The U.S. government — along with a number of leading security companies — recently warned about a series of highly complex and widespread attacks that allowed suspected Iranian hackers to siphon huge volumes of email passwords and other sensitive data from multiple governments and private companies. But to date, the specifics of exactly how that attack went down and who was hit have remained shrouded in secrecy.

This post seeks to document the extent of those attacks, and traces the origins of this overwhelmingly successful cyber espionage campaign back to a cascading series of breaches at key Internet infrastructure providers.

Before we delve into the extensive research that culminated in this post, it’s helpful to review the facts disclosed publicly so far. On Nov. 27, 2018, Cisco’s Talos research division published a write-up outlining the contours of a sophisticated cyber espionage campaign it dubbed “DNSpionage.”

The DNS part of that moniker refers to the global “Domain Name System,” which serves as a kind of phone book for the Internet by translating human-friendly Web site names (example.com) into numeric Internet address that are easier for computers to manage.

Talos said the perpetrators of DNSpionage were able to steal email and other login credentials from a number of government and private sector entities in Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates by hijacking the DNS servers for these targets, so that all email and virtual private networking (VPN) traffic was redirected to an Internet address controlled by the attackers.

Talos reported that these DNS hijacks also paved the way for the attackers to obtain SSL encryption certificates for the targeted domains (e.g. webmail.finance.gov.lb), which allowed them to decrypt the intercepted email and VPN credentials and view them in plain text.

On January 9, 2019, security vendor FireEye released its report, “Global DNS Hijacking Campaign: DNS Record Manipulation at Scale,” which went into far greater technical detail about the “how” of the espionage campaign, but contained few additional details about its victims.

About the same time as the FireEye report, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a rare emergency directive ordering all U.S. federal civilian agencies to secure the login credentials for their Internet domain records. As part of that mandate, DHS published a short list of domain names and Internet addresses that were used in the DNSpionage campaign, although those details did not go beyond what was previously released by either Cisco Talos or FireEye.

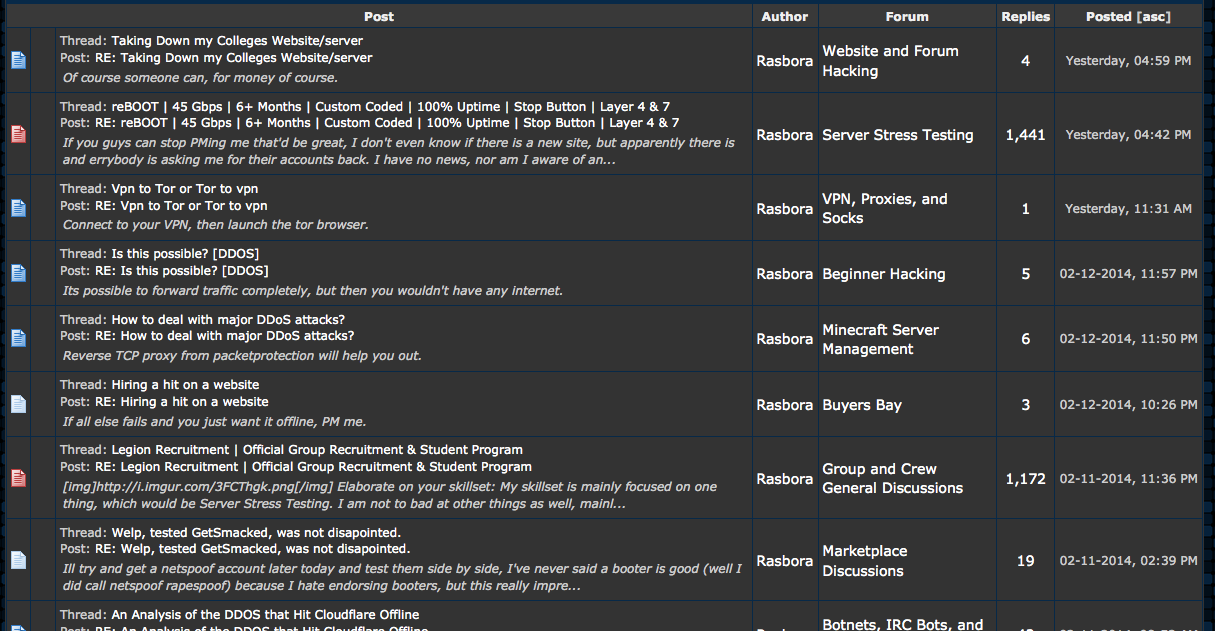

That changed on Jan. 25, 2019, when security firm CrowdStrike published a blog post listing virtually every Internet address known to be (ab)used by the espionage campaign to date. The remainder of this story is based on open-source research and interviews conducted by KrebsOnSecurity in an effort to shed more light on the true extent of this extraordinary — and ongoing — attack.

