On Nov. 23, one of the cybercrime underground’s largest bazaars for buying and selling stolen payment card data announced the immediate availability of some four million freshly-hacked debit and credit cards. KrebsOnSecurity has learned this latest batch of cards was siphoned from four different compromised restaurant chains that are most prevalent across the midwest and eastern United States.

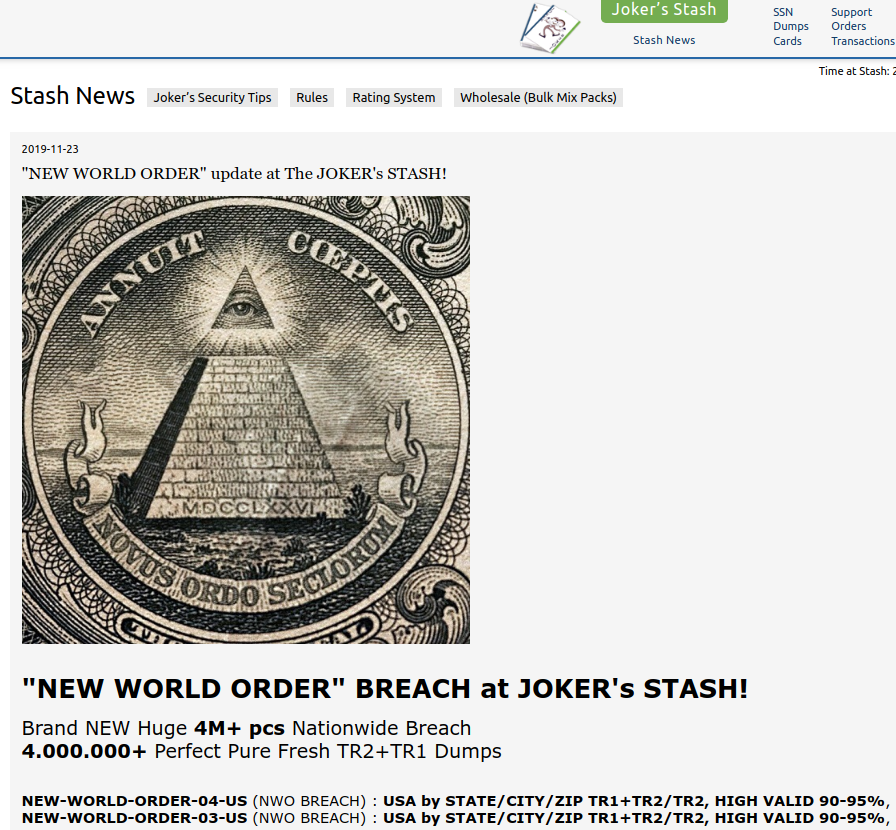

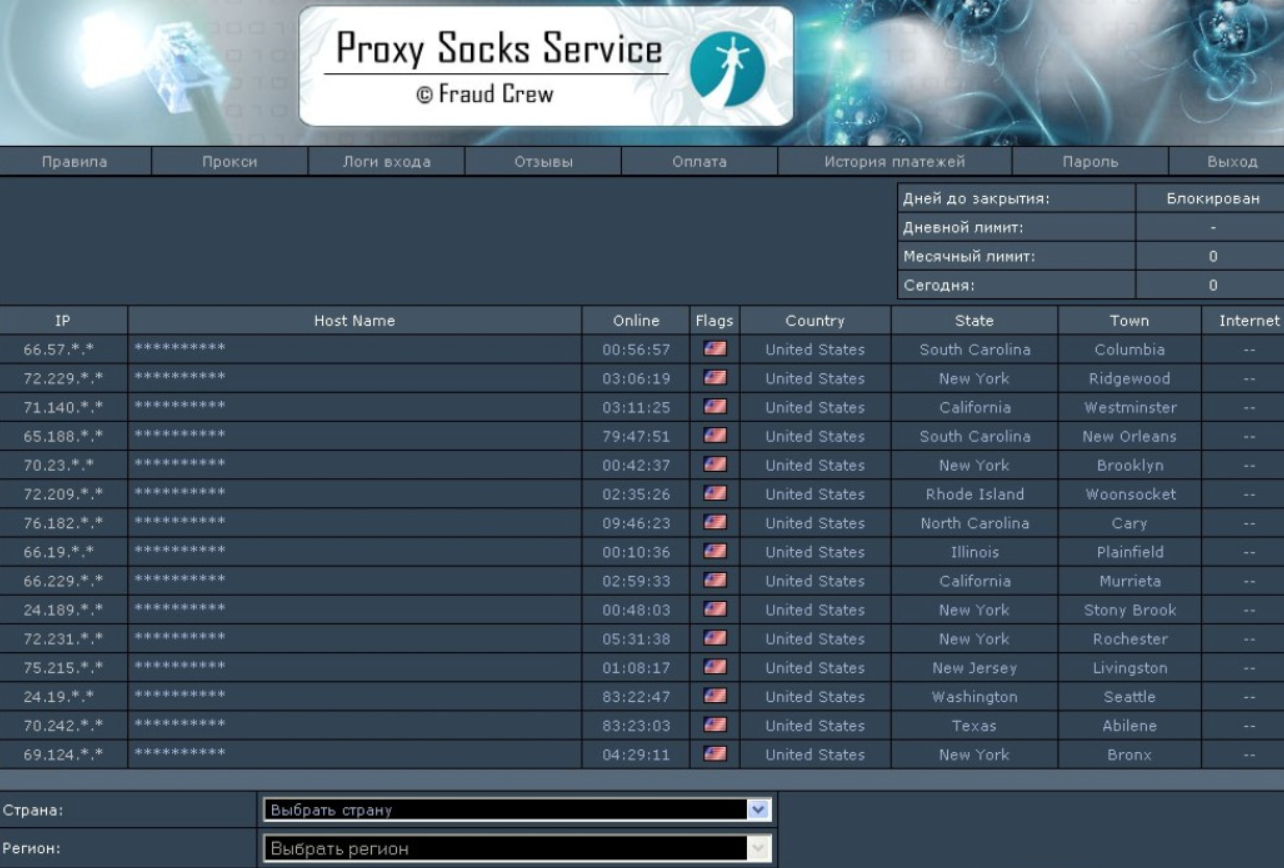

An advertisement on the cybercrime store Joker’s Stash for a new batch of ~4 million credit/debit cards stolen from four different restaurant chains across the midwest and eastern United States.

Two financial industry sources who track payment card fraud and asked to remain anonymous for this story said the four million cards were taken in breaches recently disclosed by restaurant chains Krystal, Moe’s, McAlister’s Deli and Schlotzsky’s. Krystal announced a card breach last month. The other three restaurants are all part of the same parent company and disclosed breaches in August 2019.

KrebsOnSecurity heard the same conclusion from Gemini Advisory, a New York-based fraud intelligence company.

