Chip-based credit and debit cards are designed to make it infeasible for skimming devices or malware to clone your card when you pay for something by dipping the chip instead of swiping the stripe. But a recent series of malware attacks on U.S.-based merchants suggest thieves are exploiting weaknesses in how certain financial institutions have implemented the technology to sidestep key chip card security features and effectively create usable, counterfeit cards.

A chip-based credit card. Image: Wikipedia.

Traditional payment cards encode cardholder account data in plain text on a magnetic stripe, which can be read and recorded by skimming devices or malicious software surreptitiously installed in payment terminals. That data can then be encoded onto anything else with a magnetic stripe and used to place fraudulent transactions.

Newer, chip-based cards employ a technology known as EMV that encrypts the account data stored in the chip. The technology causes a unique encryption key — referred to as a token or “cryptogram” — to be generated each time the chip card interacts with a chip-capable payment terminal.

Virtually all chip-based cards still have much of the same data that’s stored in the chip encoded on a magnetic stripe on the back of the card. This is largely for reasons of backward compatibility since many merchants — particularly those in the United States — still have not fully implemented chip card readers. This dual functionality also allows cardholders to swipe the stripe if for some reason the card’s chip or a merchant’s EMV-enabled terminal has malfunctioned.

But there are important differences between the cardholder data stored on EMV chips versus magnetic stripes. One of those is a component in the chip known as an integrated circuit card verification value or “iCVV” for short — also known as a “dynamic CVV.”

The iCVV differs from the card verification value (CVV) stored on the physical magnetic stripe, and protects against the copying of magnetic-stripe data from the chip and the use of that data to create counterfeit magnetic stripe cards. Both the iCVV and CVV values are unrelated to the three-digit security code that is visibly printed on the back of a card, which is used mainly for e-commerce transactions or for card verification over the phone.

The appeal of the EMV approach is that even if a skimmer or malware manages to intercept the transaction information when a chip card is dipped, the data is only valid for that one transaction and should not allow thieves to conduct fraudulent payments with it going forward.

However, for EMV’s security protections to work, the back-end systems deployed by card-issuing financial institutions are supposed to check that when a chip card is dipped into a chip reader, only the iCVV is presented; and conversely, that only the CVV is presented when the card is swiped. If somehow these do not align for a given transaction type, the financial institution is supposed to decline the transaction.

