Most people who have frozen their credit files with Equifax have been issued a numeric Personal Identification Number (PIN) which is supposed to be required before a freeze can be lifted or thawed. Unfortunately, if you don’t already have an account at the credit bureau’s new myEquifax portal, it may be simple for identity thieves to lift an existing credit freeze at Equifax and bypass the PIN armed with little more than your, name, Social Security number and birthday.

Consumers in every U.S. state can now freeze their credit files for free with Equifax and two other major bureaus (Trans Union and Experian). A freeze makes it much harder for identity thieves to open new lines of credit in your name.

In the wake of Equifax’s epic 2017 data breach impacting some 148 million Americans, many people did freeze their credit files at the big three in response. But Equifax has changed a few things since then.

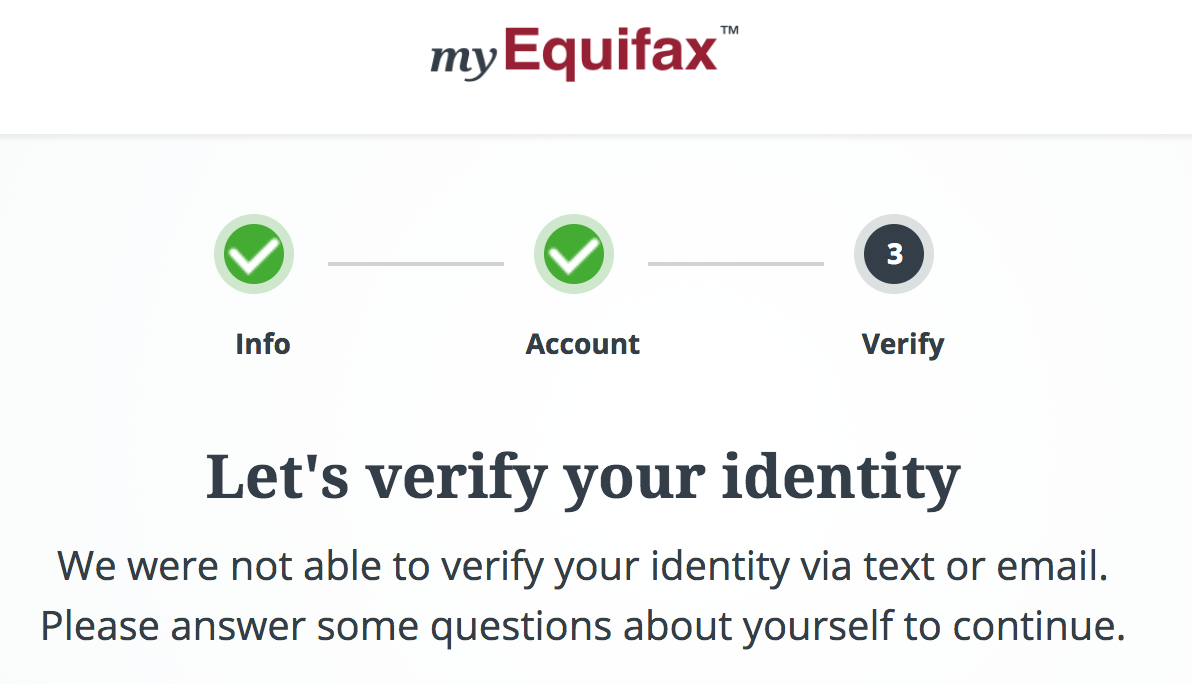

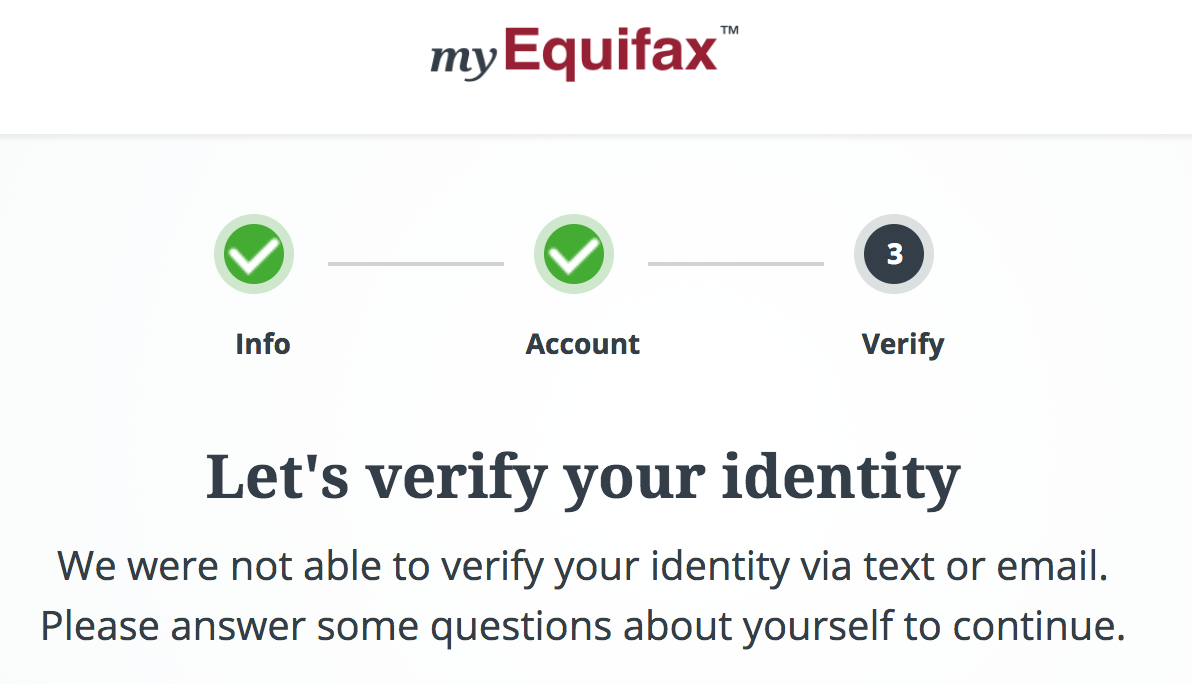

Seeking to manage my own credit freeze at equifax.com as I’d done in years past, I was steered toward creating an account at myequifax.com, which I was shocked to find I did not previously possess.

Getting an account at myequifax.com was easy. In fact, it was too easy. The portal asked me for an email address and suggested a longish, randomized password, which I accepted. I chose an old email address that I knew wasn’t directly tied to my real-life identity.

The next page asked me enter my SSN and date of birth, and to share a phone number (sharing was optional, so I didn’t). SSN and DOB data is widely available for sale in the cybercrime underground on almost all U.S. citizens. This has been the reality for years, and was so well before Equifax announced its big 2017 breach.

myEquifax said it couldn’t verify that my email address belonged to the Brian Krebs at that SSN and DOB. It then asked a series of four security questions — so-called “knowledge-based authentication” or KBA questions designed to see if I could recall bits about my recent financial history.

