Banking industry giant NCR Corp. [NYSE: NCR] late last month took the unusual step of temporarily blocking third-party financial data aggregators Mint and QuickBooks Online from accessing Digital Insight, an online banking platform used by hundreds of financial institutions. That ban, which came in response to a series of bank account takeovers in which cybercriminals used aggregation sites to surveil and drain consumer accounts, has since been rescinded. But the incident raises fresh questions about the proper role of digital banking platforms in fighting password abuse.

On Oct. 29, KrebsOnSecurity heard from a chief security officer at a U.S.-based credit union and Digital Insight customer who said his institution just had several dozen customer accounts hacked over the previous week.

My banking source said the attackers appeared to automate the unauthorized logins, which took place over a week in several distinct 12-hour periods in which a new account was accessed every five to ten minutes.

Most concerning, the source said, was that in many cases the aggregator service did not pass through prompts sent by the credit union’s site for multi-factor authentication, meaning the attackers could access customer accounts with nothing more than a username and password.

“The weird part is sometimes the attackers are getting the multi-factor challenge, and sometimes they aren’t,” said the source, who added that he suspected a breach at Mint and/QuickBooks because NCR had just blocked the two companies from accessing bank Web sites on its platform.

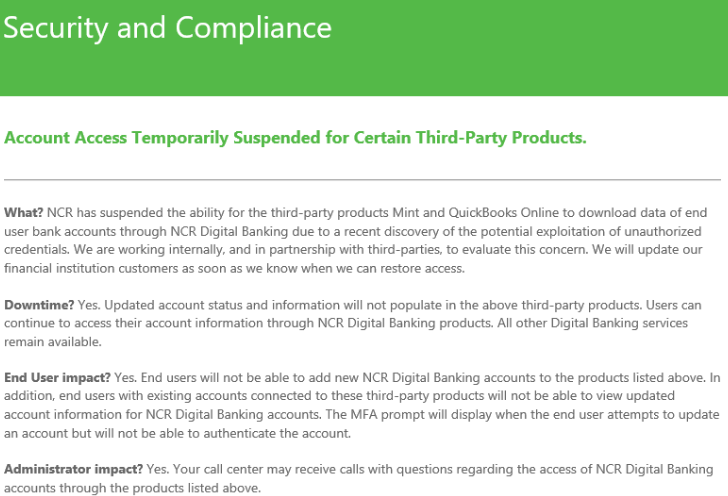

In a statement provided to KrebsOnSecurity, NCR said that on Friday, Oct. 25, the company notified Digital Insight customers “that the aggregation capabilities of certain third-party product were being temporarily suspended.”

“The notification was sent while we investigated a report involving a single user and a third-party product that aggregates bank data,” reads their statement, which was sent to customers on Oct. 29. After confirming that the incident was contained, NCR restored connectivity that is used for account aggregation. “As we noted, the criminals are getting aggressive and creative in accessing tools to access online information, NCR continues to evaluate and proactively defend against these activities.””

What were these sophisticated methods? NCR wouldn’t say, but it seems clear the hacked accounts are tied to customers re-using their online banking passwords at other sites that got hacked.

As I noted earlier this year in The Risk of Weak Online Banking Passwords, if you bank online and choose weak or re-used passwords, there’s a decent chance your account could be pilfered by cyberthieves — even if your bank offers multi-factor authentication as part of its login process. Continue reading

With more than 550 employees, Lawrence Township, N.J.-based Billtrust is a cloud-based service that lets customers view invoices, pay, or request bills via email or fax. In an email sent to customers today, Billtrust said it was consulting with law enforcement officials and with an outside security firm to determine the extent of the breach.

With more than 550 employees, Lawrence Township, N.J.-based Billtrust is a cloud-based service that lets customers view invoices, pay, or request bills via email or fax. In an email sent to customers today, Billtrust said it was consulting with law enforcement officials and with an outside security firm to determine the extent of the breach. Based in the Czech Republic, Avast bills itself as the most popular antivirus vendor on the market, with over 435 million users. In

Based in the Czech Republic, Avast bills itself as the most popular antivirus vendor on the market, with over 435 million users. In

Happily, only about 15 percent of the bugs patched this week earned Microsoft’s most dire “critical” rating. Microsoft labels flaws critical when they could be exploited by miscreants or malware to seize control over a vulnerable system without any help from the user.

Happily, only about 15 percent of the bugs patched this week earned Microsoft’s most dire “critical” rating. Microsoft labels flaws critical when they could be exploited by miscreants or malware to seize control over a vulnerable system without any help from the user.