The Internal Revenue Service has been urging tax preparation firms to step up their cybersecurity efforts this year, warning that identity thieves and hackers increasingly are targeting certified public accountants (CPAs) in a bid to siphon oodles of sensitive personal and financial data on taxpayers. This is the story of a CPA in New Jersey whose compromise by malware led to identity theft and phony tax refund requests filed on behalf of his clients.

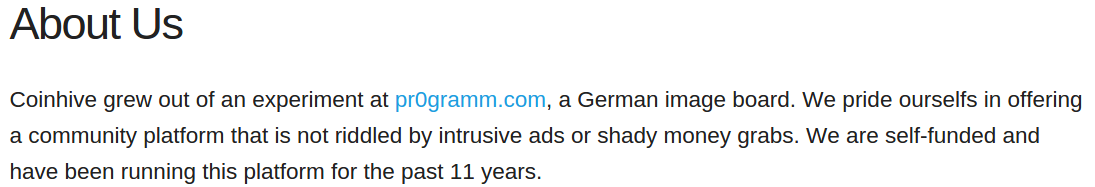

Last month, KrebsOnSecurity was alerted by security expert Alex Holden of Hold Security about a malware gang that appears to have focused on CPAs. The crooks in this case were using a Web-based keylogger that recorded every keystroke typed on the target’s machine, and periodically uploaded screenshots of whatever was being displayed on the victim’s computer screen at the time.

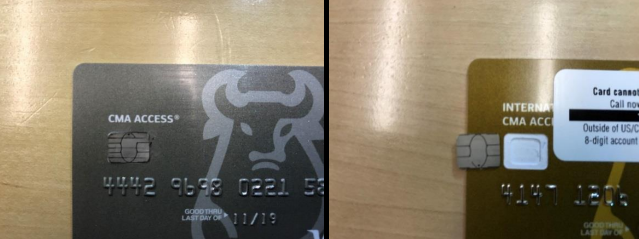

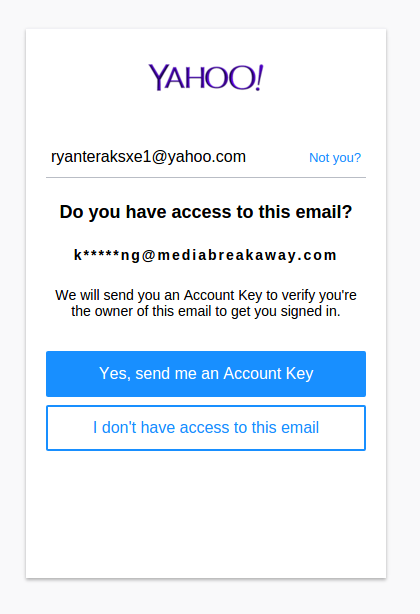

If you’ve never seen one of these keyloggers in action, viewing their output can be a bit unnerving. This particular malware is not terribly sophisticated, but nevertheless is quite effective. It not only grabs any data the victim submits into Web-based forms, but also captures any typing — including backspaces and typos as we can see in the screenshot below.

The malware records everything its victims type (including backspaces and typos), and frequently takes snapshots of the victim’s computer screen.

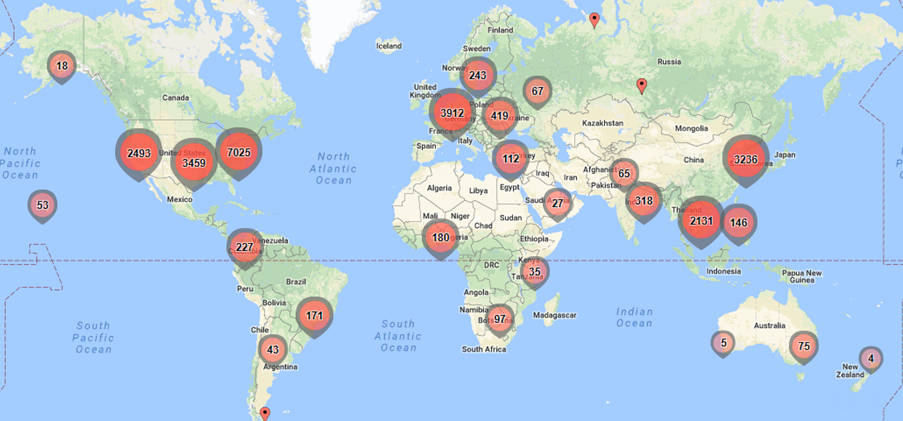

Whoever was running this scheme had all victim information uploaded to a site that was protected from data scraping by search engines, but the site itself did not require any form of authentication to view data harvested from victim PCs. Rather, the stolen information was indexed by victim and ordered by day, meaning anyone who knew the right URL could view each day’s keylogging record as one long image file.

