One of the cybercrime underground’s more active sellers of Social Security numbers, background and credit reports has been pulling data from hacked accounts at the U.S. consumer data broker USinfoSearch, KrebsOnSecurity has learned.

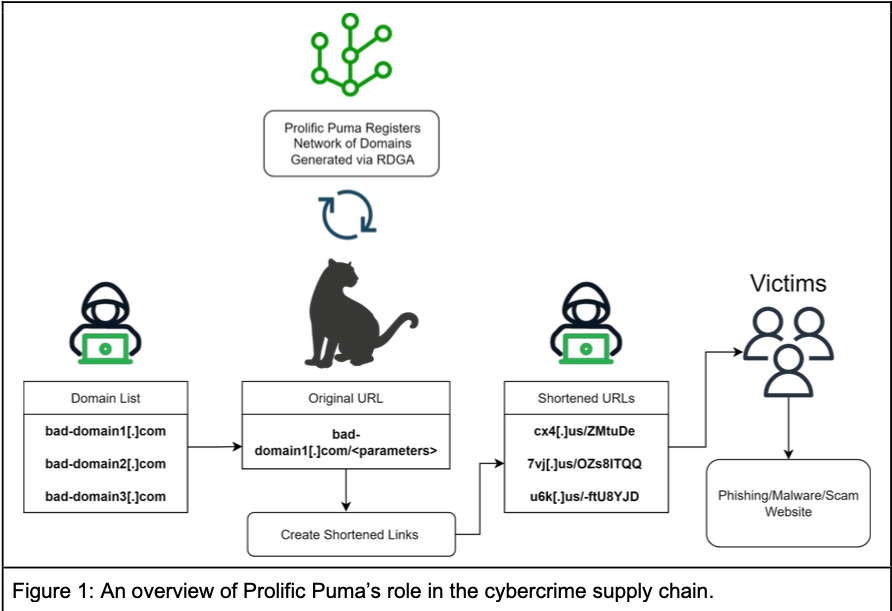

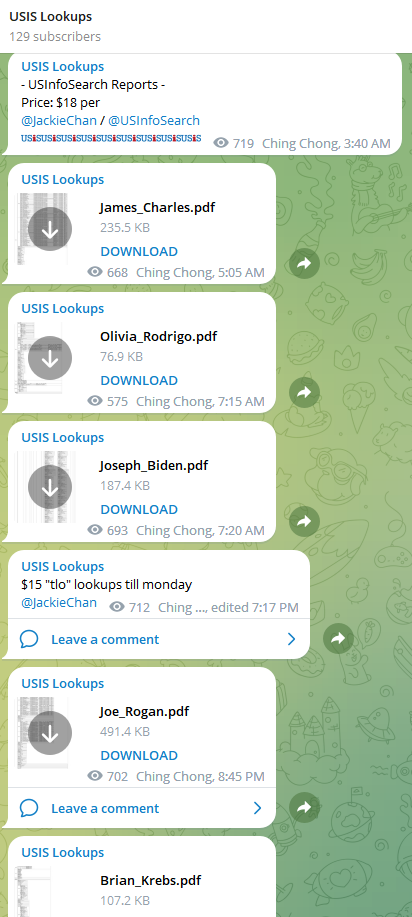

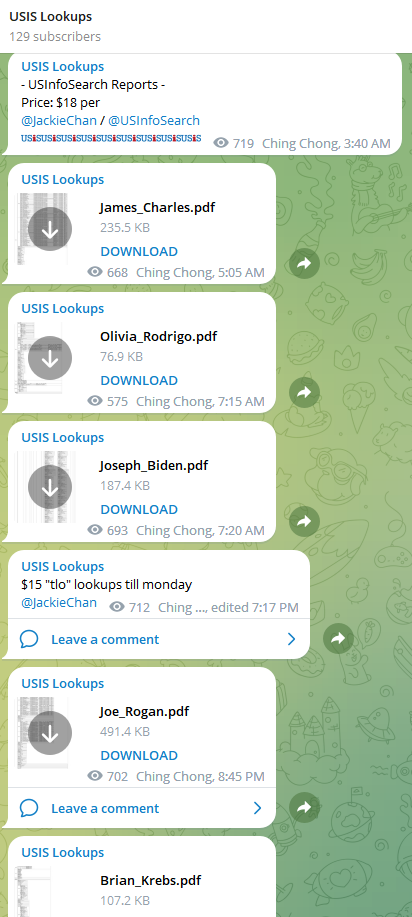

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.

USiSLookups is the project of a cybercriminal who uses the nicknames JackieChan/USInfoSearch, and the Telegram channel for this service features a small number of sample background reports, including that of President Joe Biden, and podcaster Joe Rogan. The data in those reports includes the subject’s date of birth, address, previous addresses, previous phone numbers and employers, known relatives and associates, and driver’s license information.

JackieChan’s service abuses the name and trademarks of Columbus, OH based data broker USinfoSearch, whose website says it provides “identity and background information to assist with risk management, fraud prevention, identity and age verification, skip tracing, and more.”