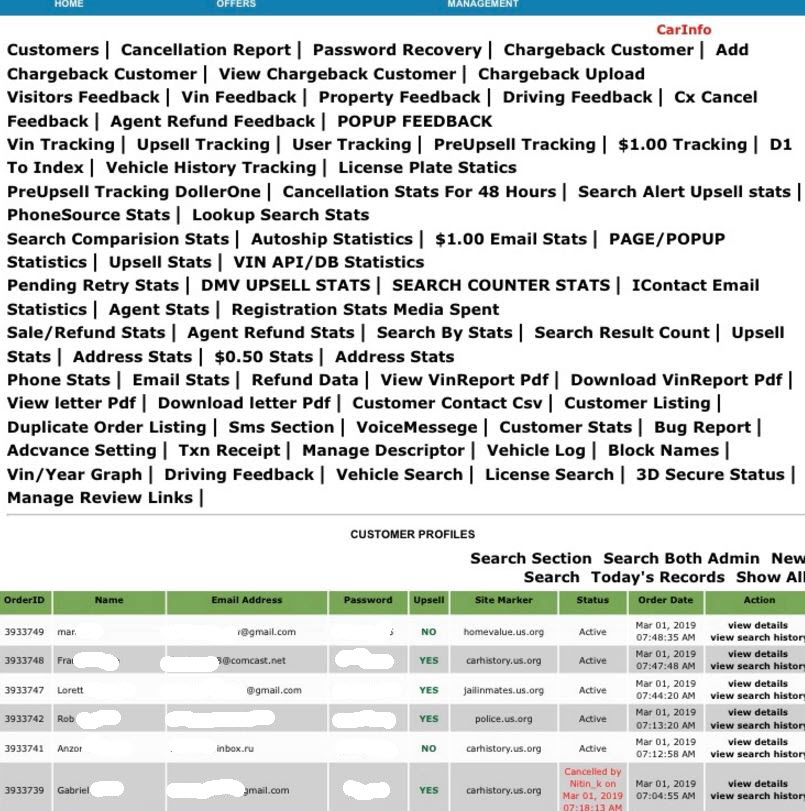

In general, the data being asked about in these KBA quizzes is culled from public records, meaning that this information likely is publicly available in some form — either digitally or in-person. Indeed, I have long assailed the KBA industry as creating a false sense of security that is easily bypassed by fraudsters.

One potential problem with relying on KBA questions to authenticate consumers online is that so much of the information needed to successfully guess the answers to those multiple-choice questions is now indexed or exposed by search engines, social networks and third-party services online — both criminal and commercial.

The first three multiple-guess questions myEquifax asked were about loans or debts that I have never owed. Thus, the answer to the first three KBA questions asked was, “none of the above.” The final question asked for the name of our last mortgage company. Again, information that is not hard to find.

