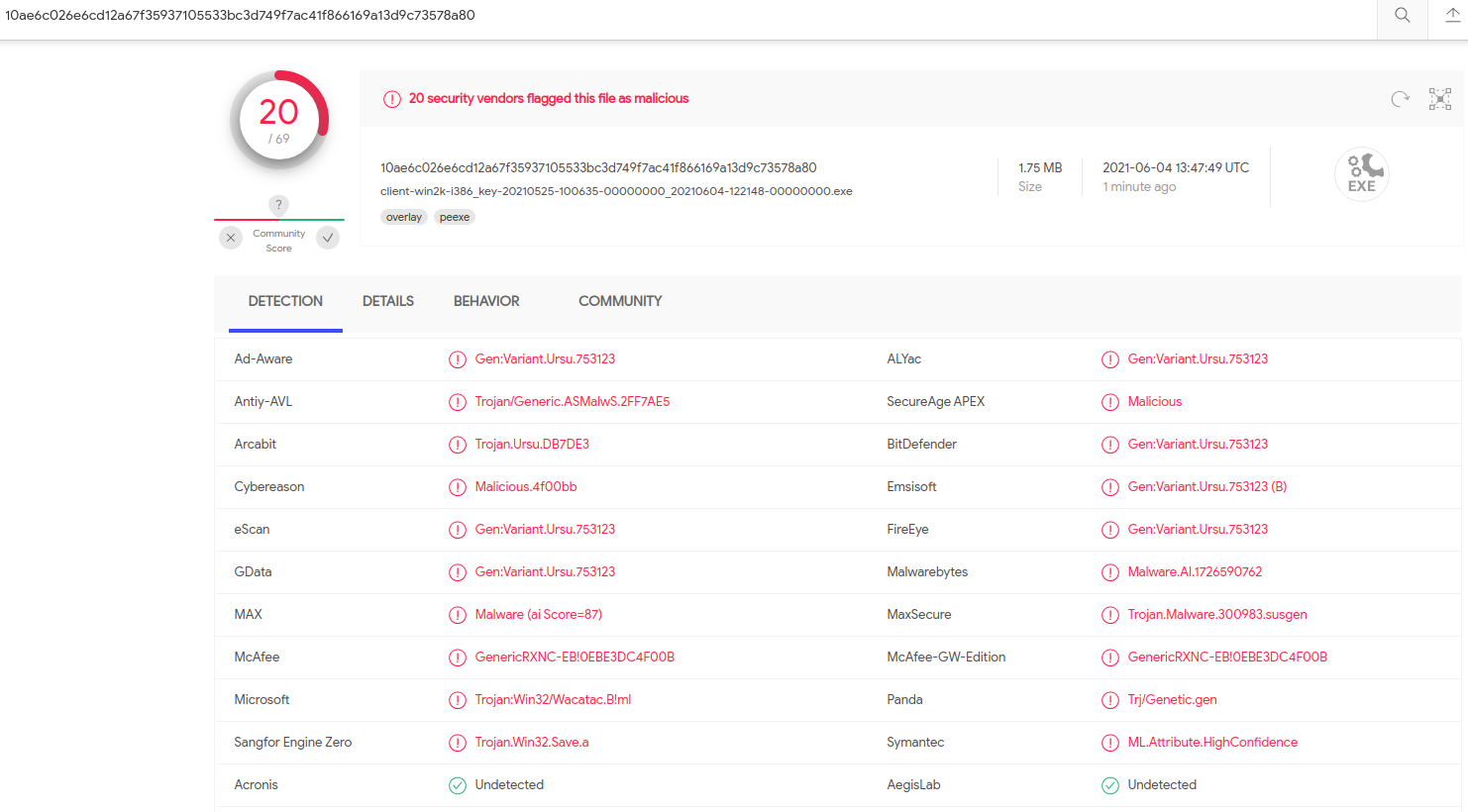

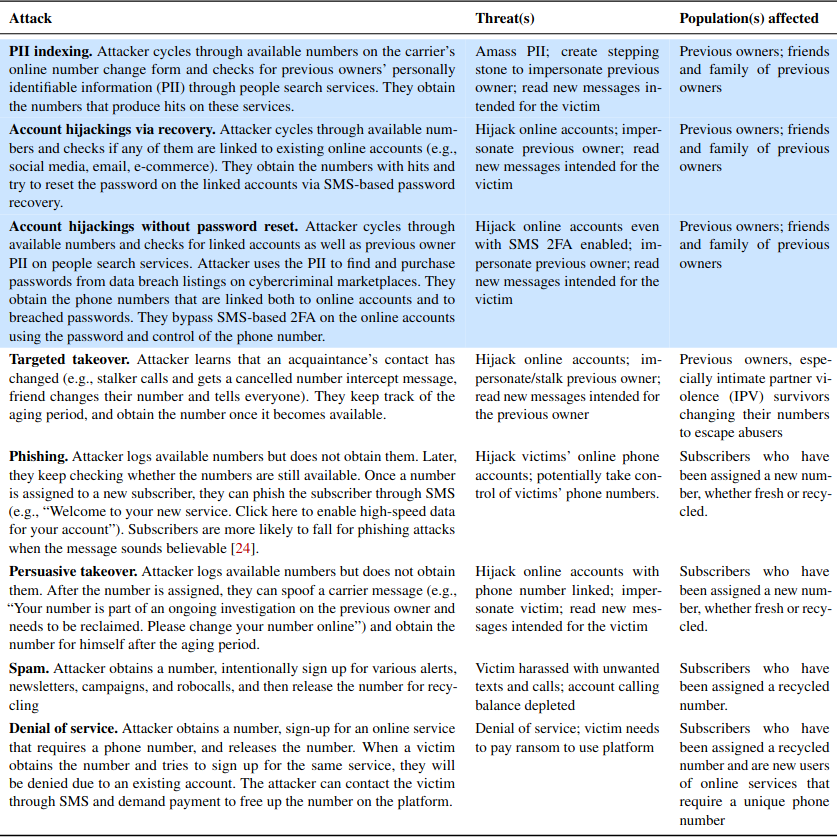

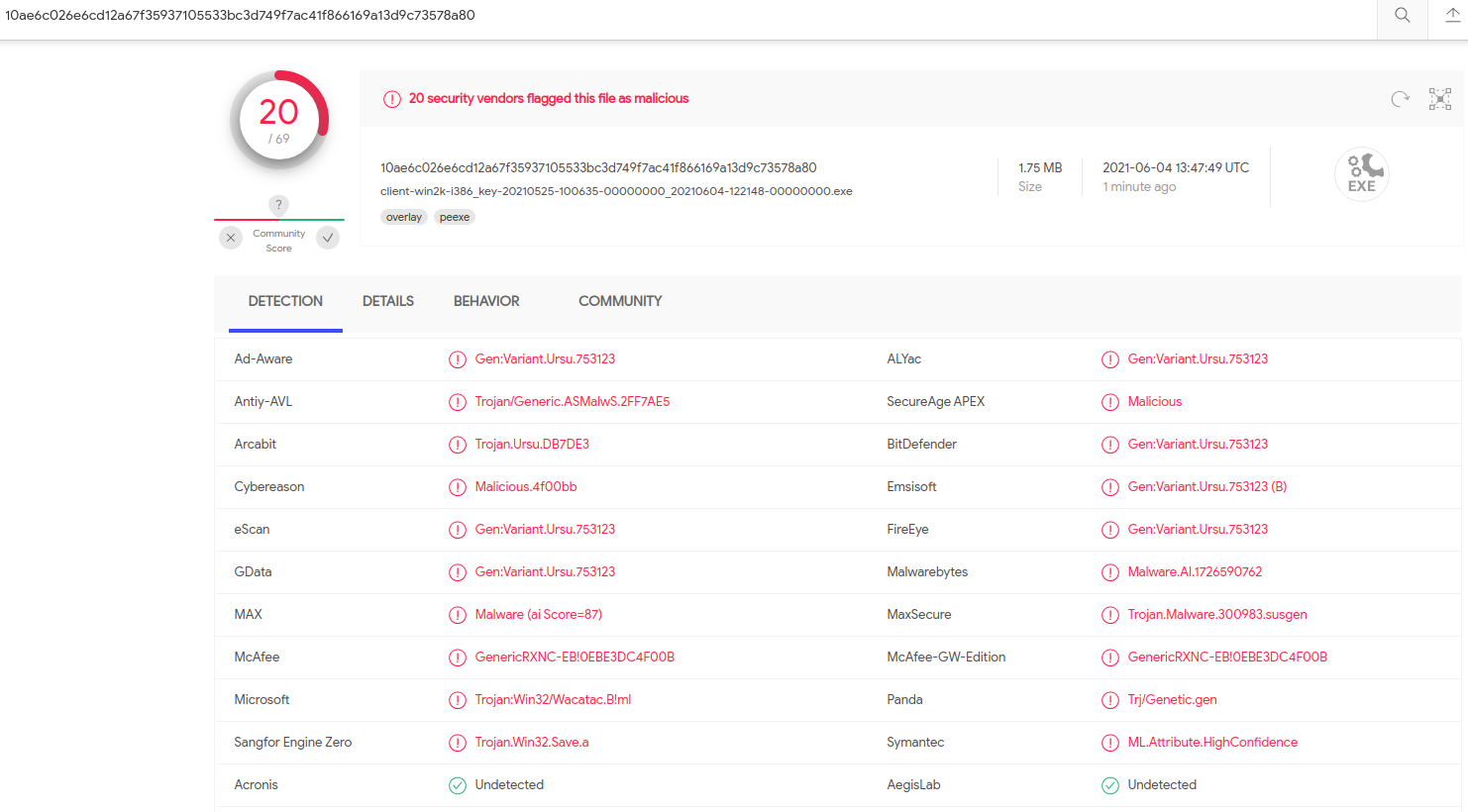

KrebsOnSecurity recently had occasion to contact the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the Russian equivalent of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In the process of doing so, I encountered a small snag: The FSB’s website said in order to communicate with them securely, I needed to download and install an encryption and virtual private networking (VPN) appliance that is flagged by at least 20 antivirus products as malware.