Those records suggest that this particular CPA — “John,” a New Jersey professional whose real name will be left out of this story — likely had his computer compromised sometime in mid-March 2018 (at least, this is as far back as the keylogging records go for John).

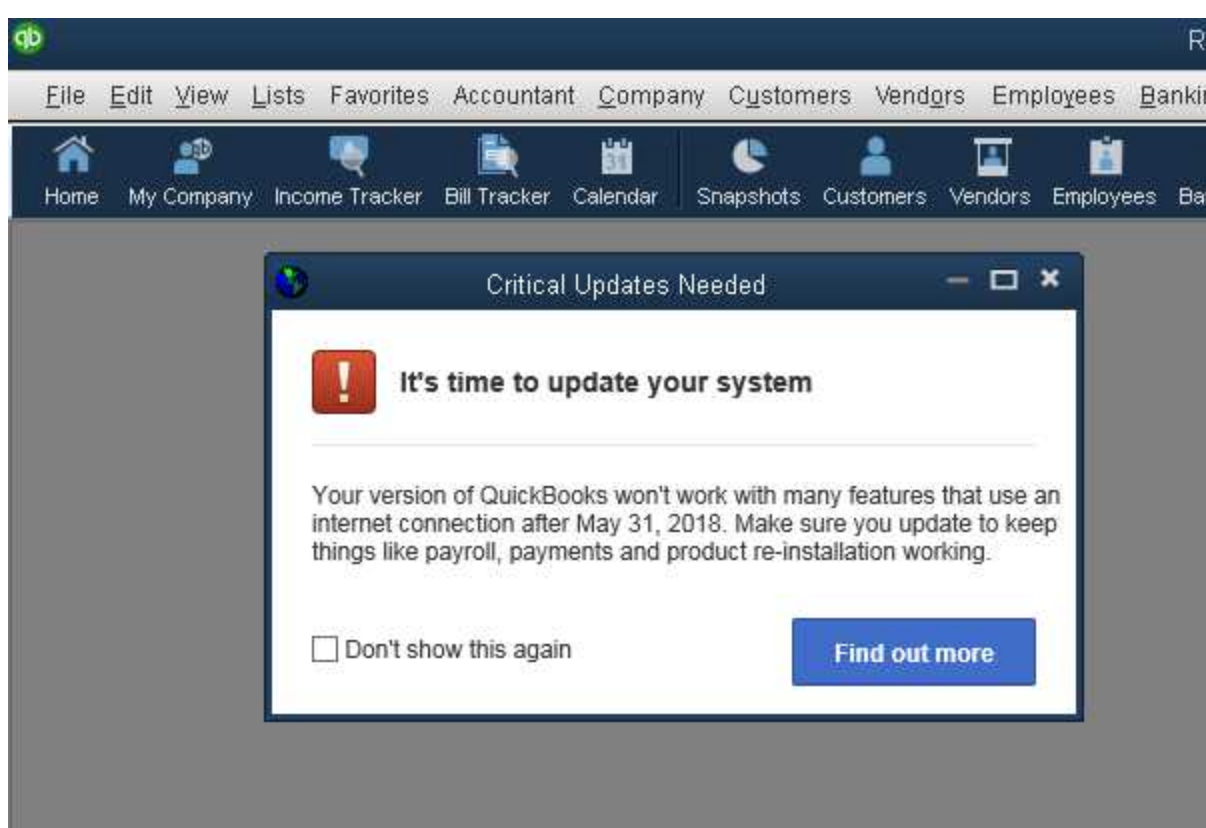

It’s also not clear exactly which method the thieves used to get malware on John’s machine. Screenshots for John’s account suggest he routinely ignored messages from Microsoft and other third party Windows programs about the need to apply critical security updates.

Messages like this one — about critical security updates available for QuickBooks — went largely ignored, according to multiple screenshots from John’s computer.

More likely, however, John’s computer was compromised by someone who sent him a booby-trapped email attachment or link. When one considers just how frequently CPAs must need to open Microsoft Office and other files submitted by clients and potential clients via email, it’s not hard to imagine how simple it might be for hackers to target and successfully compromise your average CPA.