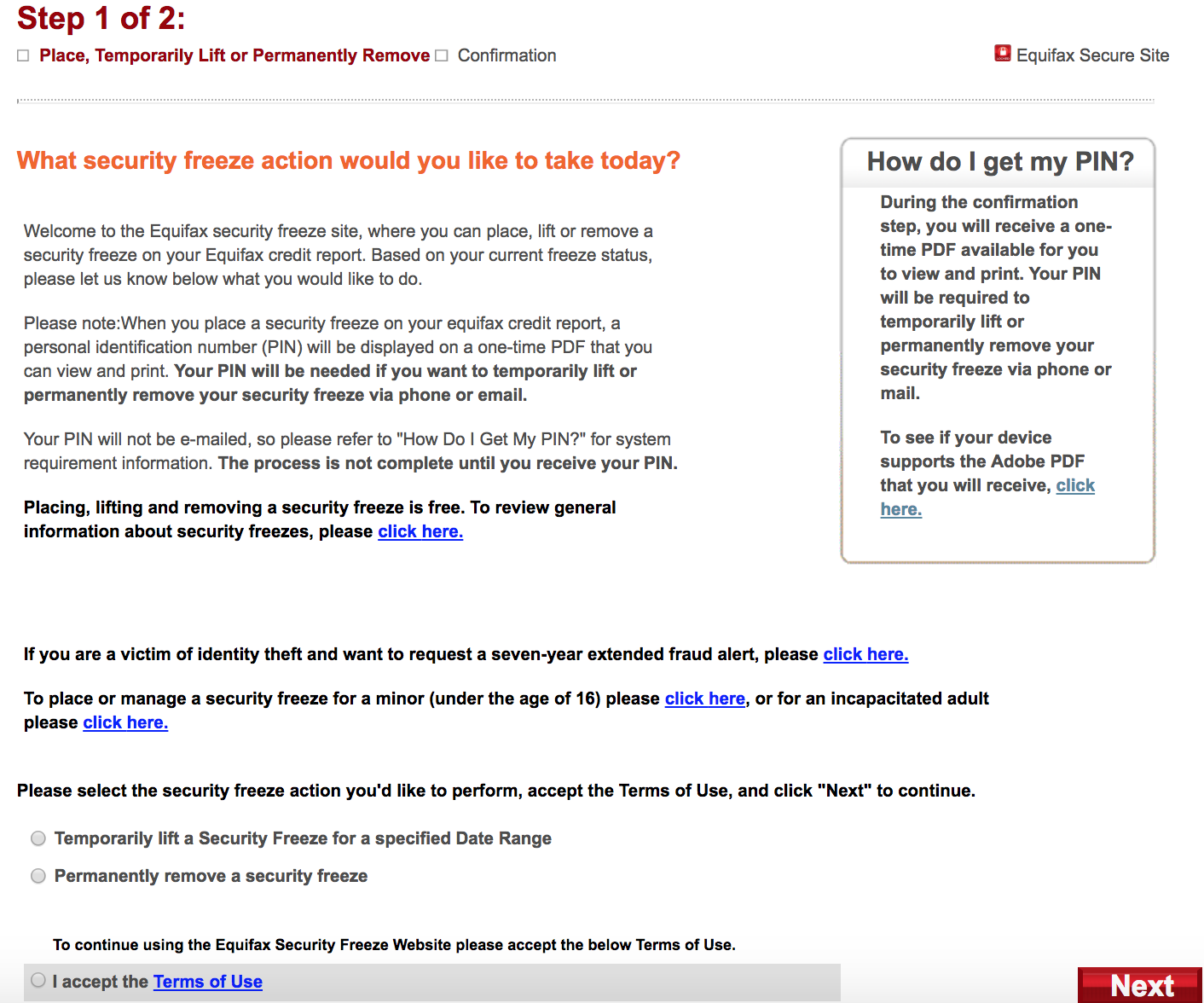

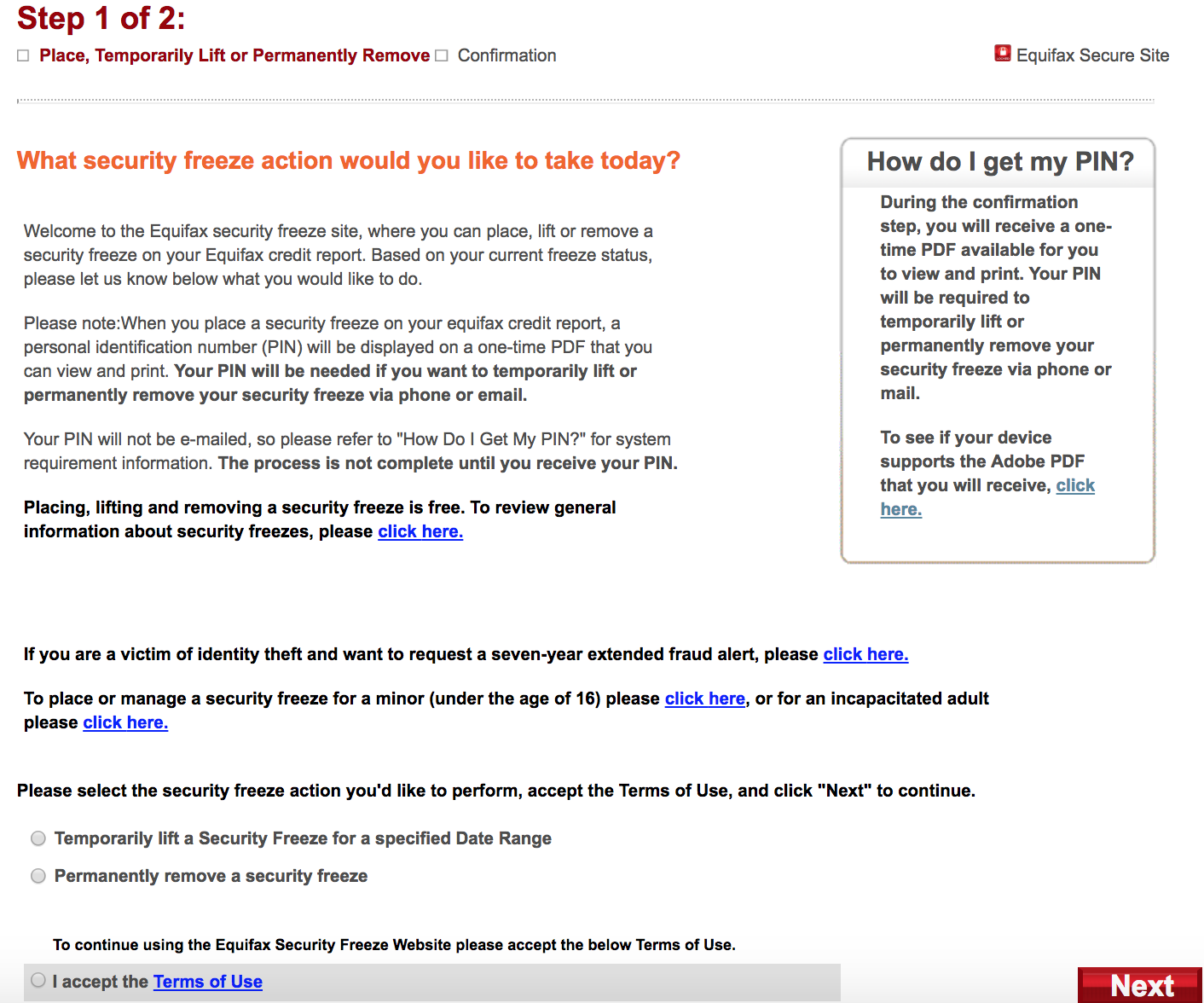

Satisfied with my answers, Equifax informed me that yes indeed I was Brian Krebs and that I could now manage my existing freeze with the company. After requesting a thaw, I was brought to a vintage Equifax page that looked nothing like myEquifax’s sunnier new online plumage.

Equifax’s site says it will require users requesting changes to an existing credit freeze to have access to their freeze PIN and be ready to supply it. But Equifax never actually asks for the PIN.

This page informed me that if I previously secured a freeze of my credit file with Equifax and been given a PIN needed to undo that status in any way, that I should be ready to provide said information if I was requesting changes via phone or email.

In other words, credit freezes and thaws requested via myEquifax don’t require users to supply any pre-existing PIN.

Fine, I said. Let’s do this.

myEquifax then asked for the date range requested to thaw my credit freeze. Submit.