The FSB headquarters at Lubyanka Square, Moscow. Image: Wikipedia.

The reason I contacted the FSB — one of the successor agencies to the Russian KGB — ironically enough had to do with security concerns raised by an infamous Russian hacker about the FSB’s own preferred method of being contacted.

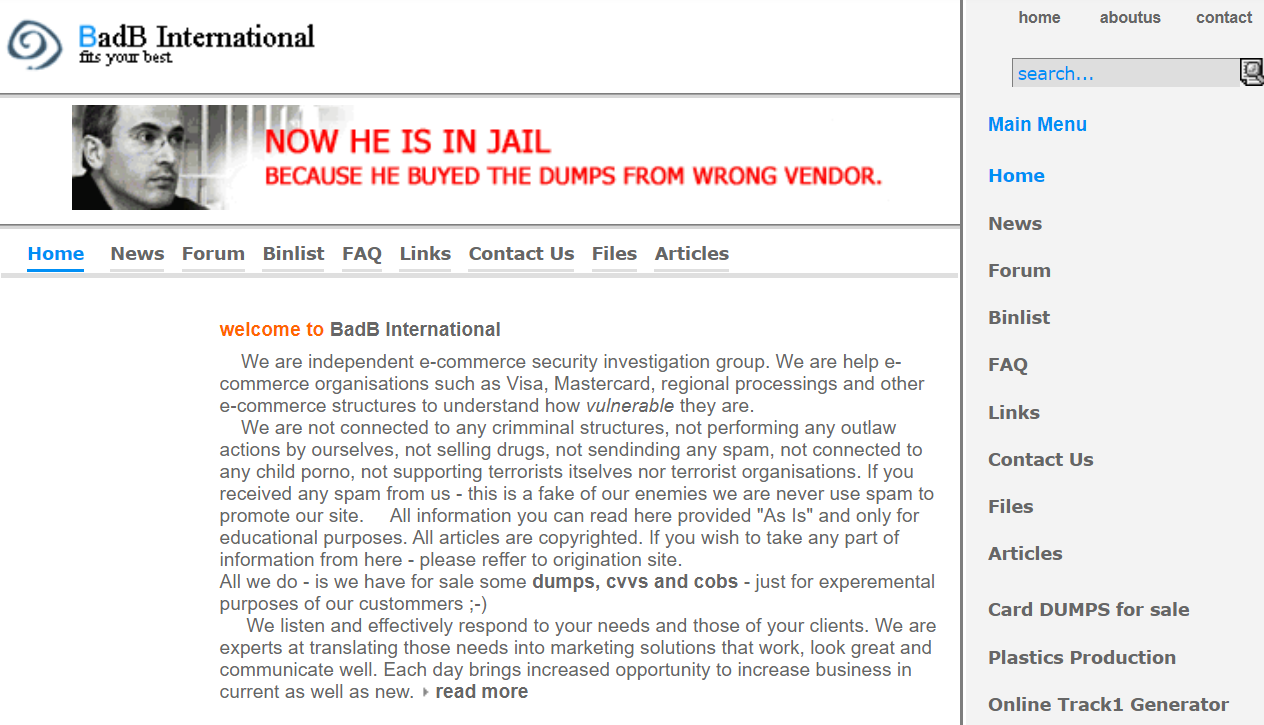

KrebsOnSecurity was seeking comment from the FSB about a blog post published by Vladislav “BadB” Horohorin, a former international stolen credit card trafficker who served seven years in U.S. federal prison for his role in the theft of $9 million from RBS WorldPay in 2009. Horohorin, a citizen of Russia, Israel and Ukraine, is now back where he grew up in Ukraine, running a cybersecurity consulting business.

Horohorin’s BadB carding store, badb[.]biz, circa 2007. Image: Archive.org.

Visit the FSB’s website and you might notice its web address starts with http:// instead of https://, meaning the site is not using an encryption certificate. In practical terms, any information shared between the visitor and the website is sent in plain text and will be visible to anyone who has access to that traffic.