“We specialize in non-FCRA data from numerous proprietary sources to deliver the information you need, when you need it,” the company’s website explains. “Our services include API-based access for those integrating data into their product or application, as well as bulk and batch processing of records to suit every client.”

As luck would have it, my report was also listed in the Telegram channel for this identity fraud service, presumably as a teaser for would-be customers. On October 19, 2023, KrebsOnSecurity shared a copy of this file with the real USinfoSearch, along with a request for information about the provenance of the data.

USinfoSearch said it would investigate the report, which appears to have been obtained on or before June 30, 2023. On Nov. 9, 2023, Scott Hostettler, general manager of USinfoSearch parent Martin Data LLC shared a written statement about their investigation that suggested the ID theft service was trying to pass off someone else’s consumer data as coming from USinfoSearch:

Regarding the Telegram incident, we understand the importance of protecting sensitive information and upholding the trust of our users is our top priority. Any allegation that we have provided data to criminals is in direct opposition to our fundamental principles and the protective measures we have established and continually monitor to prevent any unauthorized disclosure. Because Martin Data has a reputation for high-quality data, thieves may steal data from other sources and then disguise it as ours. While we implement appropriate safeguards to guarantee that our data is only accessible by those who are legally permitted, unauthorized parties will continue to try to access our data. Thankfully, the requirements needed to pass our credentialing process is tough even for established honest companies.

USinfoSearch’s statement did not address any questions put to the company, such as whether it requires multi-factor authentication for customer accounts, or whether my report had actually come from USinfoSearch’s systems.

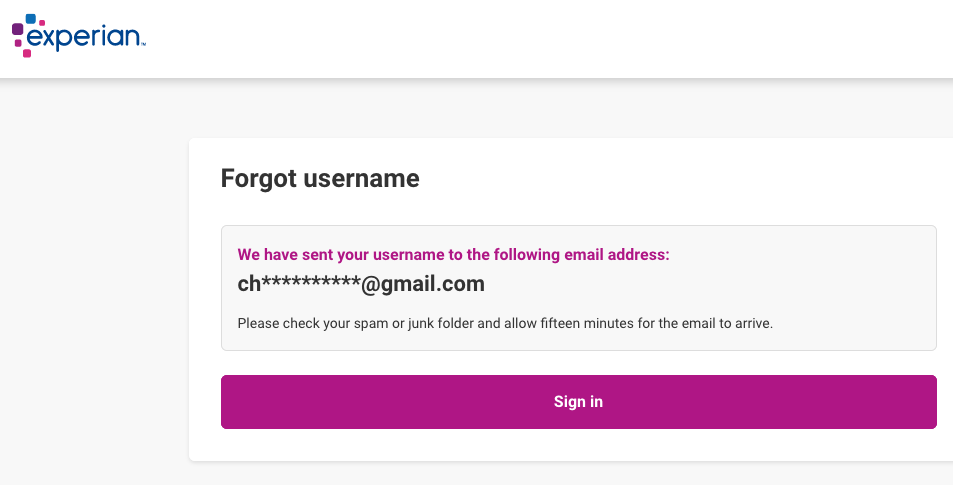

After much badgering, on Nov. 21 Hostettler acknowledged that the USinfoSearch identity fraud service on Telegram was in fact pulling data from an account belonging to a vetted USinfoSearch client.

“I do know 100% that my company did not give access to the group who created the bots, but they did gain access to a client,” Hostettler said of the Telegram-based identity fraud service. “I apologize for any inconvenience this has caused.”

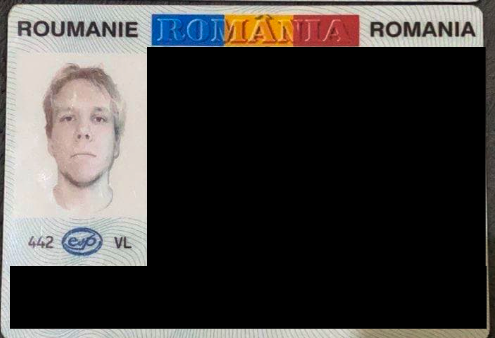

Hostettler said USinfoSearch heavily vets any new potential clients, and that all users are required to undergo a background check and provide certain documents. Even so, he said, several fraudsters each month present themselves as credible business owners or C-level executives during the credentialing process, completing the application and providing the necessary documentation to open a new account.

“The level of skill and craftsmanship demonstrated in the creation of these supporting documents is incredible,” Hostettler said. “The numerous licenses provided appear to be exact replicas of the original document. Fortunately, I’ve discovered several methods of verification that do not rely solely on those documents to catch the fraudsters.”

“These people are unrelenting, and they act without regard for the consequences,” Hostettler continued. “After I deny their access, they will contact us again within the week using the same credentials. In the past, I’ve notified both the individual whose identity is being used fraudulently and the local police. Both are hesitant to act because nothing can be done to the offender if they are not apprehended. That is where most attention is needed.” Continue reading →

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.