Adobe today pushed out an emergency update that fixes at least two zero-day vulnerabilities in its ubiquitous Flash Player software — flaws that attackers are already exploiting to break into systems. Interestingly, Adobe warns that one of the exploits in use is designed to drop malware on both Windows and Mac OS X systems.

Adobe said in an advisory that one of the vulnerabilities — CVE-2013-0634 – is being exploited in the wild in attacks delivered via malicious Flash content hosted on websites that target Flash Player in Firefox or Safari on the Macintosh platform, as well as attacks designed to trick Windows users into opening a Microsoft Word document delivered as an email attachment.

Adobe said in an advisory that one of the vulnerabilities — CVE-2013-0634 – is being exploited in the wild in attacks delivered via malicious Flash content hosted on websites that target Flash Player in Firefox or Safari on the Macintosh platform, as well as attacks designed to trick Windows users into opening a Microsoft Word document delivered as an email attachment.

Adobe also warned that a separate flaw — CVE-2013-0633 — is being exploited in the wild in targeted attacks designed to trick the user into opening a Microsoft Word document delivered as an email attachment which contains malicious Flash content. The company said the exploit for CVE-2013-0633 targets the ActiveX version of Flash Player on Windows (i.e. Internet Explorer users).

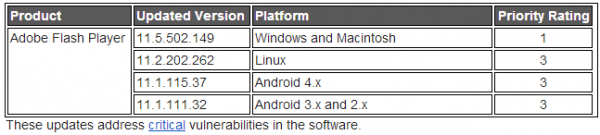

Updates are available for Windows, Mac, Linux and Android users. The latest Windows and Mac version is v. 11.5.502.149, and is available from this link. Those who prefer a direct link to the OS-specific downloads can grab them here. To find out if you have Flash installed and what version your browser may be running, check out this page.

Flash Player installed with Google Chrome should automatically be updated to the latest Google Chrome version, which will include Adobe Flash Player v. 11.5.31.139 for Windows, Macintosh and Linux. Likewise, Internet Explorer 10 for Windows 8 also includes an auto-update feature, which should bring Flash to version 11.3.379.14 for Windows.

Adobe’s advisory notes that the vulnerability that has been used to attack both Mac and Windows users was reported with the help of the Shadowserver Foundation, the federally funded technology research center MITRE Corporation, and aerospace giant Lockheed Martin‘s computer incident response team. No doubt there are some interesting stories about how these attacks were first discovered, and against whom they were initially deployed.