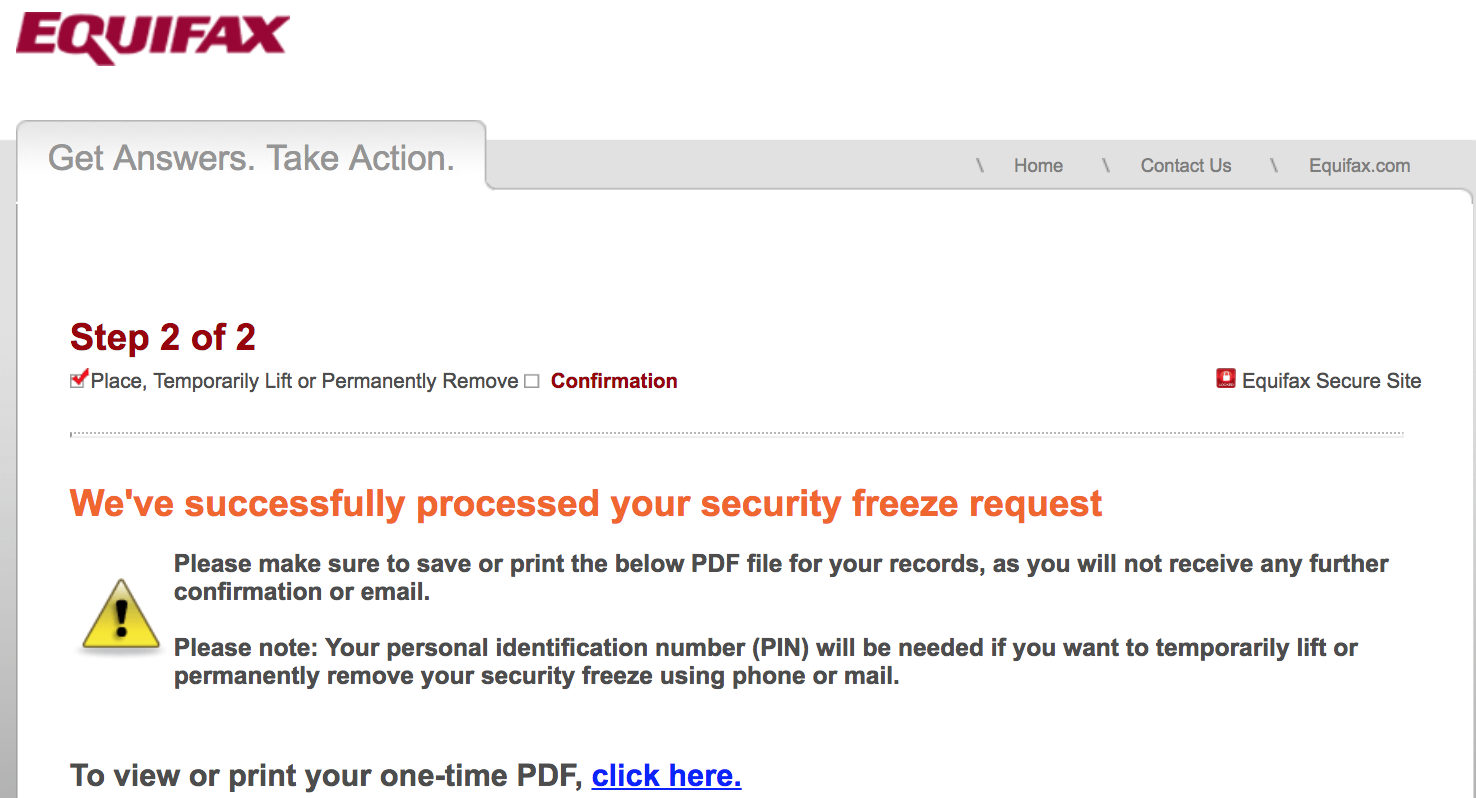

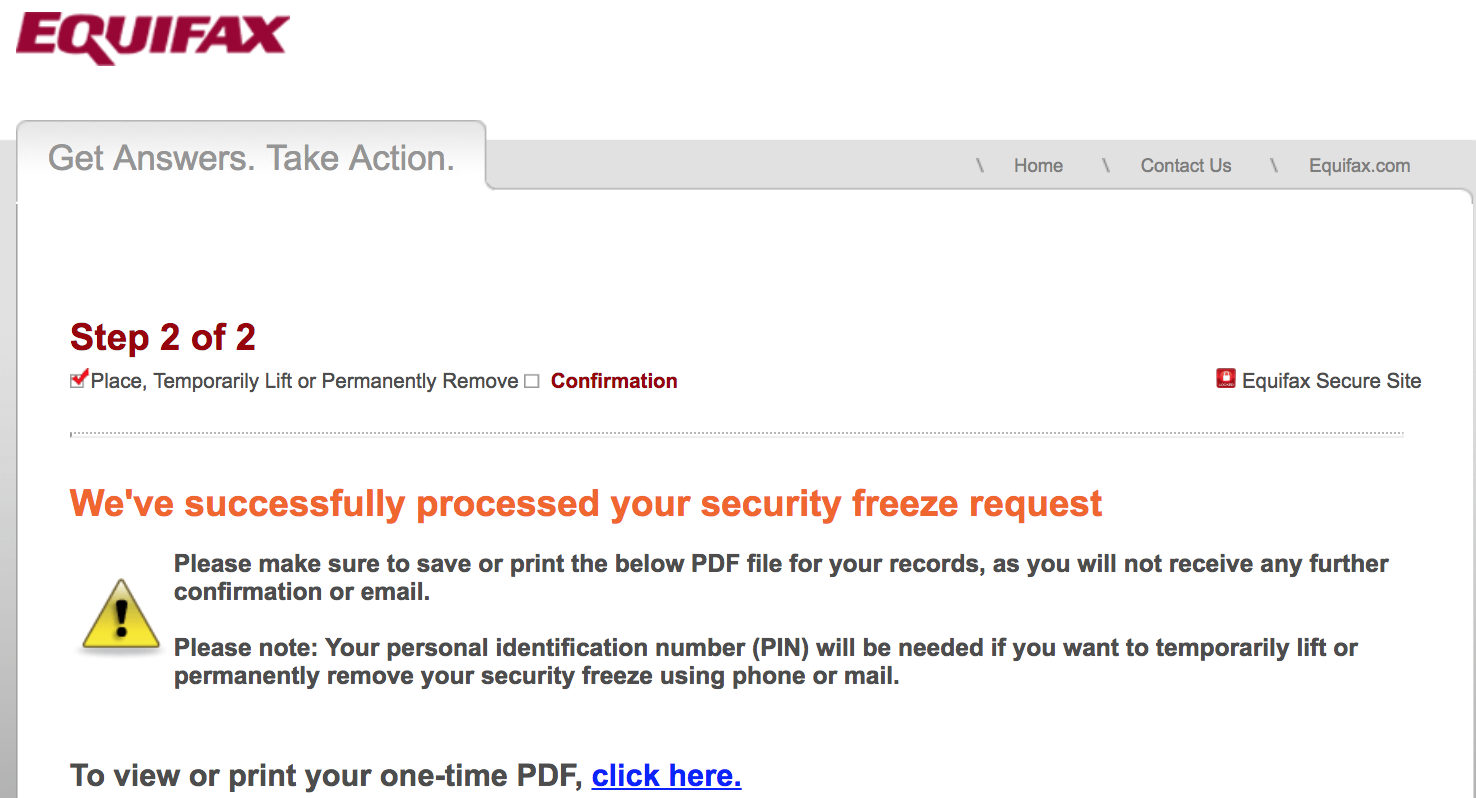

“We’ve successfully processed your security freeze request!,” the site declared.

This also was exclaimed in an email to the random old address I’d used at myEquifax, although the site never once made any attempt to validate that I had access to this inbox, something that could be done by simply sending a confirmation link that needs to be clicked to activate the account.

In addition, I noticed Equifax added my old mobile number to my account, even though I never supplied this information and was not using this phone when I created the myEquifax account.

Successfully unfreezing (temporarily thawing) my credit freeze did not require me to ever supply my previously-issued freeze PIN from Equifax. Anyone who knew the vaguest and most knowable details about me could have done the same.

myEquifax.com does not currently seek to verify the account by requesting confirmation via a phone call or text to the phone number associated with the account (also, recall that even providing a phone number was optional).

Happily, I did discover then when I used a different computer and Internet address to try to open up another account under my name, date of birth and SSN, it informed me that a profile already existed for this information. This suggests that signing up at myEquifax is probably a good idea, given that the alternative is more risky.

It was way too easy to create my account, but I’m not saying everyone will be able to create one online. In testing with several readers over the past 24 hours, myEquifax seems to be returning a lot more error pages at the KBA stage of the process now, prompting people to try again later or make a request via email or phone.

Equifax spokesperson Nancy Bistritz-Balkan said not requiring a PIN for people with existing freezes was by design.

“With myEquifax, we created an online experience that enables consumers to securely and conveniently manage security freezes and fraud alerts,” Bistritz-Balkan said..

“We deployed an experience that embraces both security standards (using a multi-factor and layered approach to verify the consumer’s identity) and reflects specific consumer feedback on managing security freezes and fraud alerts online without the use of a PIN,” she continued. “The account set-up process, which involves the creation of a username and password, relies on both user inputs and other factors to securely establish, verify, and authenticate that the consumer’s identity is connected to the consumer every time.” Continue reading →

One interesting patch from Microsoft this week comes in response to a

One interesting patch from Microsoft this week comes in response to a