German authorities said Friday they’d arrested seven people and were investigating six more in connection with the raid of a Dark Web hosting operation that allegedly supported multiple child porn, cybercrime and drug markets with hundreds of servers buried inside a heavily fortified military bunker. Incredibly, for at least two of the men accused in the scheme, this was their second bunker-based hosting business that was raided by cops and shut down for courting and supporting illegal activity online.

The latest busted cybercrime bunker is in Traben-Trarbach, a town on the Mosel River in western Germany. The Associated Press says investigators believe the 13-acre former military facility — dubbed the “CyberBunker” by its owners and occupants — served a number of dark web sites, including: the “Wall Street Market,” a sprawling, online bazaar for drugs, hacking tools and financial-theft wares before it was taken down earlier this year; the drug portal “Cannabis Road;” and the synthetic drug market “Orange Chemicals.”

German police reportedly seized $41 million worth of funds allegedly tied to these markets, and more than 200 servers that were operating throughout the underground temperature-controlled, ventilated and closely guarded facility.

The former military bunker in Germany that housed CyberBunker 2.0 and, according to authorities, plenty of very bad web sites.

The authorities in Germany haven’t named any of the people arrested or under investigation in connection with CyberBunker’s alleged activities, but said those arrested were apprehended outside of the bunker. Still, there are clues in the details released so far, and those clues have been corroborated by sources who know two of the key men allegedly involved.

We know the owner of the bunker hosting business has been described in media reports as a 59-year-old Dutchman who allegedly set it up as a “bulletproof” hosting provider that would provide Web site hosting to any business, no matter how illegal or unsavory.

