On Wednesday, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran a story about how its staff discovered and reported a security vulnerability in a Missouri state education website that exposed the Social Security numbers of 100,000 elementary and secondary teachers. In a press conference this morning, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson (R) said fixing the flaw could cost the state $50 million, and vowed his administration would seek to prosecute and investigate the “hackers” and anyone who aided the publication in its “attempt to embarrass the state and sell headlines for their news outlet.”

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson (R), vowing to prosecute the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for reporting a security vulnerability that exposed teacher SSNs.

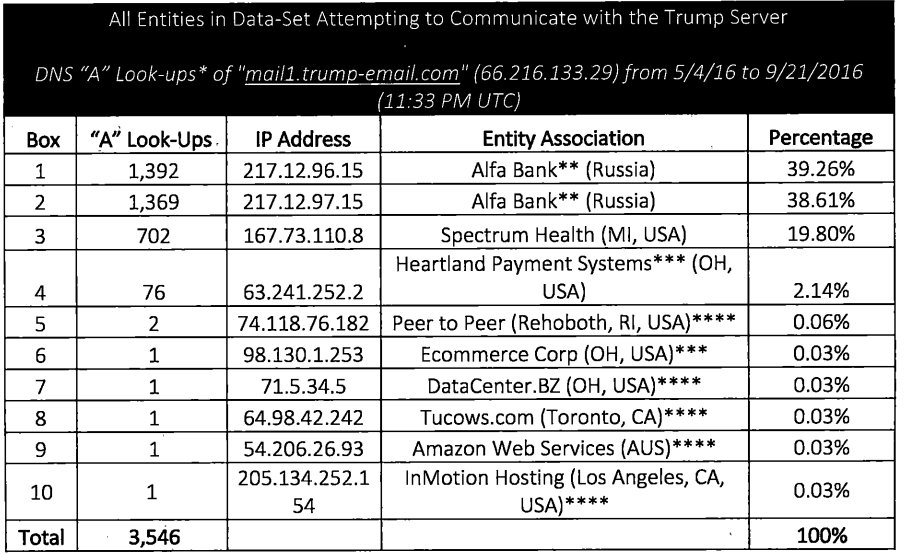

The Post-Dispatch says it discovered the vulnerability in a web application that allowed the public to search teacher certifications and credentials, and that more than 100,000 SSNs were available. The Missouri state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) reportedly removed the affected pages from its website Tuesday after being notified of the problem by the publication (before the story on the flaw was published).

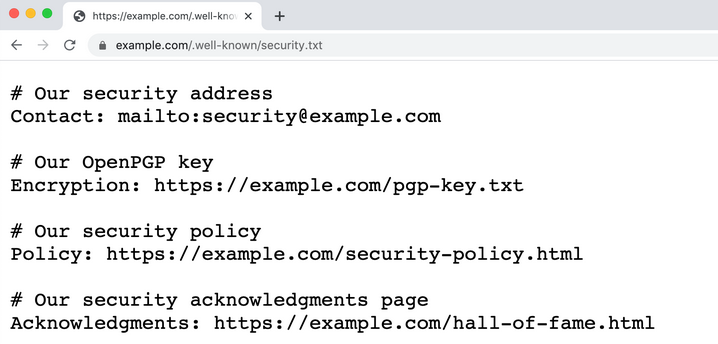

The newspaper said it found that teachers’ Social Security numbers were contained in the HTML source code of the pages involved. In other words, the information was available to anyone with a web browser who happened to also examine the site’s public code using Developer Tools or simply right-clicking on the page and viewing the source code.

The Post-Dispatch reported that it wasn’t immediately clear how long the Social Security numbers and other sensitive information had been vulnerable on the DESE website, nor was it known if anyone had exploited the flaw.

But in a press conference Thursday morning, Gov. Parson said he would seek to prosecute and investigate the reporter and the region’s largest newspaper for “unlawfully” accessing teacher data.

“This administration is standing up against any and all perpetrators who attempt to steal personal information and harm Missourians,” Parson said. “It is unlawful to access encoded data and systems in order to examine other peoples’ personal information. We are coordinating state resources to respond and utilize all legal methods available. My administration has notified the Cole County prosecutor of this matter, the Missouri State Highway Patrol’s Digital Forensics Unit will also be conducting an investigation of all of those involved. This incident alone may cost Missouri taxpayers as much as $50 million.”

While threatening to prosecute the reporters to the fullest extent of the law, Parson sought to downplay the severity of the security weakness, saying the reporter only unmasked three Social Security numbers, and that “there was no option to decode Social Security numbers for all educators in the system all at once.”

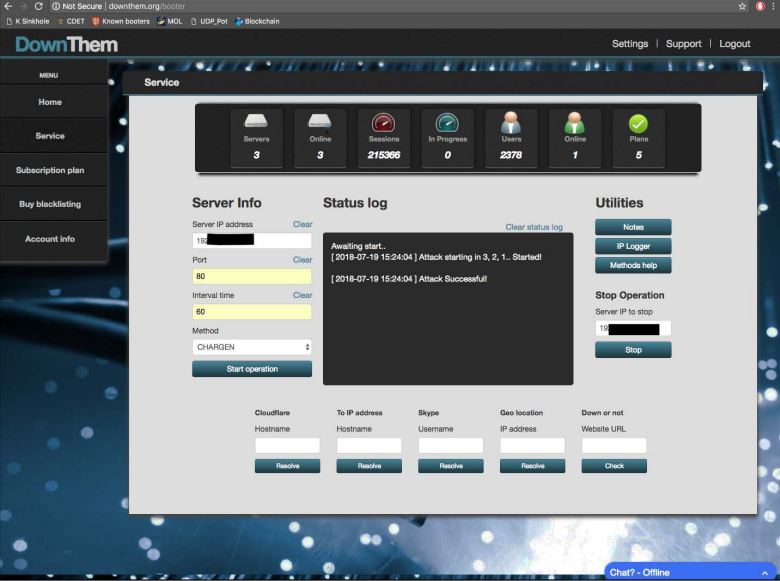

“The state is committed to bringing to justice anyone who hacked our systems or anyone who aided them to do so,” Parson continued. “A hacker is someone who gains unauthorized access to information or content. This individual did not have permission to do what they did. They had no authorization to convert or decode, so this was clearly a hack.” Continue reading