Identity thieves who specialize in running up unauthorized lines of credit in the names of small businesses are having a field day with all of the closures and economic uncertainty wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, KrebsOnSecurity has learned. This story is about the victims of a particularly aggressive business ID theft ring that’s spent years targeting small businesses across the country and is now pivoting toward using that access for pandemic assistance loans and unemployment benefits.

Most consumers are likely aware of the threat from identity theft, which occurs when crooks apply for new lines of credit in your name. But the same crime can be far more costly and damaging when thieves target small businesses. Unfortunately, far too many entrepreneurs are simply unaware of the threat or don’t know how to be watchful for it.

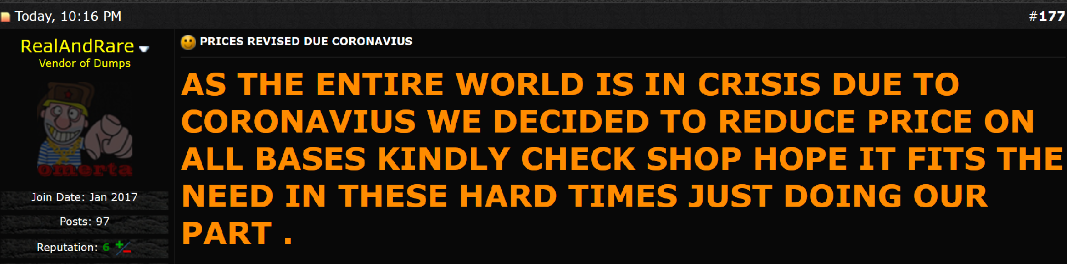

What’s more, with so many small enterprises going out of business or sitting dormant during the COVID-19 pandemic, organized fraud rings have an unusually rich pool of targets to choose from.

Short Hills, N.J.-based Dun & Bradstreet [NYSE:DNB] is a data analytics company that acts as a kind of de facto credit bureau for companies: When a business owner wants to open a new line of credit, creditors typically check with Dun & Bradstreet to gauge the business’s history and trustworthiness.

In 2019, Dun & Bradstreet saw more than a 100 percent increase in business identity theft. For 2020, the company estimates an overall 258 percent spike in the crime. Dun & Bradstreet said that so far this year it has received over 4,700 tips and leads where business identity theft or malfeasance are suspected.

“The ferocity of cyber criminals to take advantage of COVID-19 uncertainties by preying on small businesses is disturbing,” said Andrew LaMarca, who leads the global high-risk and fraud team at Dun & Bradstreet.