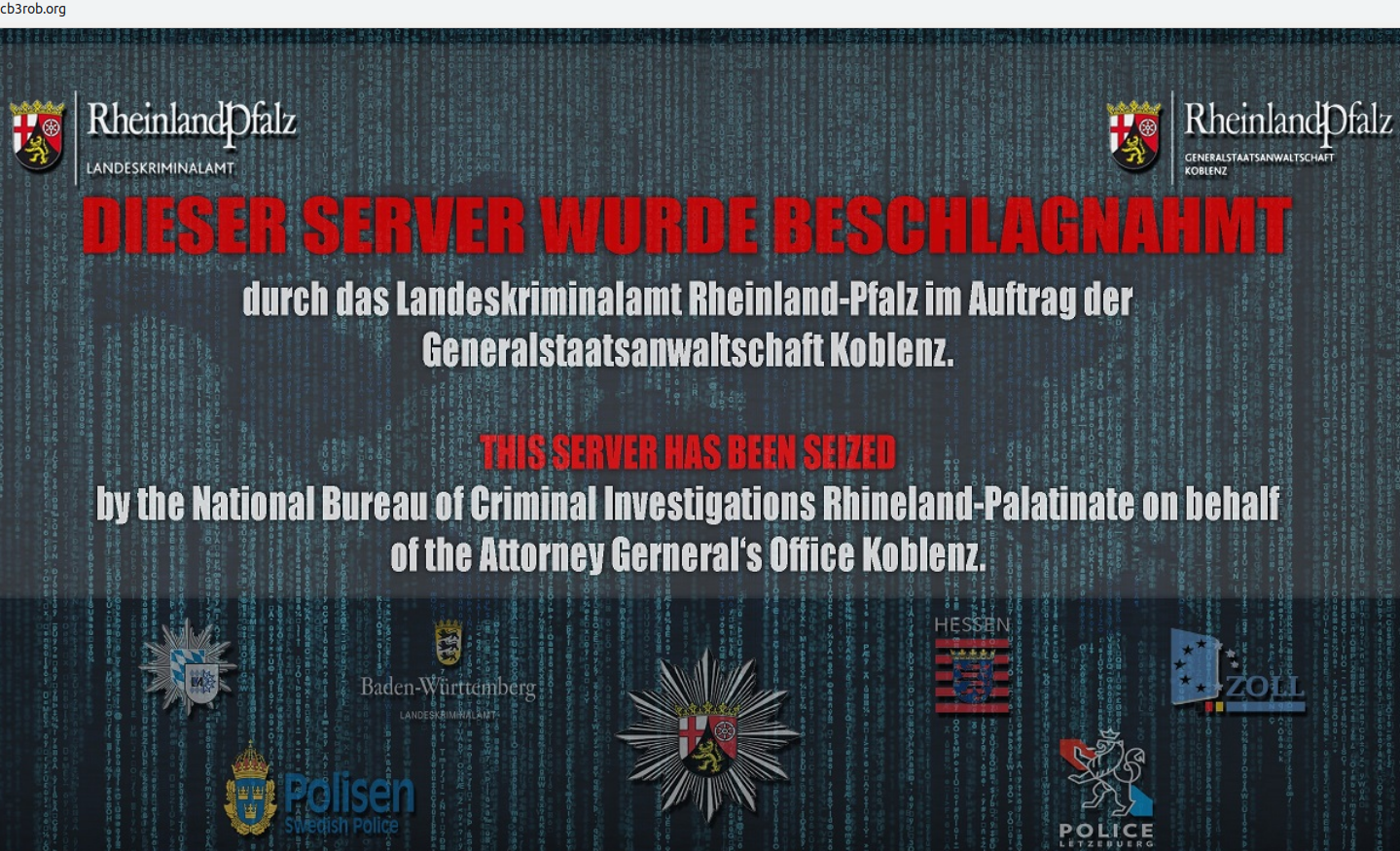

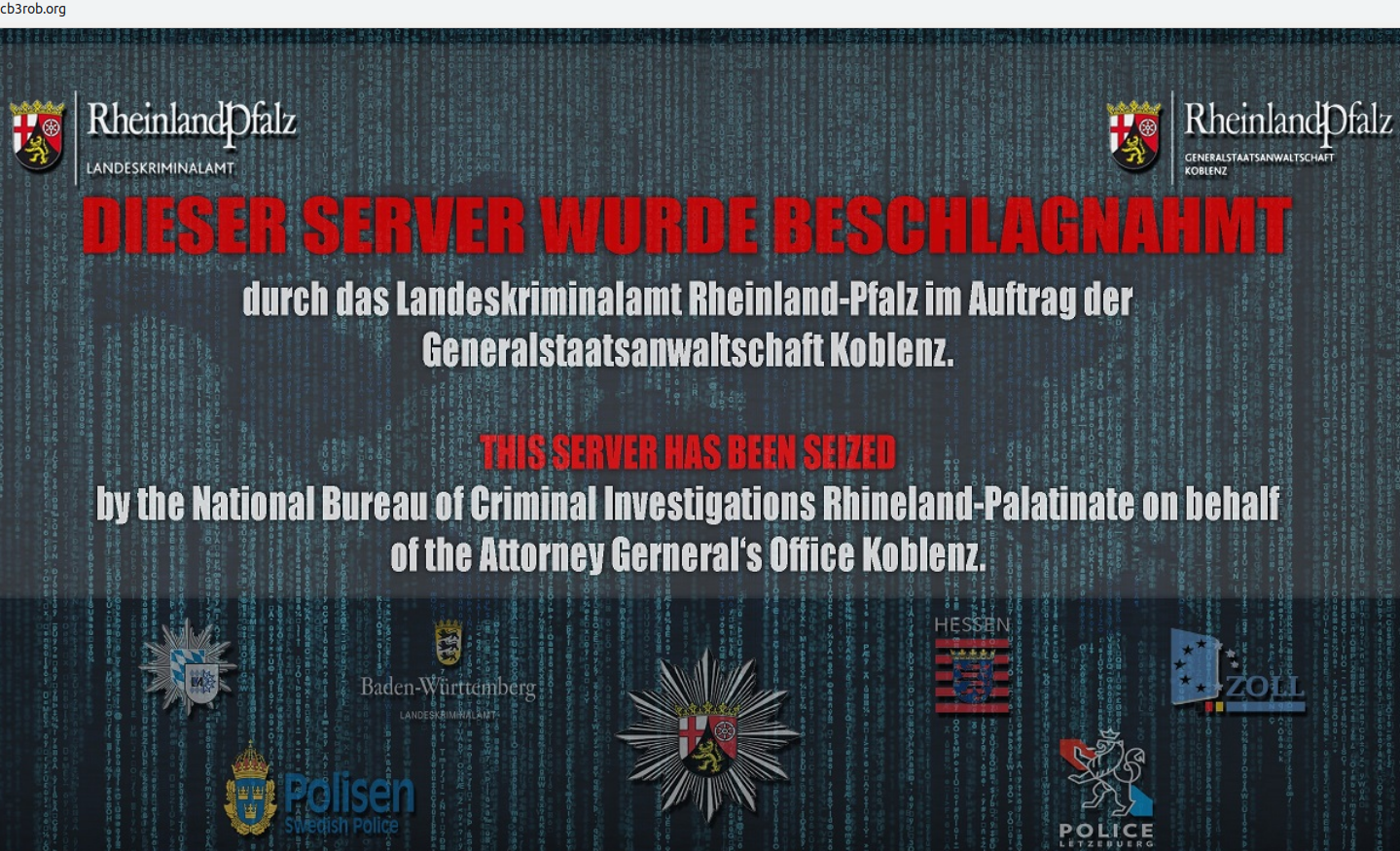

We also know the German authorities seized at least two Web site domains in the raid, including the domain for ZYZTM Research in The Netherlands (zyztm[.]com), and cb3rob[.]org.

A “seizure” placeholder page left behind by German law enforcement agents after they seized cb3rob.org, an affiliate of the the CyberBunker bulletproof hosting facility owned by convicted Dutch cybercriminal Sven Kamphuis.

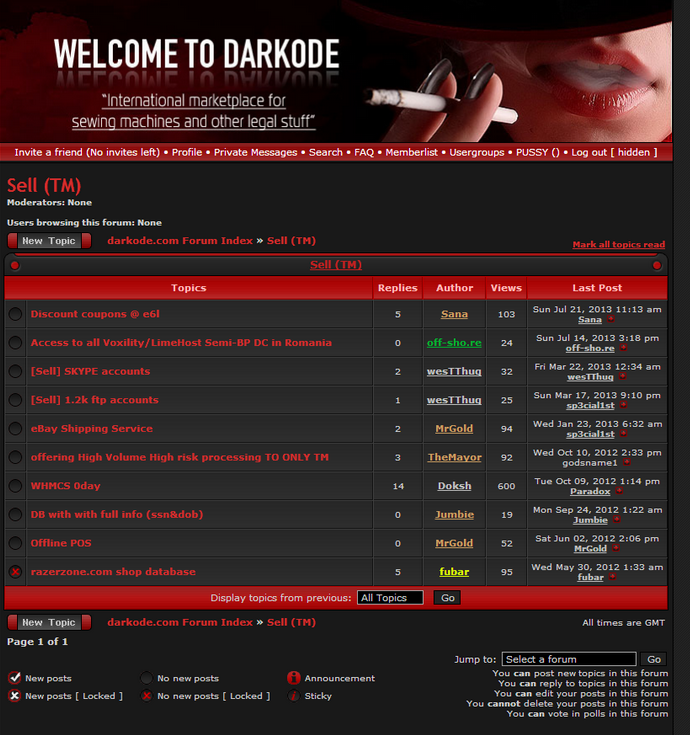

According to historic whois records maintained by Domaintools.com, Zyztm[.]com was originally registered to a Herman Johan Xennt in the Netherlands. Cb3rob[.]org was an organization hosted at CyberBunker registered to Sven Kamphuis, a self-described anarchist who was convicted several years ago for participating in a large-scale attack that briefly impaired the global Internet in some places.

Both 59-year-old Xennt and Mr. Kamphuis worked together on a previous bunker-based project — a bulletproof hosting business they sold as CyberBunker and ran out of a five-story military bunker in The Netherlands.

That’s according to Guido Blaauw, director of Disaster-Proof Solutions, a company that renovates and resells old military bunkers and underground shelters. Blaauw’s company bought the 1,800 square-meter Netherlands bunker from Mr. Xennt in 2011 for $700,000.

Guido Blaauw, in front of the original CyberBunker facility in the Netherlands, which he bought from Mr. Xennt in 2011. Image: Blaauw.

