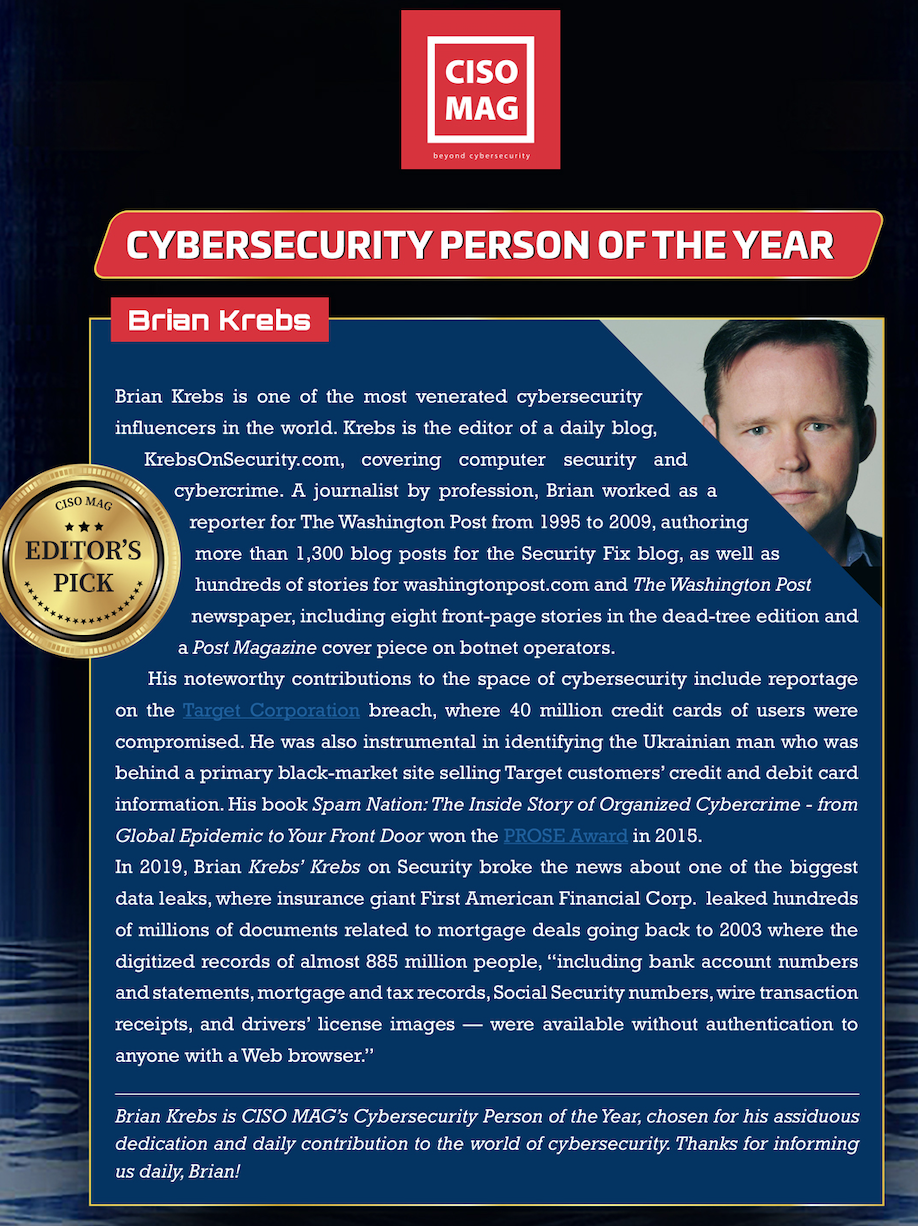

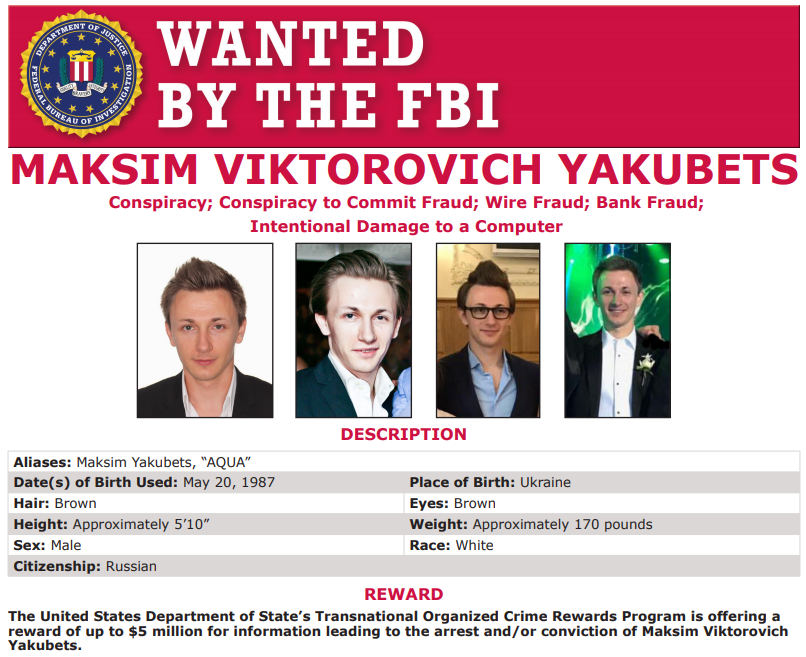

The U.S. Justice Department this month offered a $5 million bounty for information leading to the arrest and conviction of a Russian man indicted for allegedly orchestrating a vast, international cybercrime network that called itself “Evil Corp” and stole roughly $100 million from businesses and consumers. As it happens, for several years KrebsOnSecurity closely monitored the day-to-day communications and activities of the accused and his accomplices. What follows is an insider’s look at the back-end operations of this gang.