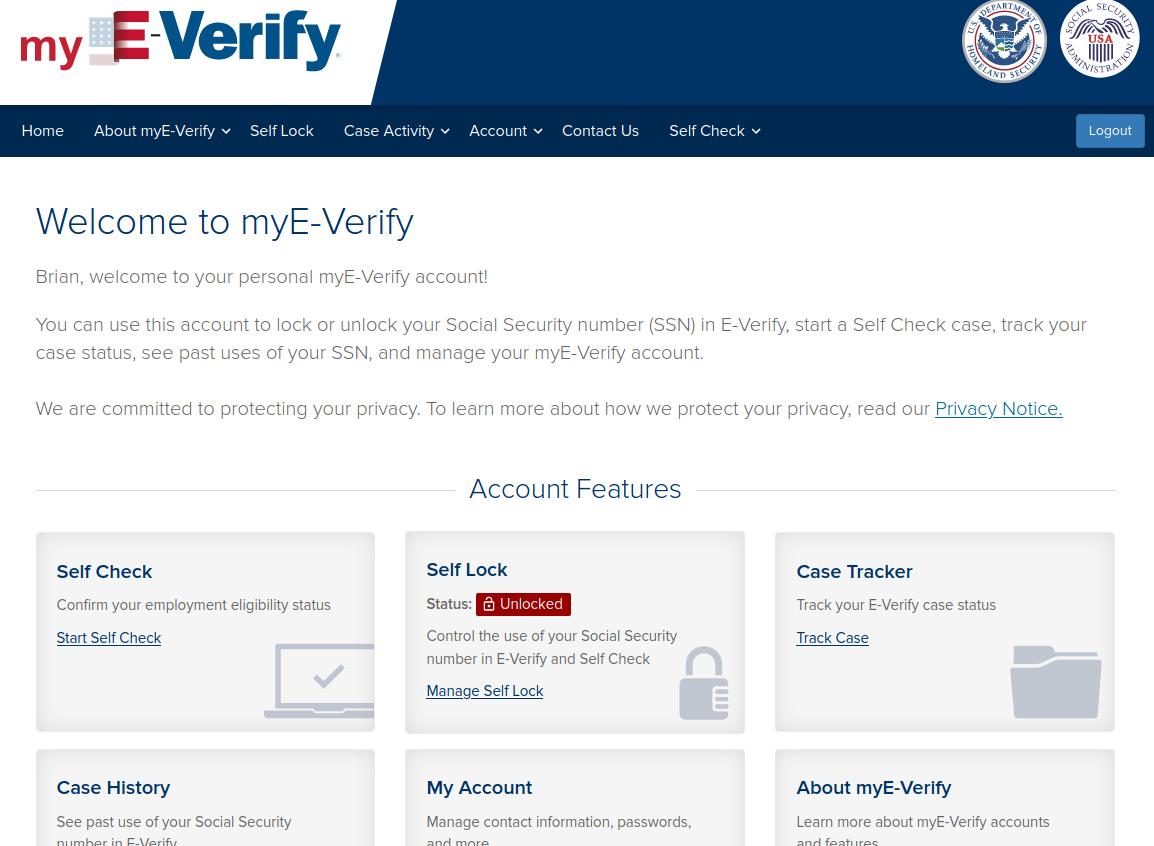

The trouble is that not all financial institutions have properly set up their systems this way. Unsurprisingly, thieves have known about this weakness for years. In 2017, I wrote about the increasing prevalence of “shimmers,” high-tech card skimming devices made to intercept data from chip card transactions.

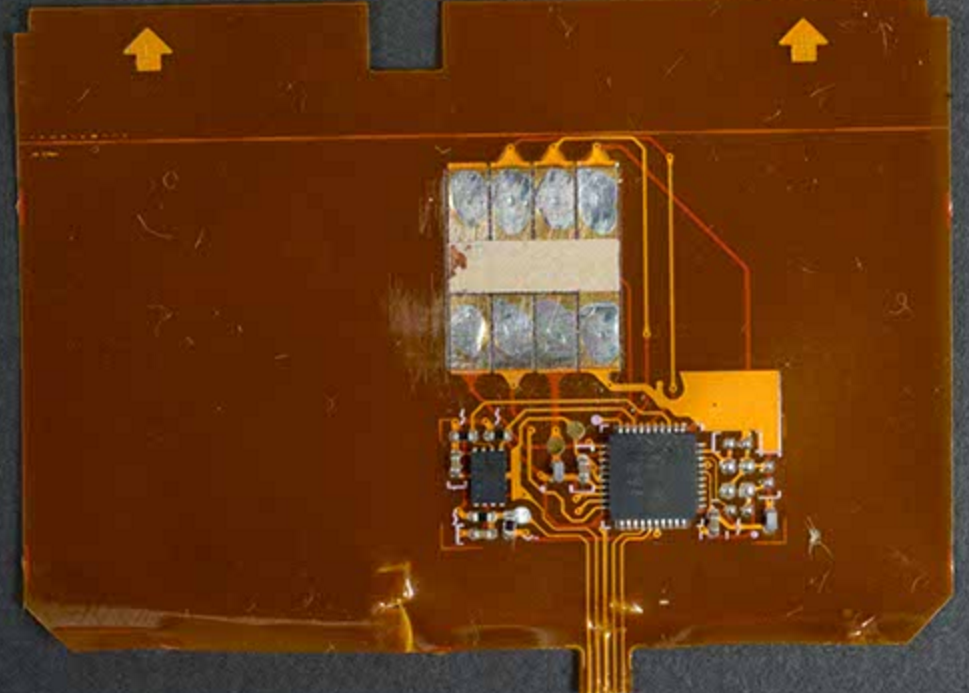

A close-up of a shimmer found on a Canadian ATM. Source: RCMP.