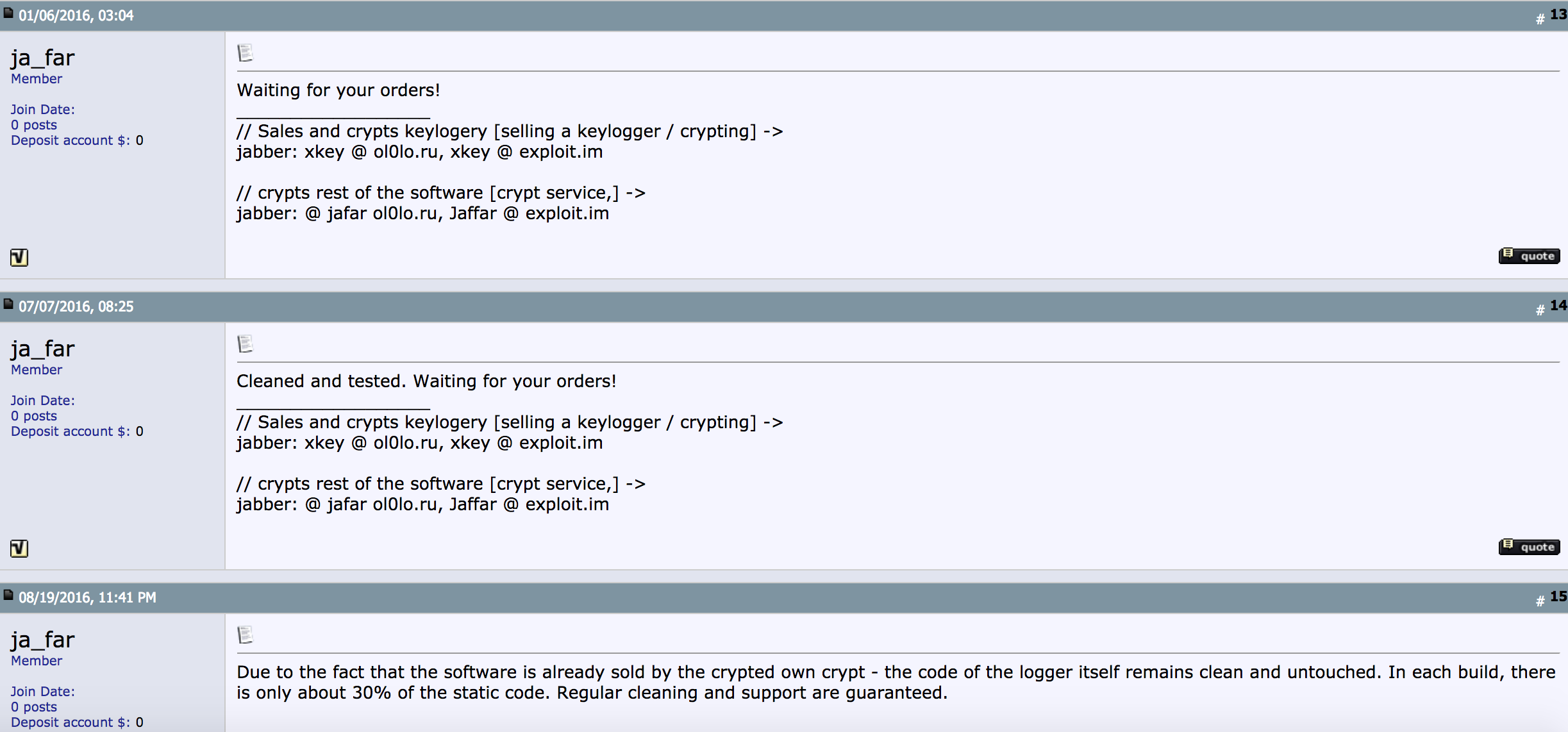

The keylogging malware itself appears to have been sold (or perhaps directly deployed) by a cybercriminal who uses the nickname ja_far. This individual markets a $50 keylogger product alongside a malware “crypting” service that guarantees his malware will be undetected by most antivirus products for a given number of days after it is used against a victim.

Ja_far’s sales threads for the keylogger used to steal tax and financial data from hundreds of John’s clients.