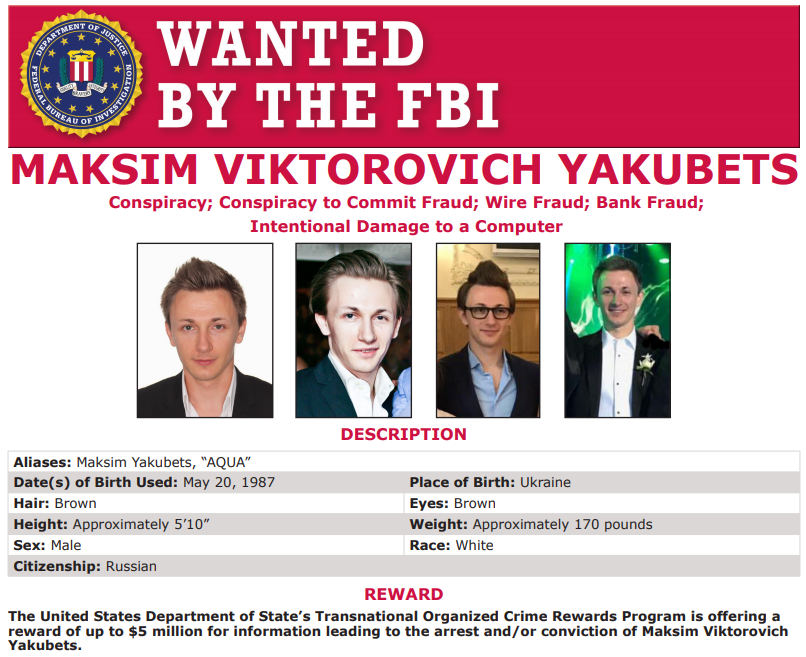

Image: FBI

The $5 million reward is being offered for 32 year-old Maksim V. Yakubets, who the government says went by the nicknames “aqua,” and “aquamo,” among others. The feds allege Aqua led an elite cybercrime ring with at least 16 others who used advanced, custom-made strains of malware known as “JabberZeus” and “Bugat” (a.k.a. “Dridex“) to steal banking credentials from employees at hundreds of small- to mid-sized companies in the United States and Europe.

