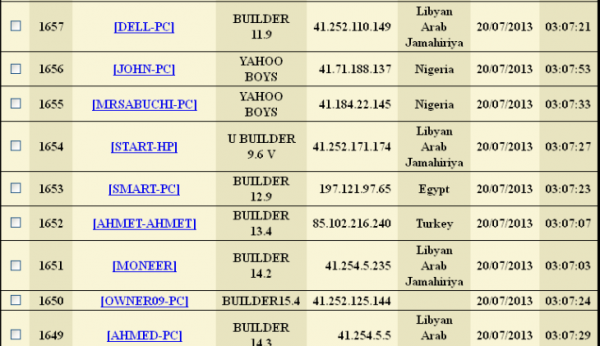

Internet regulators are pushing a controversial plan to restrict public access to WHOIS Web site registration records. Proponents of the proposal say it would improve the accuracy of WHOIS data and better protect the privacy of people who register domain names. Critics argue that such a shift would be unworkable and make it more difficult to combat phishers, spammers and scammers.

A working group within The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the organization that oversees the Internet’s domain name system, has proposed scrapping the current WHOIS system — which is inconsistently managed by hundreds of domain registrars and allows anyone to query Web site registration records. To replace the current system, the group proposes creating a more centralized WHOIS lookup system that is closed by default.

A working group within The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the organization that oversees the Internet’s domain name system, has proposed scrapping the current WHOIS system — which is inconsistently managed by hundreds of domain registrars and allows anyone to query Web site registration records. To replace the current system, the group proposes creating a more centralized WHOIS lookup system that is closed by default.

According to an interim report (PDF) by the ICANN working group, the WHOIS data would be accessible only to “authenticated requestors that are held accountable for appropriate use” of the information.

“After working through a broad array of use cases, and the myriad of issues they raised, [ICANN’s working group] concluded that today’s WHOIS model—giving every user the same anonymous public access to (too often inaccurate) registration data—should be abandoned,” ICANN’s “expert working group” wrote. The group said it “recognizes the need for accuracy, along with the need to protect the privacy of those registrants who may require heightened protections of their personal information.”

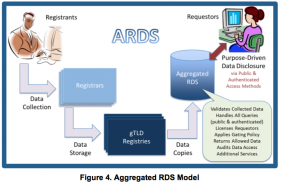

The working group’s current plan envisions creating what it calls an “aggregated registration directory service” (ARDS) to serve as a clearinghouse that contains a non-authoritative copy of all of the collected data elements. The registrars and registries that operate the hundreds of different generic top-level domains (gTLDs, like dot-biz, dot-name, e.g.) would be responsible for maintaining the authoritative sources of WHOIS data for domains in their gTLDs. Those who wish to query WHOIS domain registration data from the system would have to apply for access credentials to the ARDS, which would be responsible for handling data accuracy complaints, auditing access to the system to minimize abuse, and managing the licensing arrangement for access to the WHOIS data.

The plan acknowledges that creating a “one-stop shop” for registration data also might well paint a giant target on the group for hackers, but it holds that such a system would nevertheless allow for greater accountability for validating registration data.

Unsurprisingly, the interim proposal has met with a swell of opposition from some security and technology experts who worry about the plan’s potential for harm to consumers and cybercrime investigators.

“Internet users (individuals, businesses, law enforcement, governments, journalists and others) should not be subject to barriers – including prior authorization, disclosure obligations, payment of fees, etc. – in order to gain access to information about who operates a website, with the exception of legitimate privacy protection services,” reads a letter (PDF) jointly submitted to ICANN last month by G2 Web Services, OpSec Security, LegitScript and DomainTools.

“Internet users have the right to know who is operating a website they are visiting (or, the fact that it is registered anonymously),” the letter continues. “Today, individuals review full WHOIS records and, based on any one of the fields, identify and report fraud and other abusive behaviors; journalists and academics use WHOIS data to conduct research and expose miscreant behavior; and parents use WHOIS data to better understand who they (or their children) are dealing with online. These and other uses improve the security and stability of the Internet and should be encouraged not burdened by barriers of a closed by default system.”