When you’re planning to rob the Russian cyber mob, you’d better make sure that you have the element of surprise, that you can make a clean getaway, and that you understand how your target is going to respond. Today’s column features an interview with two security experts who helped plan and execute last week’s global, collaborative effort to hijack the Gameover Zeus botnet, an extremely resilient and sophisticated crime machine that helped an elite group of thieves steal more than $100 million from banks, businesses and consumers worldwide.

Neither expert I spoke with wished to be identified for this story, citing a lack of permission from their employers and a desire to remain off the radar of the crooks inconvenienced by the action. For obvious reasons, they were also reluctant to share details about the exact weaknesses that were used to hijack the botnet, focusing instead on the planning and and preparation that went into this effort.

GAMEOVER ZEUS PRIMER

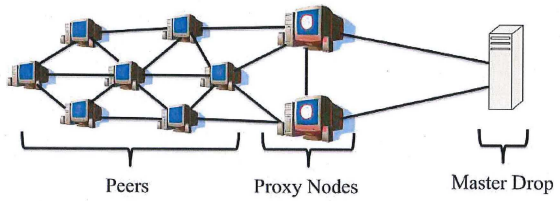

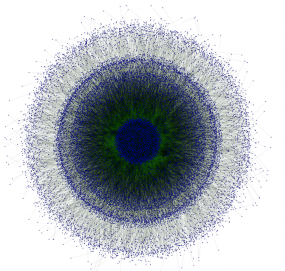

A quick review of how Gameover works should help readers get more out of the interview. In traditional botnets, infected PCs report home to and are controlled by a central server. But this architecture leaves such botnets vulnerable to disruption or takeover if authorities or security experts can gain access to the control server.

Gameover, on the other hand, is a peer-to-peer (P2P) botnet designed as a collection of small networks that are distinct but linked up in a decentralized fashion. The individual Gameover-infected PCs are known as “peers.” Above the peers are a select number of slightly more powerful and important infected systems that are assigned roles as “proxy nodes,” meaning they were selected from the peers to serve as relay points for commands coming from the Gameover botnet operators and as conduits for encrypted data stolen from the infected systems.

The Gameover botnet code also includes a failsafe mechanism that can be invoked if the botnet’s P2P communications system fails, whether the failure is the result of a faulty malware update or because of a takedown effort by researchers/law enforcement. That failsafe is a domain generation algorithm (DGA) component that generates a list of 1,000 domain names each week (gibberish domains that are essentially long jumbles of letters) combined with one of six top-level domains; .com, .net, .org, .biz, .info and .ru. In the event the infected Gameover systems can’t get new instructions from their peers, the code instructs the botted systems to seek out domains from the latest list of 1,000 domains generated by the DGA until it finds a site with new instructions.

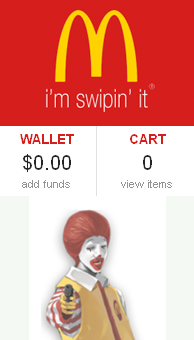

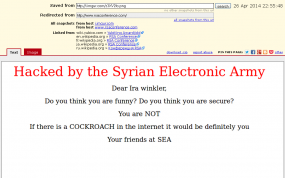

HUNDREDS OF ‘WEB INJECTS’

The Gameover malware was designed specifically to defeat two-factor authentication used by many banks. It did so using a huge collection of custom-made scripts known as “Web injects” that can inject custom content into a Web browser when the victim browses to certain sites — such as a specific bank’s login page. Web injects also are used to prompt the victim to enter additional personal information when they log in to a trusted site. An example of this type of Web inject can be seen in the video below, which shows an inject designed for Citibank customers. Continue reading