The crooks responsible for launching phishing campaigns that netted dozens of employees and more than 100 computer systems last month at Wipro, India’s third-largest IT outsourcing firm, also appear to have targeted a number of other competing providers, including Infosys and Cognizant, new evidence suggests. The clues so far suggest the work of a fairly experienced crime group that is focused on perpetrating gift card fraud.

On Monday, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that multiple sources were reporting a cybersecurity breach at Wipro, a major trusted vendor of IT outsourcing for U.S. companies. The story cited reports from multiple anonymous sources who said Wipro’s trusted networks and systems were being used to launch cyberattacks against the company’s customers.

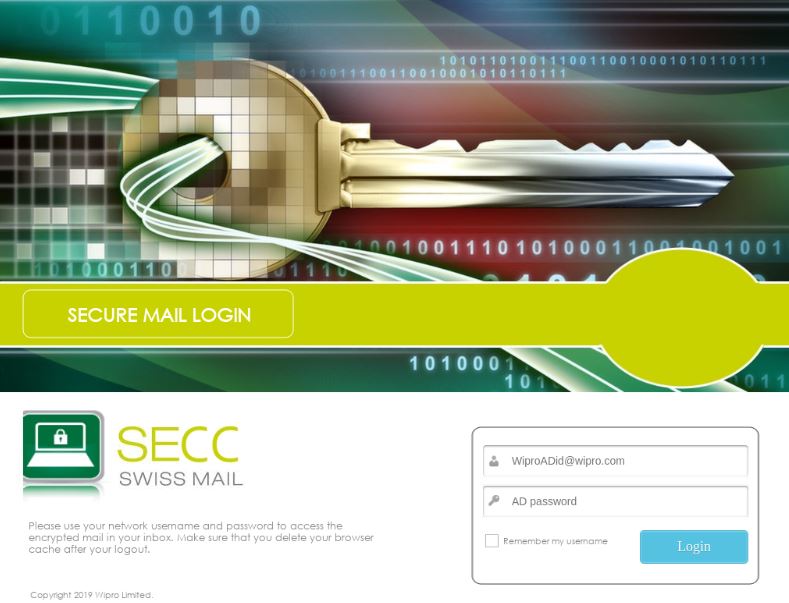

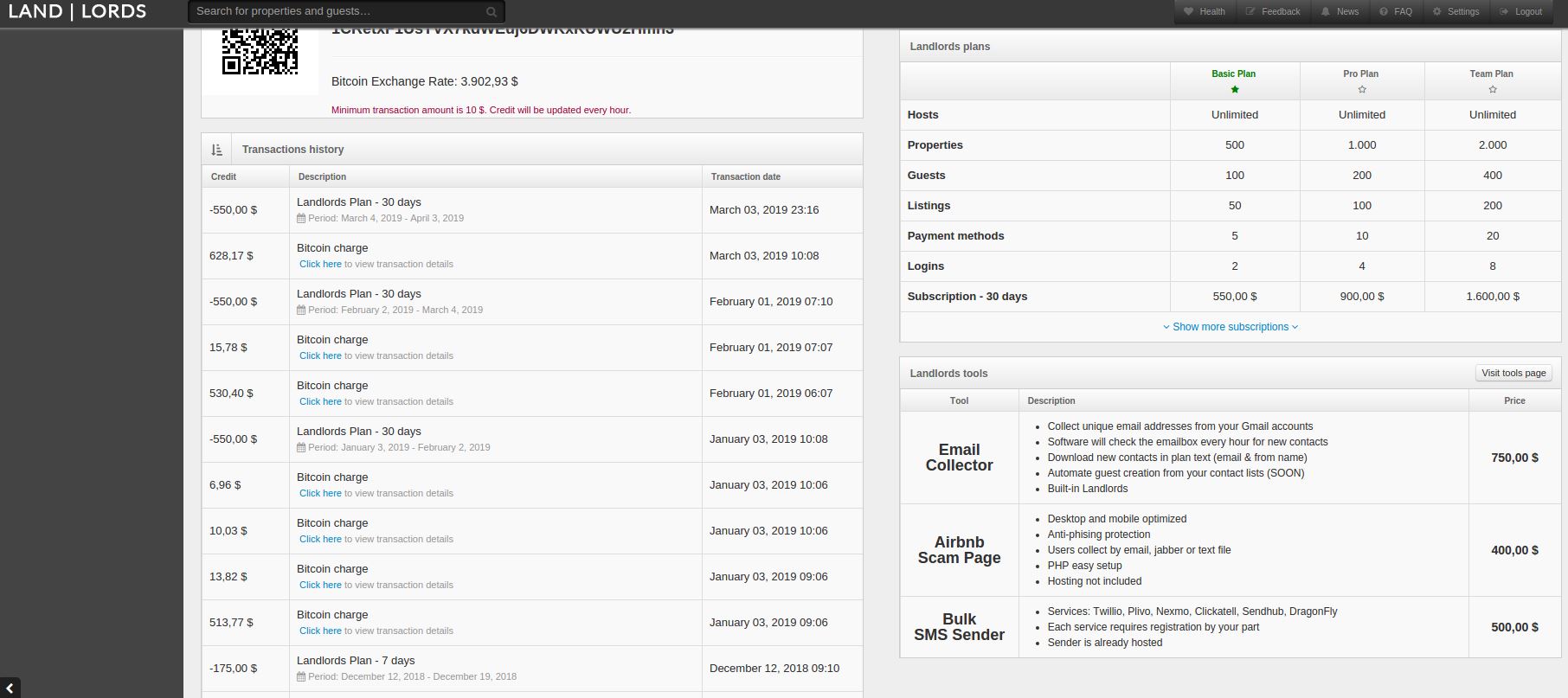

A screen shot of the Wipro phishing site securemail.wipro.com.internal-message[.]app. Image: urlscan.io

If one examines the subdomains tied to just one of the malicious domains mentioned in the IoCs list (internal-message[.]app), one very interesting Internet address is connected to all of them — 185.159.83[.]24. This address is owned by King Servers, a well-known bulletproof hosting company based in Russia.

According to records maintained by Farsight Security, that address is home to a number of other likely phishing domains:

securemail.pcm.com.internal-message[.]app

secure.wipro.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.wipro.com.internal-message[.]app

secure.elavon.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.slalom.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.avanade.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.infosys.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.searshc.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.capgemini.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.cognizant.com.internal-message[.]app

secure.rackspace.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.virginpulse.com.internal-message[.]app

secure.expediagroup.com.internal-message[.]app

securemail.greendotcorp.com.internal-message[.]app

secure.bridge2solutions.com.internal-message[.]app

ns1.internal-message[.]app

ns2.internal-message[.]app

mail.internal-message[.]app

ns3.microsoftonline-secure-login[.]com

ns4.microsoftonline-secure-login[.]com

tashabsolutions[.]xyz

www.tashabsolutions[.]xyz