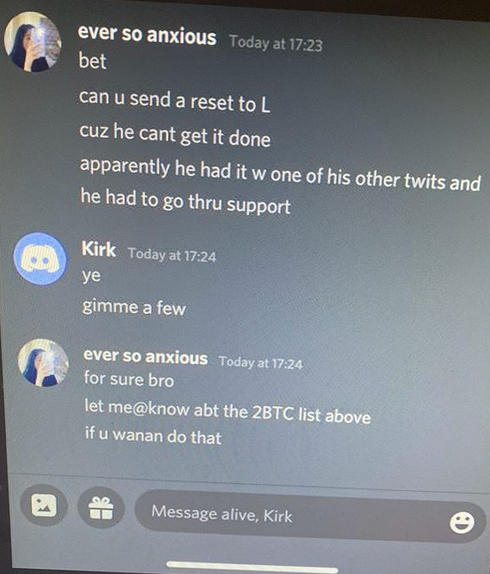

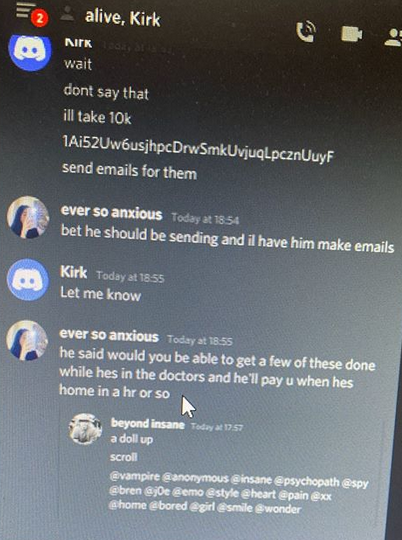

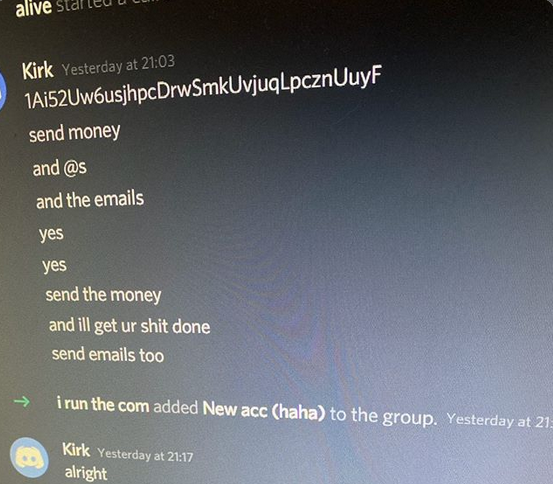

For the past several months, Milwaukee, Wisc. based cyber intelligence firm Hold Security has been monitoring the communications between and among a businesses ID theft gang apparently operating in Georgia and Florida but targeting businesses throughout the United States. That surveillance has helped to paint a detailed picture of how business ID thieves operate, as well as the tricks they use to gain credit in a company’s name.

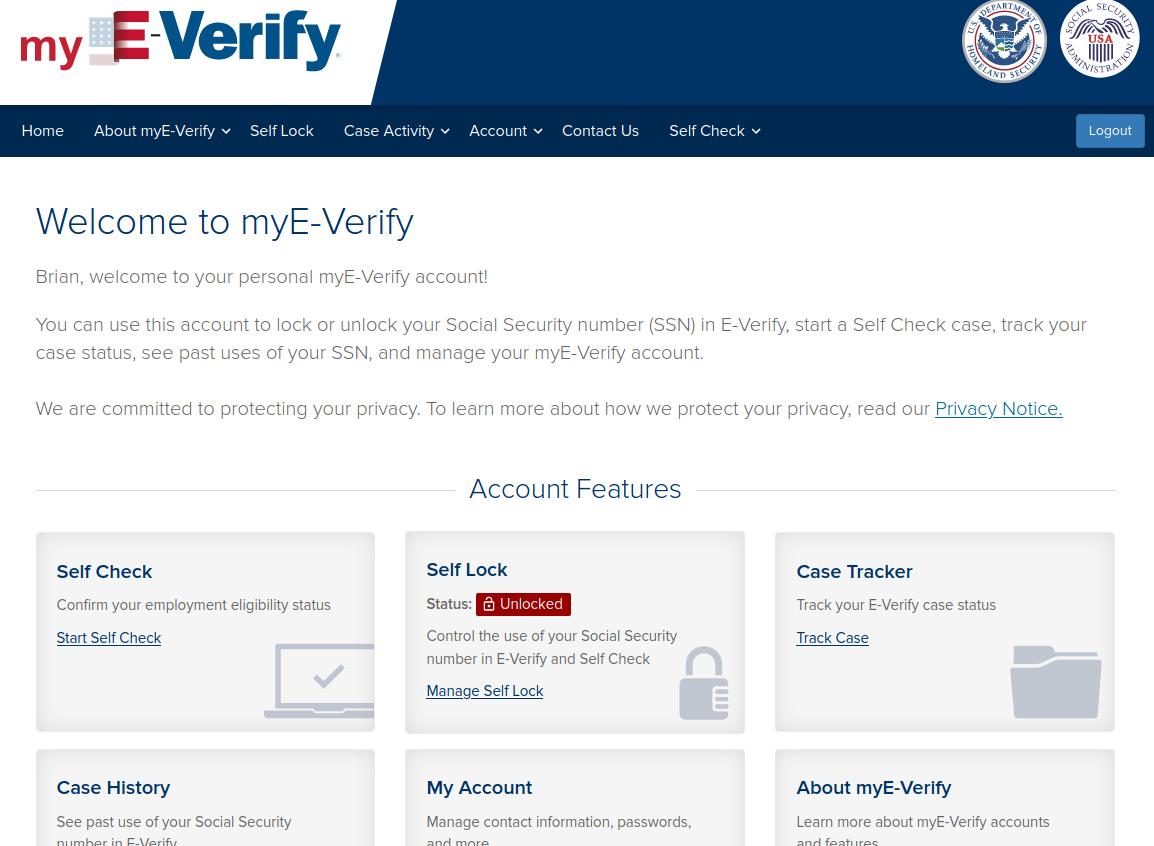

Hold Security founder Alex Holden said the group appears to target both active and dormant or inactive small businesses. The gang typically will start by looking up the business ownership records at the Secretary of State website that corresponds to the company’s state of incorporation. From there, they identify the officers and owners of the company, acquire their Social Security and Tax ID numbers from the dark web and other sources online.