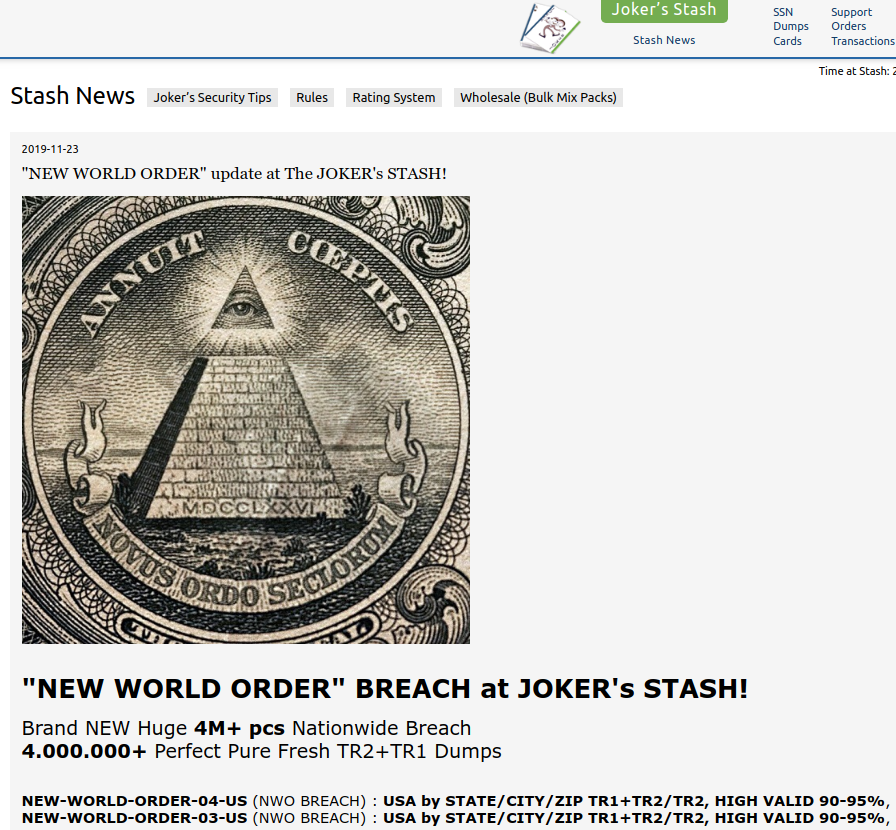

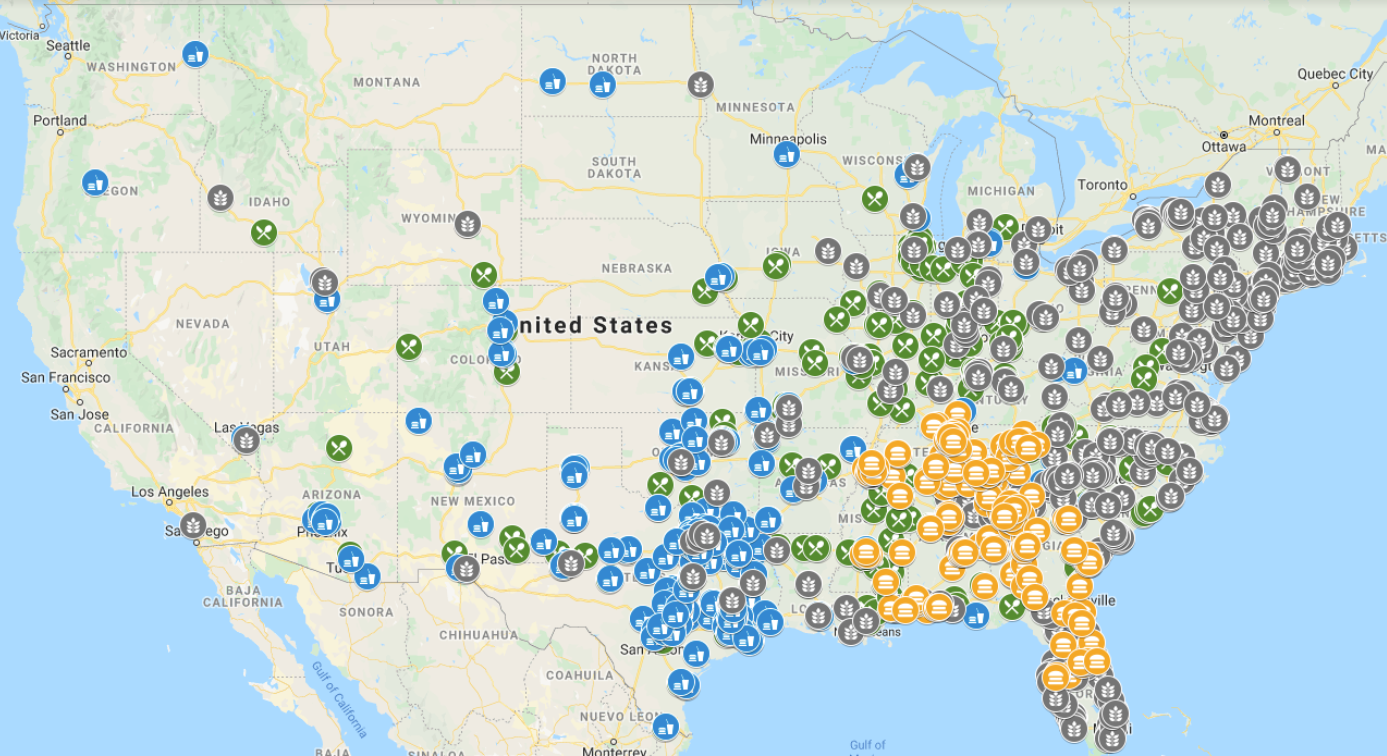

From 2009 to the present, Aqua’s primary role in the conspiracy was recruiting and managing a continuous supply of unwitting or complicit accomplices to help Evil Corp. launder money stolen from their victims and transfer funds to members of the conspiracy based in Russia, Ukraine and other parts of Eastern Europe. These accomplices, known as “money mules,” are typically recruited via work-at-home job solicitations sent out by email and to people who have submitted their resumes to job search Web sites.

Money mule recruiters tend to target people looking for part-time, remote employment, and the jobs usually involve little work other than receiving and forwarding bank transfers. People who bite on these offers sometimes receive small commissions for each successful transfer, but just as often end up getting stiffed out of a promised payday, and/or receiving a visit or threatening letter from law enforcement agencies that track such crime (more on that in a moment).

HITCHED TO A MULE

KrebsOnSecurity first encountered Aqua’s work in 2008 as a reporter for The Washington Post. A source said they’d stumbled upon a way to intercept and read the daily online chats between Aqua and several other mule recruiters and malware purveyors who were stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars weekly from hacked businesses.

The source also discovered a pattern in the naming convention and appearance of several money mule recruitment Web sites being operated by Aqua. People who responded to recruitment messages were invited to create an account at one of these sites, enter personal and bank account data (mules were told they would be processing payments for their employer’s “programmers” based in Eastern Europe) and then log in each day to check for new messages.

Each mule was given busy work or menial tasks for a few days or weeks prior to being asked to handle money transfers. I believe this was an effort to weed out unreliable money mules. After all, those who showed up late for work tended to cost the crooks a lot of money, as the victim’s bank would usually try to reverse any transfers that hadn’t already been withdrawn by the mules.

