WAF in any way.

“The intrusion was caused by a misconfiguration of a web application firewall and not the underlying infrastructure or the location of the infrastructure,” the statement reads. “AWS is constantly delivering services and functionality to anticipate new threats at scale, offering more security capabilities and layers than customers can find anywhere else including within their own datacenters, and when broadly used, properly configured and monitored, offer unmatched security—and the track record for customers over 13+ years in securely using AWS provides unambiguous proof that these layers work.”

Amazon pointed to several (mostly a la carte) services it offers AWS customers to help mitigate many of the threats that were key factors in this breach, including:

–Access Advisor, which helps identify and scope down AWS roles that may have more permissions than they need;

–GuardDuty, designed to raise alarms when someone is scanning for potentially vulnerable systems or moving unusually large amounts of data to or from unexpected places;

–The AWS WAF, which Amazon says can detect common exploitation techniques, including SSRF attacks;

–Amazon Macie, designed to automatically discover, classify and protect sensitive data stored in AWS.

William Bengston, formerly a senior security engineer at Netflix, wrote a series of blog posts last year on how Netflix built its own systems for detecting and preventing credential compromises in AWS. Interestingly, Bengston was hired roughly two months ago to be director of cloud security for Capital One. My guess is Capital One now wishes they had somehow managed to lure him away sooner. Continue reading →