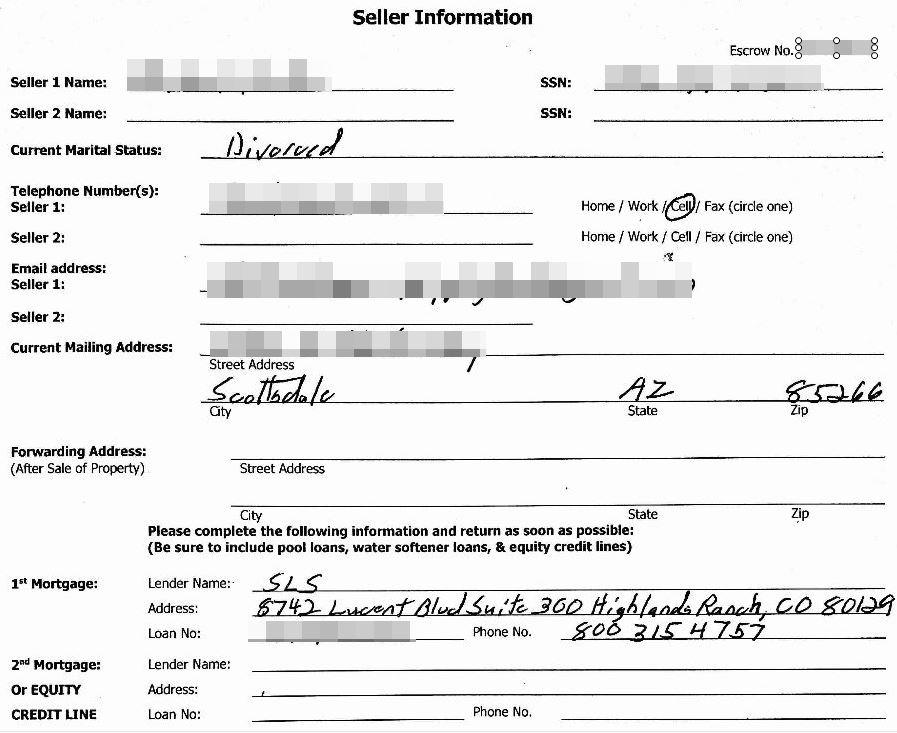

To prove ownership over the hijacked firms, they hire low-wage image editors online to help fabricate and/or modify a number of official documents tied to the business — including tax records and utility bills.

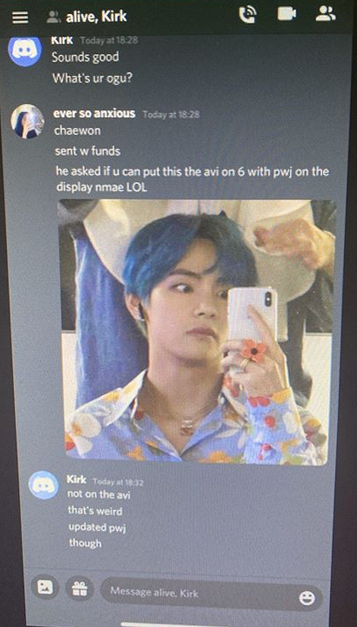

The scammers frequently then file phony documents with the Secretary of State’s office in the name(s) of the business owners, but include a mailing address that they control. They also create email addresses and domain names that mimic the names of the owners and the company to make future credit applications appear more legitimate, and submit the listings to business search websites, such as yellowpages.com.

For both dormant and existing businesses, the fraudsters attempt to create or modify the target company’s accounts at Dun & Bradstreet. In some cases, the scammers create dashboard accounts in the business’s names at Dun & Bradstreet’s credit builder portal; in others, the bad guys have actually hacked existing business accounts at DNB, requesting a new DUNS numbers for the business (a DUNS number is a unique, nine-digit identifier for businesses).