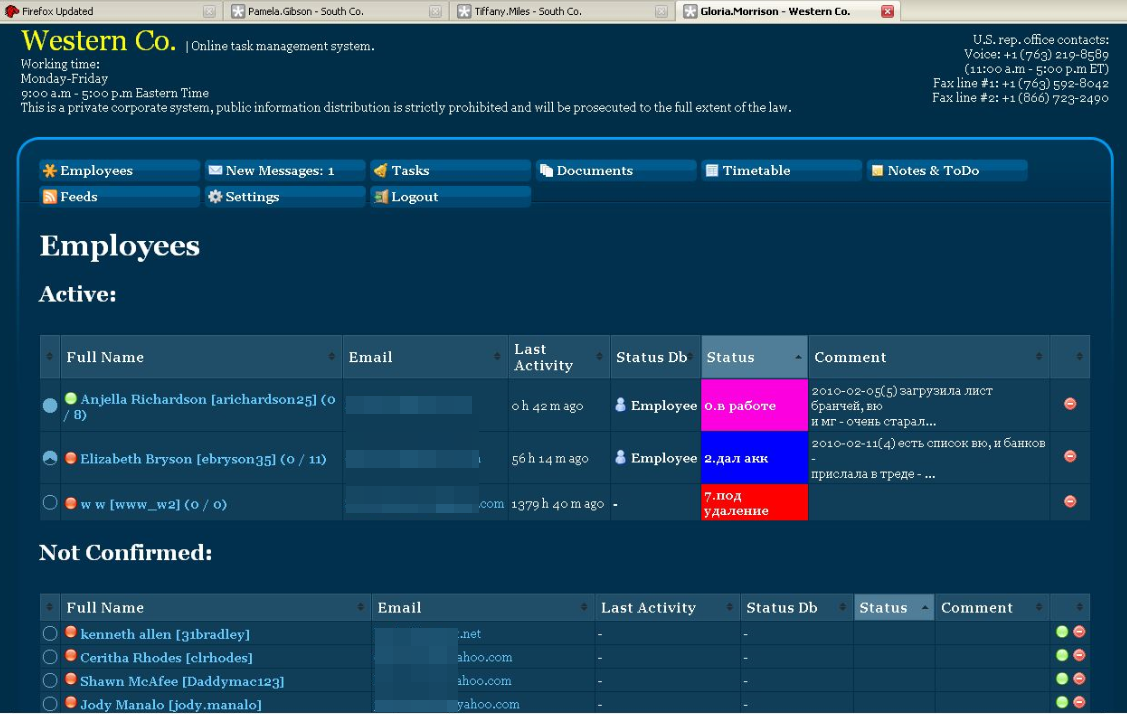

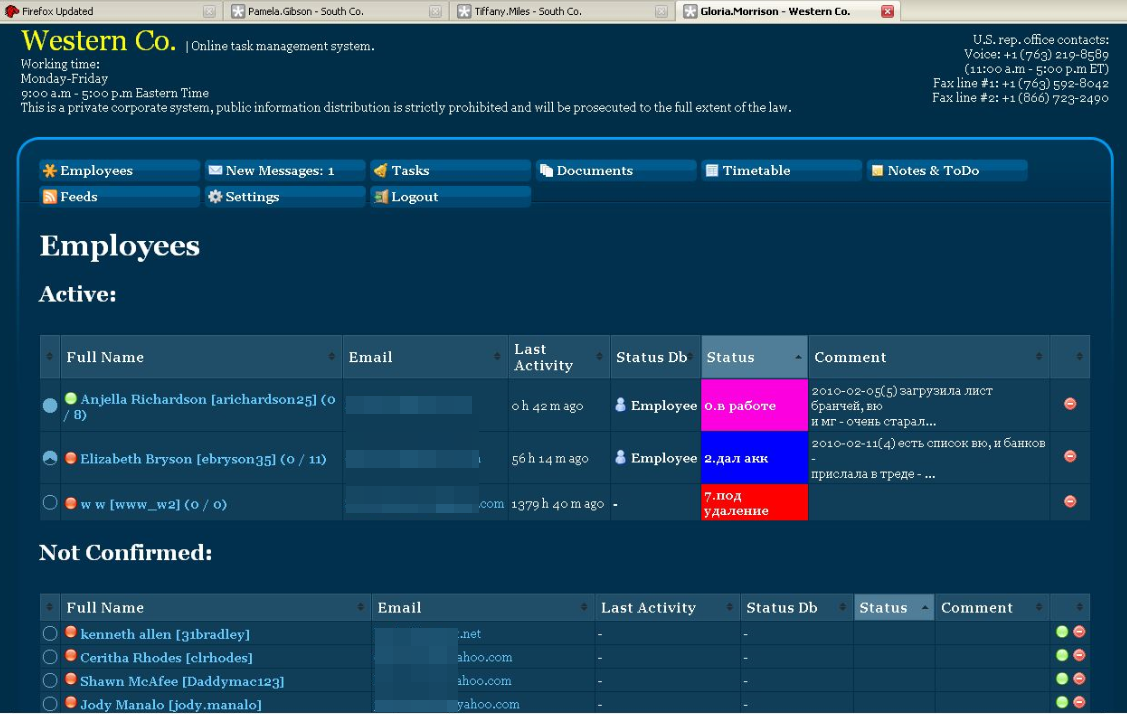

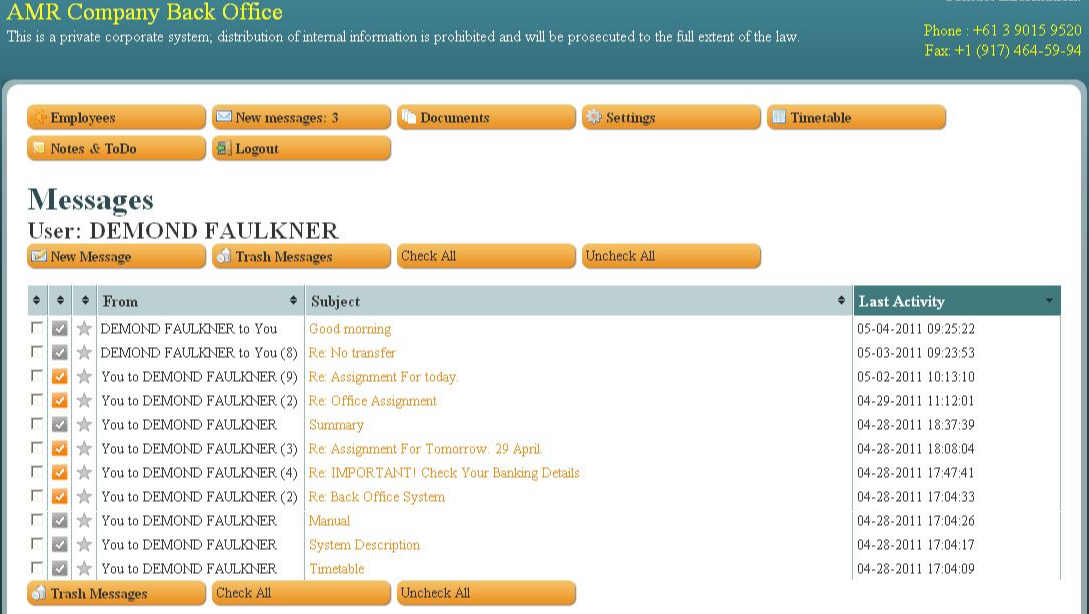

One of several sites set up by Aqua and others to recruit and manage money mules.

When it came time to transfer stolen funds, the recruiters would send a message through the mule site saying something like: “Good morning [mule name here]. Our client — XYZ Corp. — is sending you some money today. Please visit your bank now and withdraw this payment in cash, and then wire the funds in equal payments — minus your commission — to these three individuals in Eastern Europe.”

Only, in every case the company mentioned as the “client” was in fact a small business whose payroll accounts they’d already hacked into.

Here’s where it got interesting. Each of these mule recruitment sites had the same security weakness: Anyone could register, and after logging in any user could view messages sent to and from all other users simply by changing a number in the browser’s address bar. As a result, it was trivial to automate the retrieval of messages sent to every money mule registered across dozens of these fake company sites.