The subdomains listed above suggest the attackers may also have targeted American retailer Sears; Green Dot, the world’s largest prepaid card vendor; payment processing firm Elavon; hosting firm Rackspace; business consulting firm Avanade; IT provider PCM; and French consulting firm Capgemini, among others. KrebsOnSecurity has reached out to all of these companies for comment, and will update this story in the event any of them respond with relevant information.

WHAT ARE THEY AFTER?

It appears the attackers in this case are targeting companies that in one form or another have access to either a ton of third-party company resources, and/or companies that can be abused to conduct gift card fraud.

Wednesday’s follow-up on the Wipro breach quoted an anonymous source close to the investigation saying the criminals responsible for breaching Wipro appear to be after anything they can turn into cash fairly quickly. That source, who works for a large U.S. retailer, said the crooks who broke into Wipro used their access to perpetrate gift card fraud at the retailer’s stores.

Another source said the investigation into the Wipro breach by a third party company has determined so far the intruders compromised more than 100 Wipro systems and installed on each of them ScreenConnect, a legitimate remote access tool. Investigators believe the intruders were using the ScreenConnect software on the hacked Wipro systems to connect remotely to Wipro client systems, which were then used to leverage further access into Wipro customer networks.

This is remarkably similar to activity that was directed against a U.S. based company in 2016 and 2017. In May 2018, Maritz Holdings Inc., a Missouri-based firm that handles customer loyalty and gift card programs for third-parties, sued Cognizant (PDF), saying a forensic investigation determined that hackers used Cognizant’s resources in an attack on Maritz’s loyalty program that netted the attackers more than $11 million in fraudulent eGift cards. Continue reading

And yet, here I am again writing the second story this week about a possibly serious security breach at an Indian company that provides IT support and outsourcing for a ridiculous number of major U.S. corporations (spoiler alert: the second half of this story actually contains quite a bit of news about the breach investigation).

And yet, here I am again writing the second story this week about a possibly serious security breach at an Indian company that provides IT support and outsourcing for a ridiculous number of major U.S. corporations (spoiler alert: the second half of this story actually contains quite a bit of news about the breach investigation).

According to security firm

According to security firm  Adobe’s Patch Tuesday includes security updates for its

Adobe’s Patch Tuesday includes security updates for its