Finally, after the bogus profiles are approved by Dun & Bradstreet, the gang waits a few weeks or months and then starts applying for new lines of credit in the target business’s name at stores like Home Depot, Office Depot and Staples. Then they go on a buying spree with the cards issued by those stores.

Usually, the first indication a victim has that they’ve been targeted is when the debt collection companies start calling.

“They are using mostly small companies that are still active businesses but currently not operating because of COVID-19,” Holden said. “With this gang, we see four or five people working together. The team leader manages the work between people. One person seems to be in charge of getting stolen cards from the dark web to pay for the reactivation of businesses through the secretary of state sites. Another team member works on revising the business documents and registering them on various sites. The others are busy looking for specific businesses they want to revive.”

Holden said the gang appears to find success in getting new lines of credit with about 20 percent of the businesses they target.

“One’s personal credit is nothing compared to the ability of corporations to borrow money,” he said. “That’s bad because while the credit system may be flawed for individuals, it’s an even worse situation on average when we’re talking about businesses.”

Holden said over the past few months his firm has seen communications between the gang’s members indicating they have temporarily shifted more of their energy and resources to defrauding states and the federal government by filing unemployment insurance claims and apply for pandemic assistance loans with the Small Business Administration.

“It makes sense, because they’ve already got control over all these dormant businesses,” he said. “So they’re now busy trying to get unemployment payments and SBA loans in the names of these companies and their employees.”

PHANTOM OFFICES

Hold Security shared data intercepted from the gang that listed the personal and financial details of dozens of companies targeted for ID theft, including Dun & Bradstreet logins the crooks had created for the hijacked businesses. Dun & Bradstreet declined to comment on the matter, other than to say it was working with federal and state authorities to alert affected businesses and state regulators.

Among those targeted was Environmental Safety Consultants Inc. (ESC), a 37-year-old environmental engineering firm based in Bradenton, Fla. ESC owner Scott Russell estimates his company was initially targeted nearly two years ago, and that he first became aware something wasn’t right when he recently began getting calls from Home Depot’s corporate offices inquiring about the company’s delinquent account.

But Russell said he didn’t quite grasp the enormity of the situation until last year, when he was contacted by the manager of a virtual office space across town who told him about a suspiciously large number of deliveries at an office space that was rented out in his name.

Russell had never rented that particular office. Rather, the thieves had done it for him, using his name and the name of his business. The office manager said the deliveries came virtually non-stop, even though there was apparently no business operating within the rented premises. And in each case, shortly after the shipments arrived someone would show up and cart them away.

“She said we don’t think it’s you,” he recalled. “Turns out, they had paid for a lease in my name with someone else’s credit card. She shared with me a copy of the lease, which included a fraudulent ID and even a vehicle insurance card for a Land Cruiser we got rid of like 15 years ago. The application listed our home address with me and some woman who was not my wife’s name.”

The crates and boxes being delivered to his erstwhile office space were mostly computers and other high-priced items ordered from 10 different Office Depot credit cards that also were not in his name.

“The total value of the electronic equipment that was bought and delivered there was something like $75,000,” Russell said, noting that it took countless hours and phone calls with Office Depot to make it clear they would no longer accept shipments addressed to him or his company. “It was quite spine-tingling to see someone penned a lease in the name of my business and personal identity.”

Even though the virtual office manager had the presence of mind to take photocopies of the driver’s licenses presented by the people arriving to pick up the fraudulent shipments, the local police seemed largely uninterested in pursuing the case, Russell said.

“I went to the local county sheriff’s office and showed them all the documentation I had and the guy just yawned and said he’d get right on it,” he recalled. “The place where the office space was rented was in another county, and the detective I spoke to there about it was interested, but he could never get anyone from my county to follow up.” Continue reading