So, each day for several years my morning routine went as follows: Make a pot of coffee; shuffle over to the computer and view the messages Aqua and his co-conspirators had sent to their money mules over the previous 12-24 hours; look up the victim company names in Google; pick up the phone to warn each that they were in the process of being robbed by the Russian Cyber Mob.

My spiel on all of these calls was more or less the same: “You probably have no idea who I am, but here’s all my contact info and what I do. Your payroll accounts have been hacked, and you’re about to lose a great deal of money. You should contact your bank immediately and have them put a hold on any pending transfers before it’s too late. Feel free to call me back afterwards if you want more information about how I know all this, but for now please just call or visit your bank.”

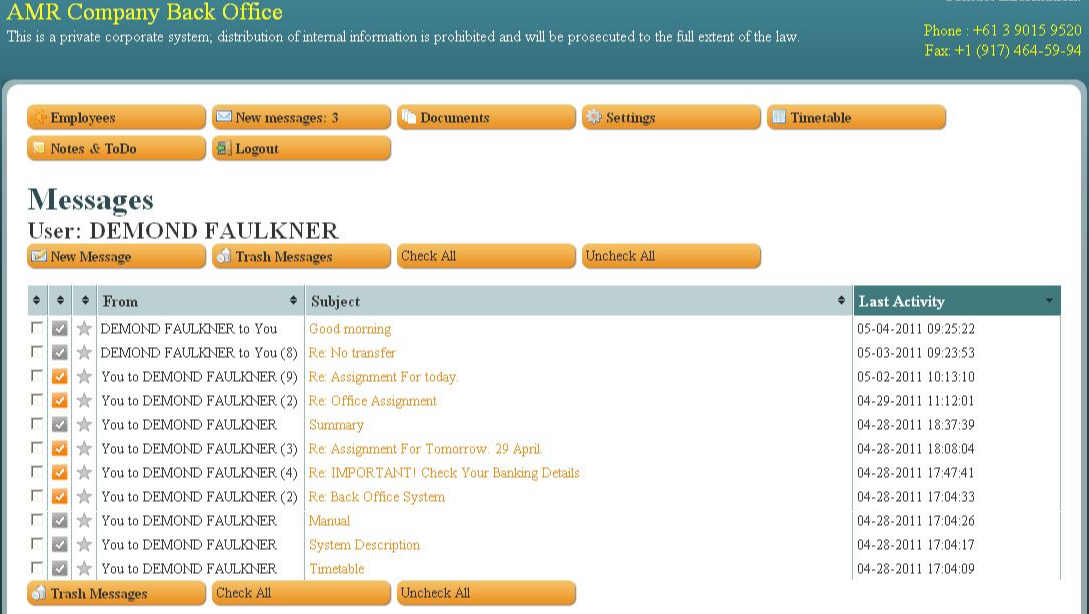

Messages to and from a money mule working for Aqua’s crew, circa May 2011.

In many instances, my call would come in just minutes or hours before an unauthorized payroll batch was processed by the victim company’s bank, and some of those notifications prevented what otherwise would have been enormous losses — often several times the amount of the organization’s normal weekly payroll. At some point I stopped counting how many tens of thousands of dollars those calls saved victims, but over several years it was probably in the millions.

Just as often, the victim company would suspect that I was somehow involved in the robbery, and soon after alerting them I would receive a call from an FBI agent or from a police officer in the victim’s hometown. Those were always interesting conversations. Needless to say, the victims that spun their wheels chasing after me usually suffered far more substantial financial losses (mainly because they delayed calling their financial institution until it was too late).

Collectively, these notifications to Evil Corp.’s victims led to dozens of stories over several years about small businesses battling their financial institutions to recover their losses. I don’t believe I ever wrote about a single victim that wasn’t okay with my calling attention to their plight and to the sophistication of the threat facing other companies. Continue reading →

By nearly all accounts, the chief bugaboo this month is

By nearly all accounts, the chief bugaboo this month is