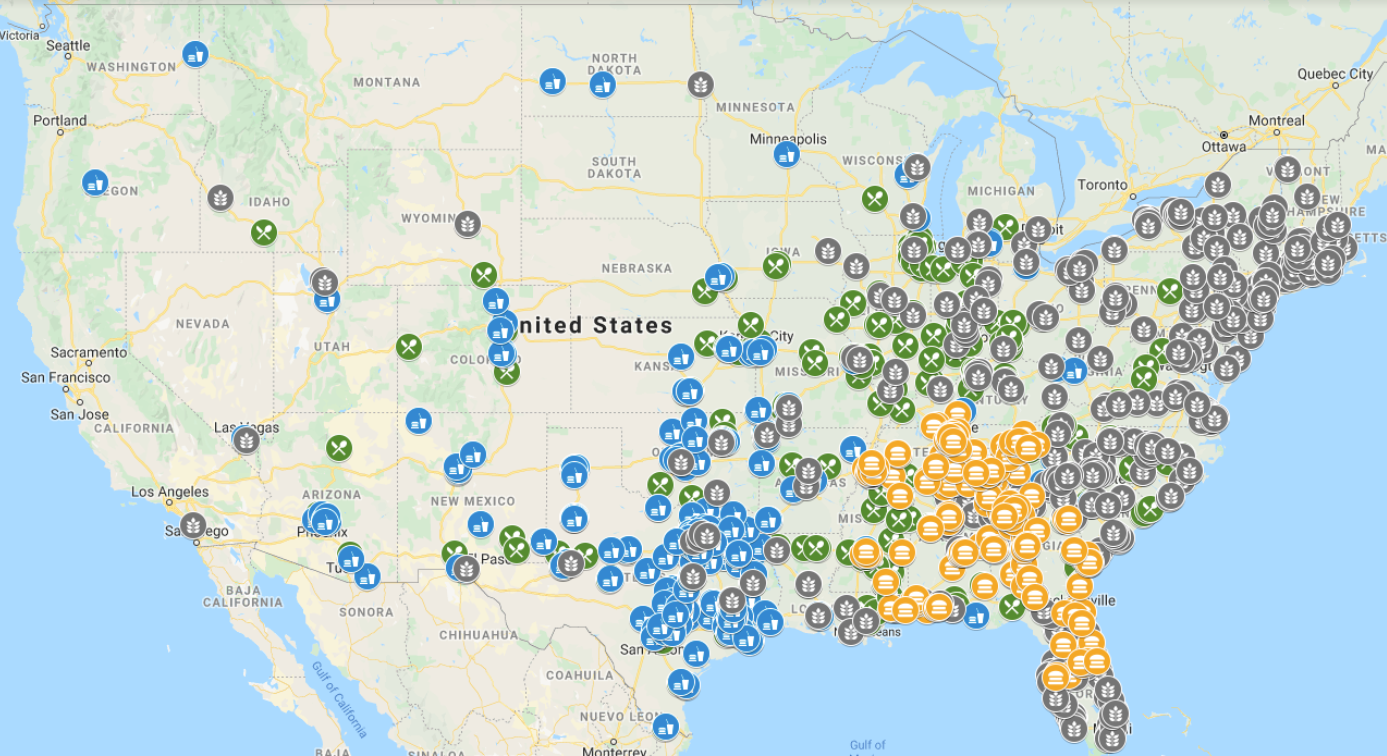

“Gemini found that the four breached restaurants, ranked from most to least affected, were Krystal, Moe’s, McAlister’s and Schlotzsky’s,” Gemini wrote in an analysis of the New World Order batch shared with this author. “Of the 1,750+ locations belonging to these restaurants, nearly 50% were breached and had customer payment card data exposed. These breached locations were concentrated in the central and eastern United States, with the highest exposure in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Alabama.”

McAlister’s (green), Schlotzsky’s (blue), Moe’s (gray), and Krystal (orange) locations across the United States. There is an additional Moe’s location in Hawaii that is not depicted. Image: Gemini Advisory.

Focus Brands (which owns Moe’s, McAlister’s, and Schlotzsky’s) was breached between April and July 2019, and publicly disclosed this on August 23. Krystal claims to have been breached between July and September 2019, and disclosed this in late October.

The stolen cards went up for sale at the infamous Joker’s Stash carding bazaar. The most recent big breach marketed on Joker’s Stash was dubbed “Solar Energy,” and included more than five million cards stolen from restaurants, fuel pumps and drive-through coffee shops operated by Hy-Vee, a supermarket chain based in Iowa.

According to Gemini, Joker’s Stash likely delayed the debut of the New World Order cards to keep from flooding the market with too much stolen card data all at once, which can have the effect of lowering prices for stolen cards across the board.

“Joker’s Stash first announced their breach on November 11, 2019 and published the data on November 22,” Gemini found. “This delay between breaches occurring as early as July and data being offered in the dark web in November appears to be an effort to avoid oversaturating the dark web market with an excess of stolen payment records.” Continue reading

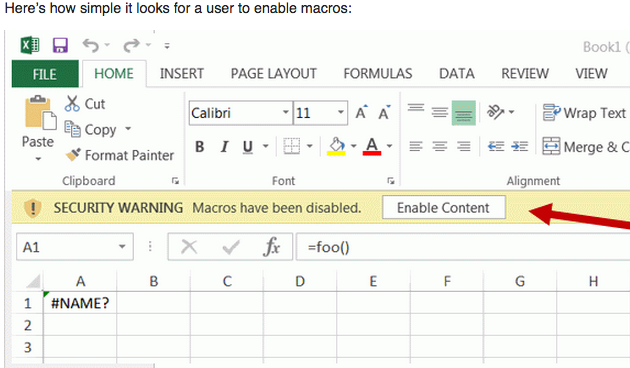

More than a dozen of the flaws tackled in this month’s release are rated “critical,” meaning they involve weaknesses that could be exploited to install malware without any action on the part of the user, except for perhaps browsing to a hacked or malicious Web site or opening a booby-trapped file attachment.

More than a dozen of the flaws tackled in this month’s release are rated “critical,” meaning they involve weaknesses that could be exploited to install malware without any action on the part of the user, except for perhaps browsing to a hacked or malicious Web site or opening a booby-trapped file attachment.