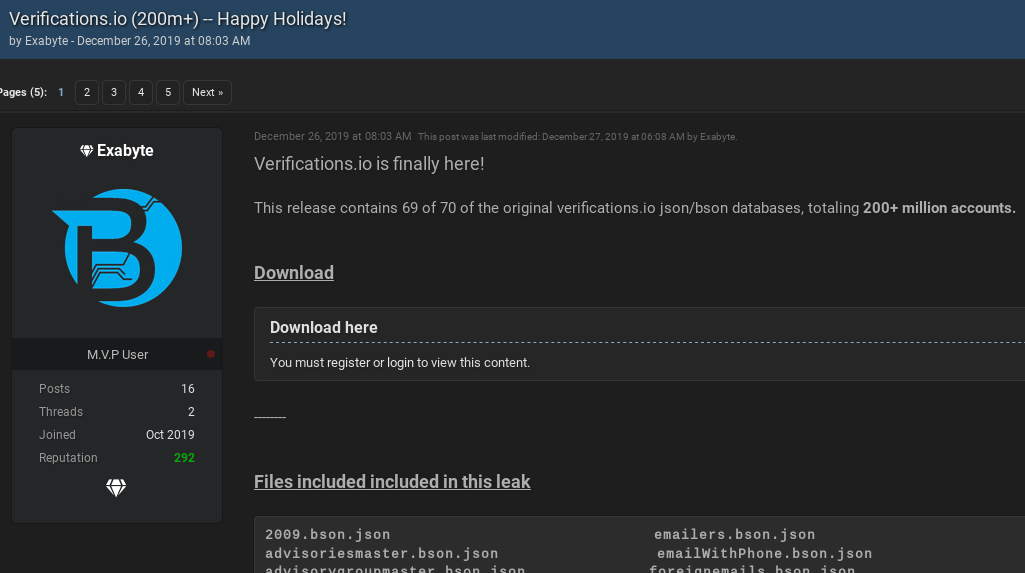

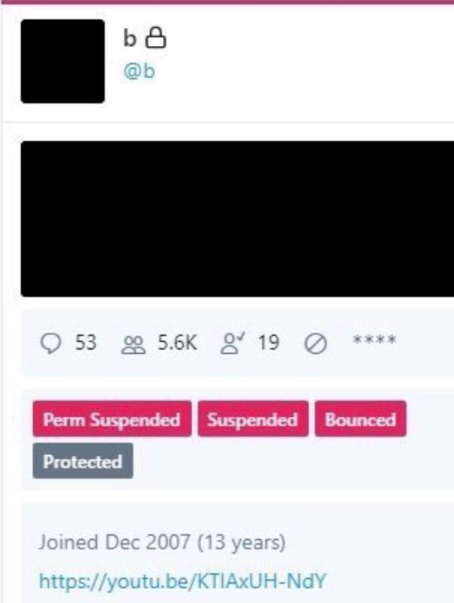

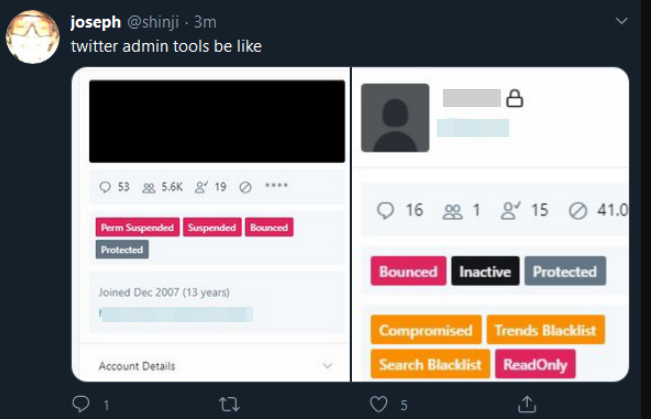

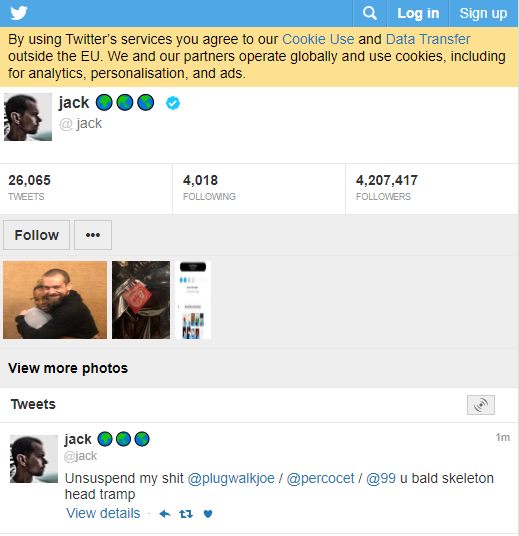

Top of the heap this month in terms of outright scariness is

Top of the heap this month in terms of outright scariness is