Earlier this year, KrebsOnSecurity featured a post highlighting the most dangerous aspects of GSM-based ATM skimmers, fraud devices that let thieves steal card data from ATM users and have the purloined digits sent wirelessly via text message to the attacker’s cell phone. In that post, I explained that these mobile skimmers help fraudsters steal card data without having to return to the scene of the crime. But I thought it might be nice to hear the selling points directly from the makers of these GSM-based skimmers.

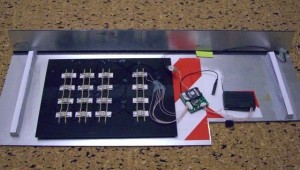

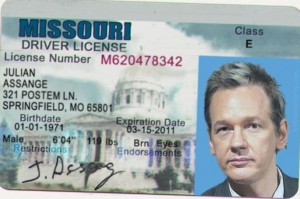

A GSM-based ATM card skimmer.

So, after locating an apparently reliable skimmer seller on an exclusive hacker forum, I chatted him up on instant message and asked for the sales pitch. This GSM skimmer vendor offered a first-hand account of why these cell-phone equipped fraud devices are safer and more efficient than less sophisticated models — that is, for the buyer at least (I have edited his sales pitch only slightly for readability and flow).

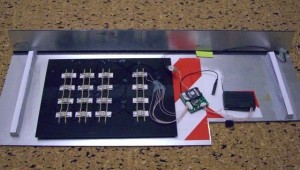

Throughout this post readers also will find several images this seller sent me of his two-part skimmer device, as well as snippets from an instructional video he ships with all sales, showing in painstaking detail how to set up and use his product. The videos are not complete. The video he sent me is about 15 minutes long. I just picked a few of the more interesting parts.

One final note: In the instruction manual below, “tracks” refer to the data stored on the magnetic stripe on the backs of all ATM (and credit/debit) cards. Our seller’s pitch begins:

“Let say we have a situation in which the equipment is established, works — for example from 9:00 a.m., and after 6 hours of work, usually it has about 25-35 tracks already on hand (on the average machine). And at cashout if the hacked ATM is in Europe, that’s approximately 20-25k Euros.

The back of a GSM-based PIN pad skimmer

So we potentially have already about 20k dollars. Also imagine that if was not GSM sending SMS and to receive tracks it would be necessary to take the equipment from ATM, and during this moment, at 15:00 there comes police and takes off the equipment.

And what now? All operation and your money f#@!&$ up? It would be shame!! Yes? And with GSM the equipment we have the following: Even if there comes police and takes off the equipment, tracks are already on your computer. That means they are already yours, and also mean this potential 20k can be cash out asap. In that case you lose only the equipment, but the earned tracks already sent. Otherwise without dumps transfer – you lose equipment, and tracks, and money.

That’s not all: There is one more important part. We had few times that the police has seen the device, and does not take it off, black jeeps stays and observe, and being replaced by each hour. But the equipment still not removed. They believe that our man will come for it. And our observers see this circus, and together with it holders go as usual, and tracks come with PINs as usual.

However have worked all the day and all the evening, and only by night the police has removed the equipment. As a result they thought to catch malicious guys, but it has turned out, that we have lost the equipment, but results have received in full. That day we got about 120 tracks with PINs. But if there was equipment that needs to be removed to receive tracks? We would earn nothing.”

Front view of a GSM-based PIN skimmer

And what about ATM skimmers that send stolen data wirelessly via Bluetooth, a communications technology that allows the thieves to hoover up the skimmer data from a few hundred meters away?

“Then after 15 minutes police would calculate auto in which people with base station and TV would sit,” says our skimmer salesman. “More shortly, in my opinion, for today it is safely possible to work only with GSM equipment.

Aside from personal safety issues, skimmer scammers also must be wary of employees or co-workers who might seek to siphon off skimmed data for themselves. Our man explains:

“Consider this scenario: You have employed people who will install the equipment. For you it is important that they do not steal tracks. In the case of skimmer equipment that does not transfer dumps, the worker has full control over receiving of tracks.

Well, you have the right to be doing work in another country. 🙂 And so, people will always swear fidelity and honesty. This normal behavior of the person, but do not forget with whom you work. And in our situation people have no tracks in hands and have no PINs in hands. They can count quantity of holders which has passed during work and that’s all. And it means that your workers cannot steal any track.

Continue reading →

The hacks were detailed in the second edition of “Owned and Exposed,” an ezine whose first edition in May included the internal database and thousands of stolen credit card numbers and passwords from Carders.cc. The Christmas version of the ezine doesn’t feature credit card numbers, but it does list the user names and hashed passwords of the carders.cc forum administrators. The carders.cc forum itself appears to be down at the moment.

The hacks were detailed in the second edition of “Owned and Exposed,” an ezine whose first edition in May included the internal database and thousands of stolen credit card numbers and passwords from Carders.cc. The Christmas version of the ezine doesn’t feature credit card numbers, but it does list the user names and hashed passwords of the carders.cc forum administrators. The carders.cc forum itself appears to be down at the moment.