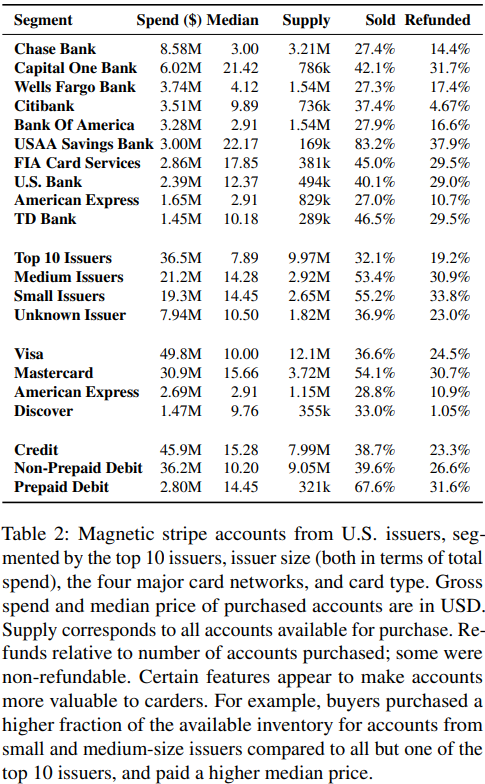

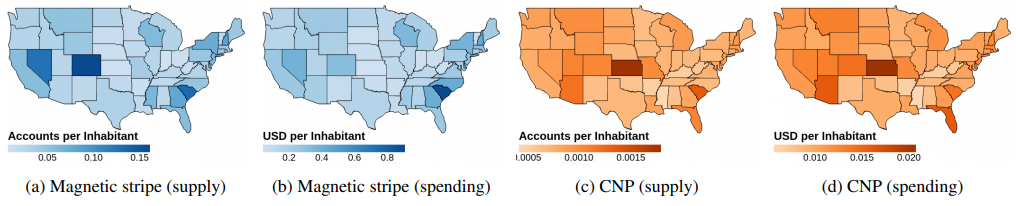

More recently, researchers at Cyber R&D Labs published a paper detailing how they tested 11 chip card implementations from 10 different banks in Europe and the U.S. The researchers found they could harvest data from four of them and create cloned magnetic stripe cards that were successfully used to place transactions.

There are now strong indications the same method detailed by Cyber R&D Labs is being used by point-of-sale (POS) malware to capture EMV transaction data that can then be resold and used to fabricate magnetic stripe copies of chip-based cards.

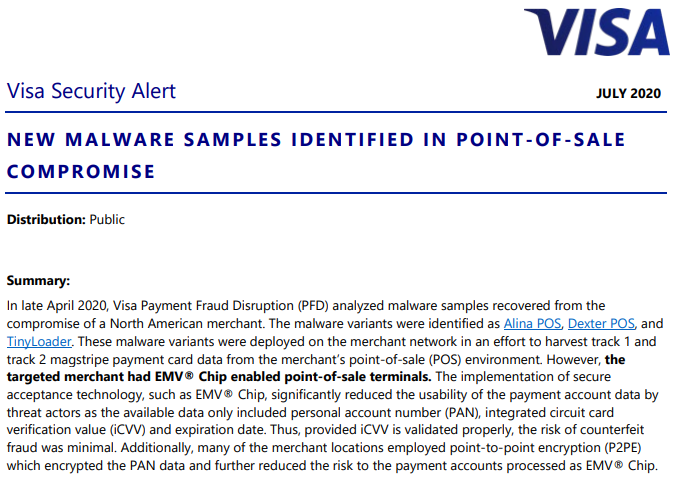

Earlier this month, the world’s largest payment card network Visa released a security alert regarding a recent merchant compromise in which known POS malware families were apparently modified to target EMV chip-enabled POS terminals.

“The implementation of secure acceptance technology, such as EMV® Chip, significantly reduced the usability of the payment account data by threat actors as the available data only included personal account number (PAN), integrated circuit card verification value (iCVV) and expiration date,” Visa wrote. “Thus, provided iCVV is validated properly, the risk of counterfeit fraud was minimal. Additionally, many of the merchant locations employed point-to-point encryption (P2PE) which encrypted the PAN data and further reduced the risk to the payment accounts processed as EMV® Chip.”

Visa did not name the merchant in question, but something similar seems to have happened at Key Food Stores Co-Operative Inc., a supermarket chain in the northeastern United States. Key Food initially disclosed a card breach in March 2020, but two weeks ago updated its advisory to clarify that EMV transaction data also was intercepted.

“The POS devices at the store locations involved were EMV enabled,” Key Food explained. “For EMV transactions at these locations, we believe only the card number and expiration date would have been found by the malware (but not the cardholder name or internal verification code).”

While Key Food’s statement may be technically accurate, it glosses over the reality that the stolen EMV data could still be used by fraudsters to create magnetic stripe versions of EMV cards presented at the compromised store registers in cases where the card-issuing bank hadn’t implemented EMV correctly. Continue reading

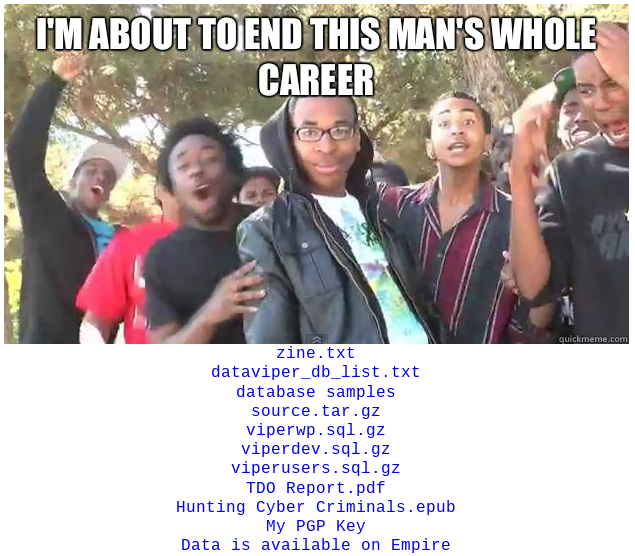

Top of the heap this month in terms of outright scariness is

Top of the heap this month in terms of outright scariness is