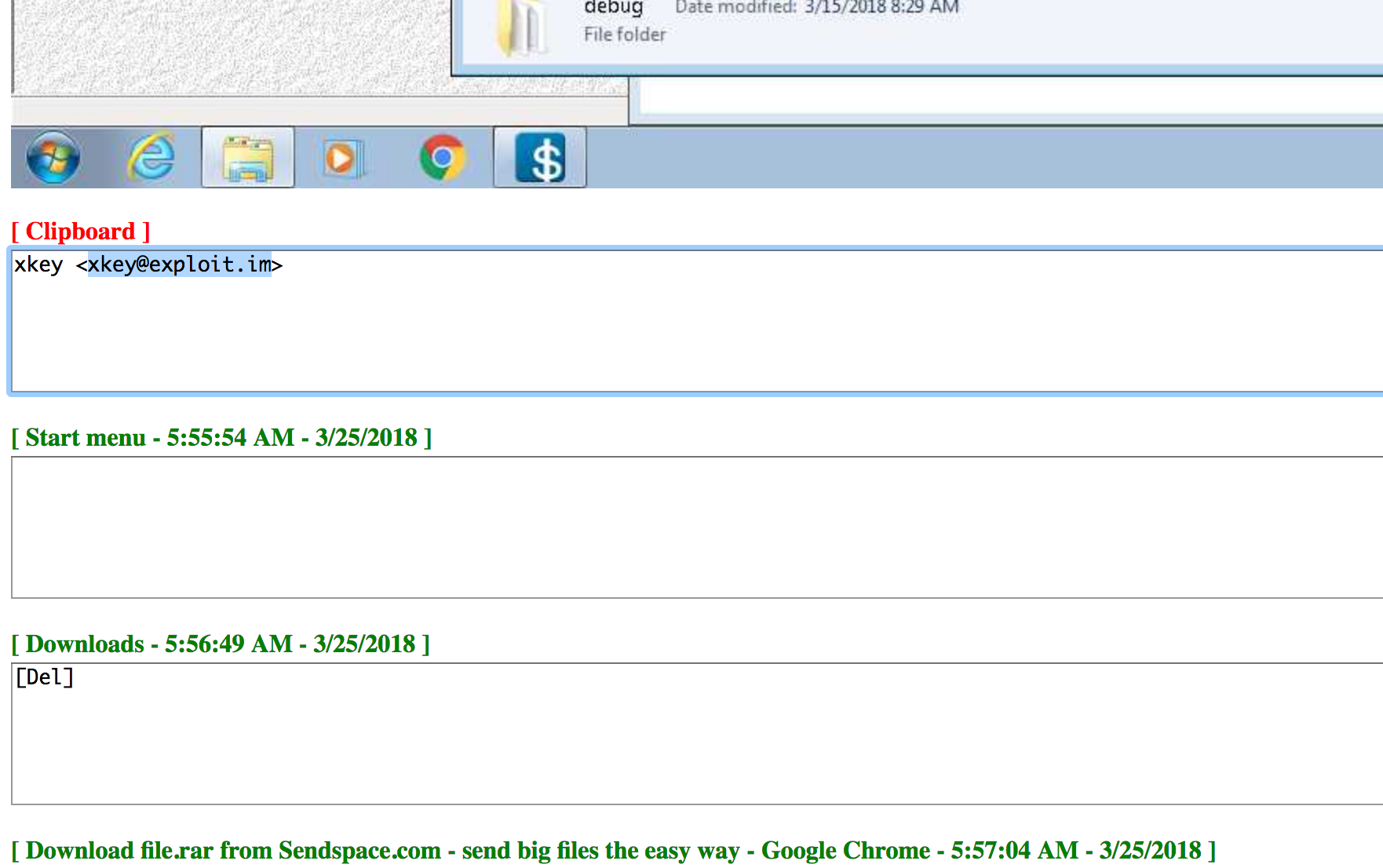

It seems likely that ja_far’s keylogger was the source of this data because at one point — early in the morning John’s time — the attacker appears to have accidentally pasted ja_far’s jabber instant messenger address into the victim’s screen instead of his own. In all likelihood, John’s assailant was seeking additional crypting services to ensure the keylogger remained undetected on John’s PC. A couple of minutes later, the intruder downloaded a file to John’s PC from file-sharing site sendspace.com.

The attacker apparently messing around on John’s computer while John was not sitting in front of the keyboard.

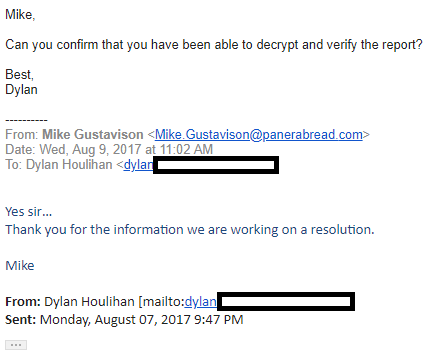

What I found remarkable about John’s situation was despite receiving notice after notice that the IRS had rejected many of his clients’ tax returns because those returns had already been filed by fraudsters, for at least two weeks John does not appear to have suspected that his compromised computer was likely the source of said fraud inflicted on his clients (or if he did, he didn’t share this notion with any of his friends or family via email).

Instead, John composed and distributed to his clients a form letter about their rejected returns, and another letter that clients could use to alert the IRS and New Jersey tax authorities of suspected identity fraud. Continue reading

The Microsoft updates impact many core Windows components, including the built-in browsers Internet Explorer and Edge, as well as Office, the Microsoft Malware Protection Engine, Microsoft Visual Studio and Microsoft Azure.

The Microsoft updates impact many core Windows components, including the built-in browsers Internet Explorer and Edge, as well as Office, the Microsoft Malware Protection Engine, Microsoft Visual Studio and Microsoft Azure.