Maybe you’ve been feeling left out because you weren’t among the lucky few hundred million or billion who had their personal information stolen in either the Equifax or Yahoo! breaches. Well buck up, camper: Both companies took steps to make you feel better today.

Yahoo! announced that, our bad!: It wasn’t just one billion users who had their account information filched in its record-breaking 2013 data breach. It was more like three billion (read: all) users. Meanwhile, big three credit bureau Equifax added 2.5 million more victims to its roster of 143 million Americans who had their Social Security numbers and other personal data stolen in a breach earlier this year. At the same time, Equifax’s erstwhile CEO informed Congress that the breach was the result of even more bone-headed security than was first disclosed.

To those still feeling left out by either company after this spate of bad news, I have only one thing to say (although I feel a bit like a broken record in repeating this): Assume you’re compromised, and take steps accordingly.

If readers are detecting a bit of sarcasm and cynicism in my tone here, it may be that I’m still wishing I’d done almost anything else today besides watching three hours worth of testimony from former Equifax CEO Richard Smith before lawmakers on a panel of the House Energy & Commerce Committee.

While he is no longer the boss of Equifax, Smith gamely agreed to submit to several day’s worth of grilling from legislators in both houses of Congress this week. It was clear from the questions that lawmakers didn’t ask in Round One, however, that Smith was far more prepared for the first batch of questioning than they were, and that the entire ordeal would amount to only a gentle braising.

Nevertheless, Smith managed to paint an even more dismal picture than was already known about the company’s failures to secure the very data that makes up the core of its business. Helpfully, Smith clarified early on in the hearing that the company’s customers are in fact banks and other businesses — not consumers.

Smith told lawmakers that the breach stemmed from a combination of technological error and a human error, casting it as the kind of failure that could have happened to anyone. In reality, the company waited 4.5 months (after it discovered the breach in late July 2017) to fix a dangerous security flaw that it should have known was being exploited on Day One (~March 6 or 7, 2017).

“The human error involved the failure to apply a software patch to a dispute portal in March 2017,” Smith said. He declined to explain (and lawmakers inexplicably failed to ask) how 145.5 million Americans — nearly 60 percent of the adult population of the United States — could have had their information tied up in a dispute portal at Equifax. “The technological error involved a scanner which failed to detect a vulnerability on that particular portal.”

As noted in this Wired.com story, Smith admitted that the data compromised in the breach was not encrypted:

When asked by representative Adam Kinzinger of Illinois about what data Equifax encrypts in its systems, Smith admitted that the data compromised in the customer-dispute portal was stored in plaintext and would have been easily readable by attackers. “We use many techniques to protect data—encryption, tokenization, masking, encryption in motion, encrypting at rest,” Smith said. “To be very specific, this data was not encrypted at rest.”

It’s unclear exactly what of the pilfered data resided in the portal versus other parts of Equifax’s system, but it turns out that also didn’t matter much, given Equifax’s attitude toward encryption overall. “OK, so this wasn’t [encrypted], but your core is?” Kinzinger asked. “Some, not all,” Smith replied. “There are varying levels of security techniques that the team deploys in different environments around the business.”

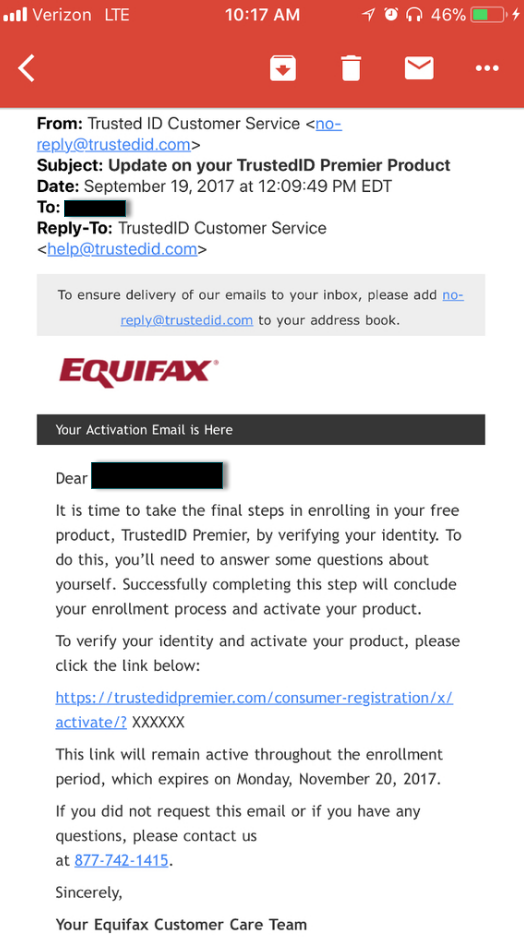

Smith also sought to justify the company’s historically poor breach response after it publicly disclosed the break-in on Sept. 7 — roughly 40 days after Equifax’s security team first became aware of the incident (on July 29). As many readers here are well familiar, KrebsOnSecurity likened that breach response to a dumpster fire — noting that it was perhaps the most haphazard and ill-conceived of any major data breach disclosure in history.

Smith artfully dodged questions of why the company waited so long to notify the public, and about the perception that Equifax sought to profit off of its own data breach. One lawmaker noted that Smith gave two public speeches in the second and third weeks of August in which he was quoted as saying that fraud was a “a huge opportunity for Equifax,” and that it was a “massive, growing business” for the company.

Smith interjected that he had “no indication” that consumer data was compromised at the time of the Aug. 11 speech. As for the Aug. 17 address, he said “we did not know how much data was compromised, what data was compromised.”

Follow-up questions from lawmakers on the panel revealed that Smith didn’t ask for a briefing about what was then allegedly only classified internally as “suspicious activity” until August 15, almost two weeks after the company hired outside cybersecurity experts to examine the issue.

Smith also maneuvered around questions about why Equifax chose to disclose the breach on the very day that Hurricane Irma was dominating front-page news with an imminent landfall on the eastern seaboard of the United States.

However, Smith did blame Irma in explaining why the company’s phone systems were simply unable to handle the call volume from U.S. consumers concerned about the Category Five data breach, saying that Irma took down two of Equifax’s largest call centers days after the breach disclosure. He said the company handled over 420 million consumer visits to the portal designed to help people figure out whether they were victimized in the breach, underscoring how so many American adults were forced to revisit the site again and again because it failed to give people consistent answers about whether they were affected. Continue reading

In

In