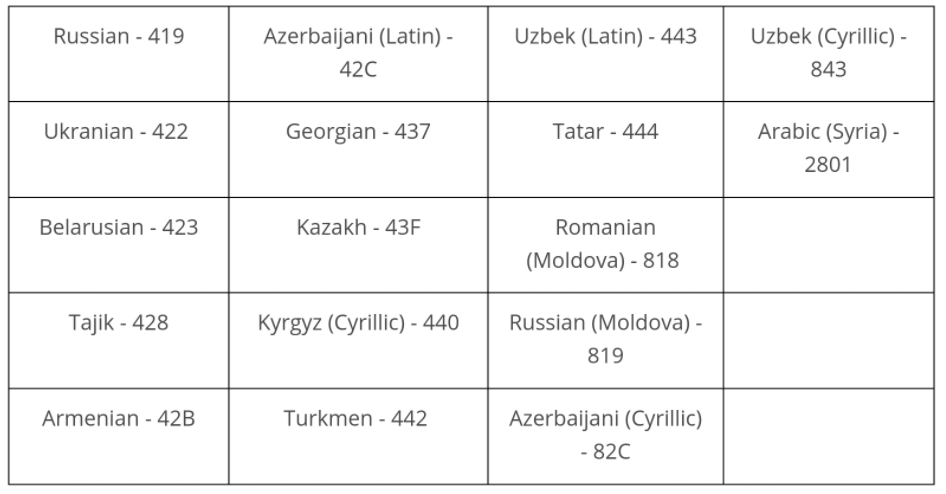

This appears to be the case regardless of which Russian government site you visit. According to Russian search giant Yandex, the laws of the Russian Federation demand that encrypted connections be installed according to the Russian GOST cryptographic algorithm.

That means those who have a reason to send encrypted communications to a Russian government organization — including ordinary things like making a payment for a government license or fine, or filing legal documents — need to first install CryptoPro, a Windows-only application that loads the GOST encryption libraries on a user’s computer.

But if you want to talk directly to the FSB over an encrypted connection, you can just install their own client, which bundles the CryptoPro code. Visit the FSB’s site and select the option to “transfer meaningful information to operational units,” and you’ll see a prompt to install a “random number generation” application that is needed before a specific contact form on the FSB’s website will load properly.

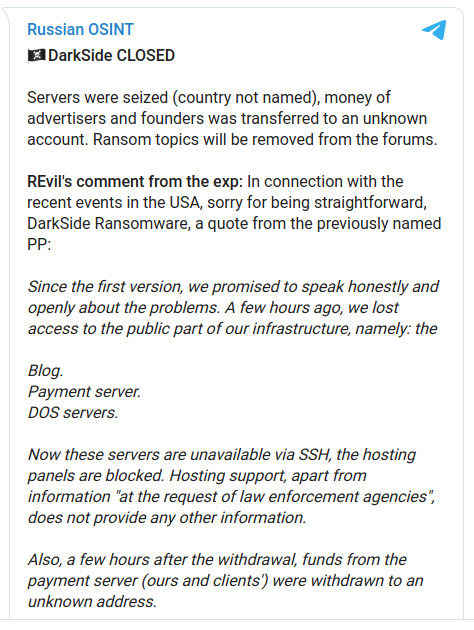

Mind you, I’m not suggesting anyone go do that: Horohorin pointed out that this random number generator was flagged by 20 different antivirus and security products as malicious.

“Think well before contacting the FSB for any questions or dealing with them, and if you nevertheless decide to do this, it is better to use a virtual machine,” Horohorin wrote. “And a spacesuit. And, preferably, while in another country.”

Antivirus product detections on the FSB’s VPN software. Image: VirusTotal.

It’s probably worth mentioning that the FSB is the same agency that’s been sanctioned for malicious cyber activity by the U.S. government on multiple occasions over the past five years. According to the most recent sanctions by the U.S. Treasury Department, the FSB is known for recruiting criminal hackers from underground forums and offering them legal cover for their actions.

“To bolster its malicious cyber operations, the FSB cultivates and co-opts criminal hackers, including the previously designated Evil Corp., enabling them to engage in disruptive ransomware attacks and phishing campaigns,” reads a Treasury assessment from April 2021.

While Horohorin seems convinced the FSB is disseminating malware, it is not unusual for a large number of security tools used by VirusTotal or other similar malware “sandbox” services to incorrectly flag safe files as bad or suspicious — an all-too-common condition known as a “false positive.”

Late last year I warned my followers on Twitter to put off installing updates for their Dell products until the company could explain why a bunch of its software drivers were being detected as malware by two dozen antivirus tools. Those all turned out to be false positives.

To really figure out what this FSB software was doing, I turned to Lance James, the founder of Unit221B, a New York City based cybersecurity firm. James said each download request generates a new executable program. That is because the uniqueness of the file itself is part of what makes the one-to-one encrypted connection possible. Continue reading →