The “indicators of compromise” related to the DNSpionage campaign, as published by CrowdStrike.

PASSIVE DNS

I began my research by taking each of the Internet addresses laid out in the CrowdStrike report and running them through both Farsight Security and SecurityTrails, services that passively collect data about changes to DNS records tied to tens of millions of Web site domains around the world.

Working backwards from each Internet address, I was able to see that in the last few months of 2018 the hackers behind DNSpionage succeeded in compromising key components of DNS infrastructure for more than 50 Middle Eastern companies and government agencies, including targets in Albania, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

For example, the passive DNS data shows the attackers were able to hijack the DNS records for mail.gov.ae, which handles email for government offices of the United Arab Emirates. Here are just a few other interesting assets successfully compromised in this cyber espionage campaign:

-nsa.gov.iq: the National Security Advisory of Iraq

-webmail.mofa.gov.ae: email for the United Arab Emirates’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs

-shish.gov.al: the State Intelligence Service of Albania

-mail.mfa.gov.eg: mail server for Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs

-mod.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Defense

-embassy.ly: Embassy of Libya

-owa.e-albania.al: the Outlook Web Access portal for the e-government portal of Albania

-mail.dgca.gov.kw: email server for Kuwait’s Civil Aviation Bureau

-gid.gov.jo: Jordan’s General Intelligence Directorate

-adpvpn.adpolice.gov.ae: VPN service for the Abu Dhabi Police

-mail.asp.gov.al: email for Albanian State Police

-owa.gov.cy: Microsoft Outlook Web Access for Government of Cyprus

-webmail.finance.gov.lb: email for Lebanon Ministry of Finance

-mail.petroleum.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Petroleum

-mail.cyta.com.cy: Cyta telecommunications and Internet provider, Cyprus

-mail.mea.com.lb: email access for Middle East Airlines

The passive DNS data provided by Farsight and SecurityTrails also offered clues about when each of these domains was hijacked. In most cases, the attackers appear to have changed the DNS records for these domains (we’ll get to the “how” in a moment) so that the domains pointed to servers in Europe that they controlled.

Shortly after the DNS records for these TLDs were hijacked — sometimes weeks, sometimes just days or hours — the attackers were able to obtain SSL certificates for those domains from SSL providers Comodo and/or Let’s Encrypt. The preparation for several of these attacks can be seen at crt.sh, which provides a searchable database of all new SSL certificate creations.

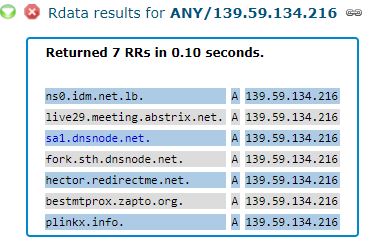

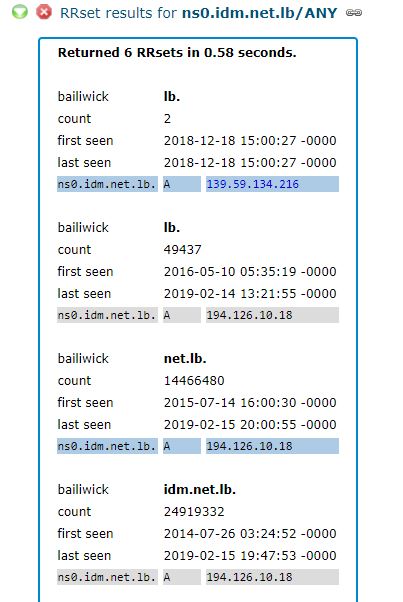

Let’s take a closer look at one example. The CrowdStrike report references the Internet address 139.59.134[.]216 (see above), which according to Farsight was home to just seven different domains over the years. Two of those domains only appeared at that Internet address in December 2018, including domains in Lebanon and — curiously — Sweden.