Media reports indicate that in 2002 a fire inside the CyberBunker 1.0 facility in The Netherlands summoned emergency responders, who discovered a lab hidden inside the bunker that was being used to produce the drug ecstasy/XTC.

Blaauw said nobody was ever charged for the drug lab, which was blamed on another tenant in the building. Blauuw said Xennt and others in 2003 were then denied a business license to continue operating in the bunker, and they were forced to resell servers from a different location — even though they bragged to clients for years to come about hosting their operations from an ultra-secure underground bunker.

“After the fire in 2002, there was never any data or servers stored in the bunker,” in The Netherlands, Blaauw recalled. “For 11 years they told everyone [the hosting servers where] in this ultra-secure bunker, but it was all in Amsterdam, and for 11 years they scammed all their clients.”

Firefighters investigating the source of a 2002 fire at the CyberBunker’s first military bunker in The Netherlands discovered a drug lab amid the Web servers. Image: Blaauw.

Blaauw said sometime between 2012 and 2013, Xennt purchased the bunker in Traben-Trarbach, Germany — a much more modern structure that was built in 1997. CyberBunker was reborn, and it began offering many of the same amenities and courted the same customers as CyberBunker 1.0 in The Netherlands.

“They’re known for hosting scammers, fraudsters, pedophiles, phishers, everyone,” Blaauw said. “That’s something they’ve done for ages and they’re known for it.”

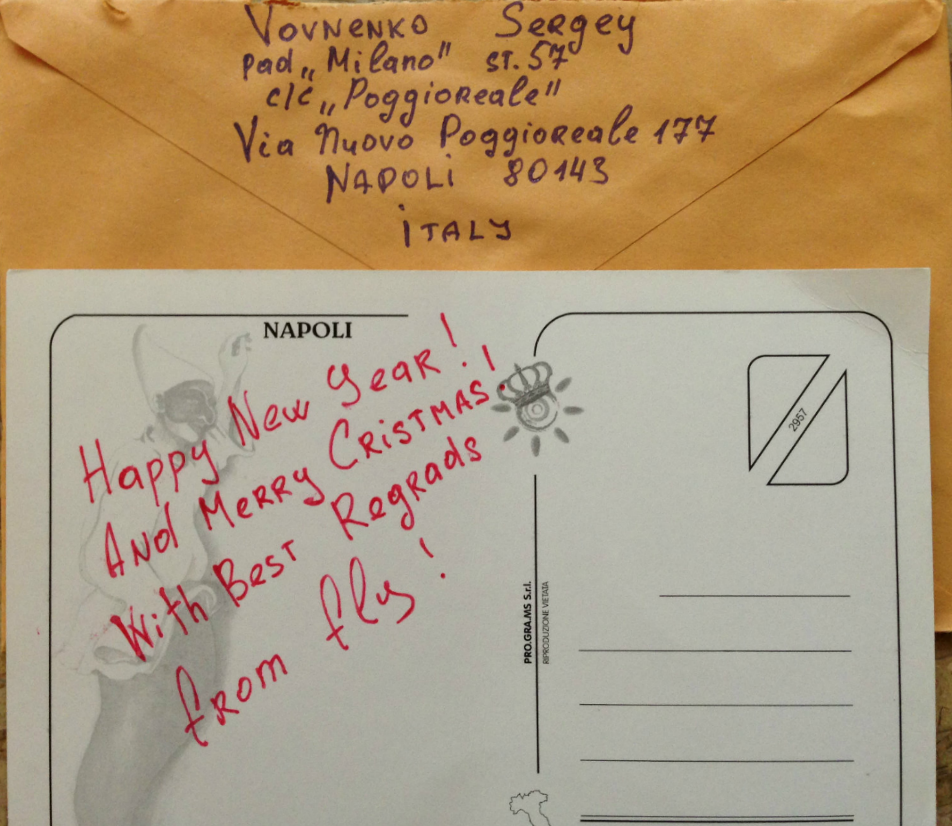

The former Facebook profile picture of Sven Olaf Kamphuis, shown here standing in front of Cyberbunker 1.0 in The Netherlands.

Continue reading →

Two of the bugs quashed in this month’s patch batch (

Two of the bugs quashed in this month’s patch batch (