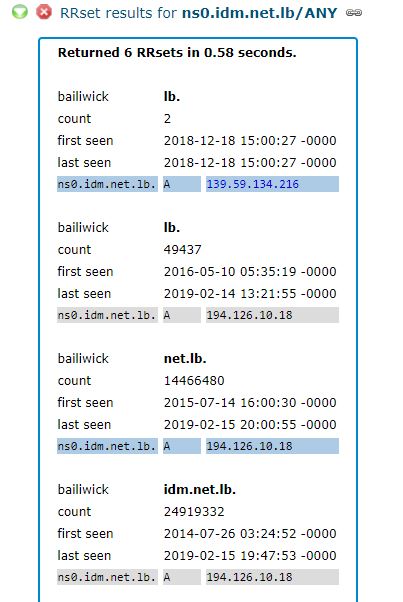

The first domain was “ns0.idm.net.lb,” which is a server for the Lebanese Internet service provider IDM. From early 2014 until December 2018, ns0.idm.net.lb pointed to 194.126.10[.]18, which appropriately enough is an Internet address based in Lebanon. But as we can see in the screenshot from Farsight’s data below, on Dec. 18, 2018, the DNS records for this ISP were changed to point Internet traffic destined for IDM to a hosting provider in Germany (the 139.59.134[.]216 address).

Source: Farsight Security

Notice what else is listed along with IDM’s domain at 139.59.134[.]216, according to Farsight:

The DNS records for the domains sa1.dnsnode.net and fork.sth.dnsnode.net also were changed from their rightful home in Sweden to the German hosting provider controlled by the attackers in December. These domains are owned by Netnod Internet Exchange, a major global DNS provider based in Sweden. Netnod also operates one of the 13 “root” name servers, a critical resource that forms the very foundation of the global DNS system.

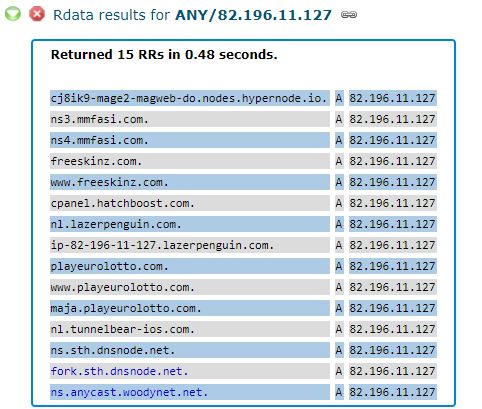

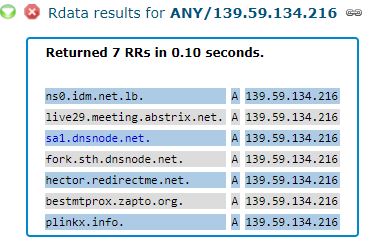

We’ll come back to Netnod in a moment. But first let’s look at another Internet address referenced in the CrowdStrike report as part of the infrastructure abused by the DNSpionage hackers: 82.196.11[.]127. This address in The Netherlands also is home to the domain mmfasi[.]com, which Crowdstrike says was one of the attacker’s domains that was used as a DNS server for some of the hijacked infrastructure.

As we can see in the screenshot above, 82.196.11[.]127 was temporarily home to another pair of Netnod DNS servers, as well as the server “ns.anycast.woodynet.net.” That domain is derived from the nickname of Bill Woodcock, who serves as executive director of Packet Clearing House (PCH).

PCH is a nonprofit entity based in northern California that also manages significant amounts of the world’s DNS infrastructure, particularly the DNS for more than 500 top-level domains and a number of the Middle East top-level domains targeted by DNSpionage. Continue reading →

Some 20 of the flaws addressed in February’s update bundle are weaknesses labeled “critical,” meaning Microsoft believes that attackers or malware could exploit them to fully compromise systems through little or no help from users — save from convincing a user to visit a malicious or hacked Web site.

Some 20 of the flaws addressed in February’s update bundle are weaknesses labeled “critical,” meaning Microsoft believes that attackers or malware could exploit them to fully compromise systems through little or no help from users — save from convincing a user to visit a malicious or hacked Web site.